Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

I’m in the middle of a series about the impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on my families. Jesse James Bryan, first cousin to my paternal grandfather Thomas Hoskins, is a series on his own!

Jesse Bryan completed his training at Camp Gordon, GA and checked in to Camp Merritt, NJ on September 9, 1918. His departure from Camp Gordon was just days before the flu took hold there.

“About September 15, 1918, the increase in influenza assumed epidemic proportions and steadily increased to its height during the early part of October. Camp Gordon seems to have been particularly fortunate in the relatively low mortality which attended this epidemic, only 138 fatal cases of pneumonia resulting from the respiratory complications of influenza.” US Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History

Although I have no letters or knowledge of Jesse’s experience, a look at photos and the writings of others may shed some light on his experience. Click on images and clippings to enlarge and zoom in.

Troops arrived in New Jersey from training camps by train. The photos below were taken at the train station near Camp Merritt a couple of weeks before Jesse’s arrival.

Troop train on Erie RR arrives at Cresskill RR Station Jul 25. 1918

NARA111-SC-15584-ac

Source of Photograph: National Archives RG 111

Soldier’s gear was unloaded

Baggage being off loaded at Cresskill Station on to trucks for delivery at Camp Merritt Jul 24, 1918 NARA111-SC-15577-ac

Source of Photograph: National Archives RG 111

and the men began their march to Camp Merritt.

Troops leaving Erie Station at Cresskill, NJ on the way to Camp Merritt Jul 24, 1918

NARA111-SC-15579-ac

Source of Photograph: National Archives RG 111

Soldiers arriving at Cresskill NJ march to Camp Merritt Jul 25, 1918

NARA111-SC-15582-ac

Source of Photograph: National Archives RG 111

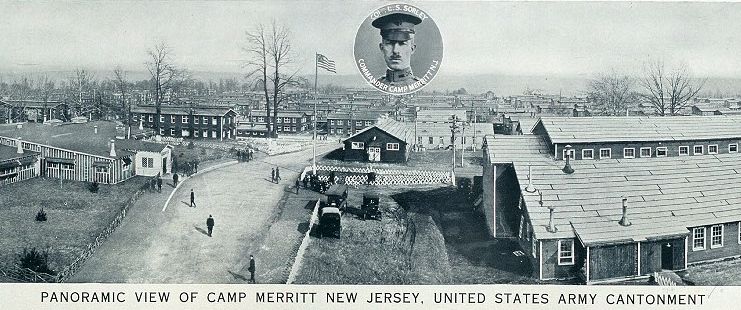

Upon arrival, we can assume there were medical rechecks and louse checks and issuing of barracks assignments. And I have no idea what else. Maybe a map, because Camp Merritt was quite large. I think of Jesse coming from a small town in Iowa, much, much smaller than either of the two camps he had been assigned to.

The information below comes from the Bergen County Historical Society website, in an article titled Remembering Camp Merritt, by John Spring.

“A total of 1,302 buildings were built to house and train 50,000 men at a time including 611 two-story wooden barracks, capable of quartering sixty-six each; 189 buildings 39 warehouses; 15 post offices 4 fire stations; 5 garages; 93 hospitals and 94 auxiliary buildings, (which included 7 tailor shops, a 24 –chair barber, a motor repair shop, a refrigerator plant, and a theater capable of seating 2,500 people).”

Mrs. Wesley Merritt, widow of the Major-General, after whom the camp was named, gave $10,000 to do something for the enlisted men. Major-General D.C. Shanks proposed using the money to adapt a building near the center of the camp into a club for the common soldier.

“The entrance lobby was furnished with ferns and poinsettias. The reading rooms were liberally supplied with wicker chairs, reading tables and lamps. The camp librarians and officers encouraged soldiers to read and allowed soldiers being shipped out to take books for reading at sea.

But the central attraction of Merritt Hall was the cafeteria with its own dishwashing machines, ice chests, a fine marble soda fountain and its own machine for carbonating water. The popularity of the food and drink dispensary is told in the almost

unbelievable figures for food and drink consumption, “four hundred and fifty dozen eggs for breakfast on an average day between 7:30 and 10:00 am”. Nine thousand apples, 400 large crullers, 900 pies and 500 gallons of ice cream were an average day’s consumption in Merritt Hall. All this was in addition to the “regular”- and supposedly adequate – food served in the mess halls every day.

Near the cafeteria was a large room with 18 tables for “pocket billiards” and other games. There were also Victrolas and coin-operated pianos for the soldiers to use in providing their own music and entertainment.

One soldier, who had complained earlier about the muddiness and flat terrain.at Fort Dix, said in a letter to his wife. “This is a fine Camp with lots of walks and nice roads. His next letter simply says, “This is the finest camp you ever saw.”

A midwesterner who later wrote a book about his experiences here in the states, on board ship and later overseas during the war, recorded this account of his time in Camp Merritt. “About three in the afternoon of May 3, (1918), we arrived at Cresskill station and at once shouldered our packs for the brief march to Camp Merritt near Tenafly, New Jersey where we were to wait for our sailing orders. We were extremely fortunate in being sent there, for Camp Merritt was probably the most comfortable camp in the United States. The barracks were built in two stories, stained on the outside,(which gave them an air of elegance quite unusual for the army), and were remarkably light and airy. The mess was excellent – But the thing which chiefly distinguished this camp was the extraordinary number, of places of recreation and the lavish way in which money had been spent to make things as cheerful and homelike as possible for the men in the last few days they were to spend in their native land. Besides the enormous structures of the Y.M.C.A. and Knights of Columbus which extended to all men in uniform the social privileges familiar to us at Oglethorpe, the general public had provided at Merritt many other agencies of relaxation and amusement quite peculiar to the camp. As Merritt was the nearest encampment to New York City, it had naturally come to be regarded as New York’s own, and a proper object of attention for all the benevolent attentions of the great metropolis. On the skirts of the camp was the Hostess House, a homelike place where men who could not get passes might meet their relatives. Within the camp was Merritt Hall, a vast,low structure, finished attractively inside, and looking something like the lobby, grill, parlors and writing rooms of a great hotel. With a library thrown in for good measure. One whole wing was in charge of the American Library Association. Here there were tables for writing, great easy chairs and settees, plants, vases of flowers, a splendid fireplace and, in low shelves about the walls, thousands of books, provided gratis for the soldier’s use. He was allowed to take them out to read in camp, and might even carry away a reasonable number with him to France”.

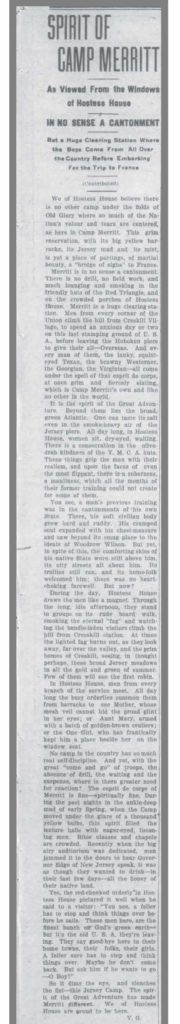

The newspaper clipping below, from March of 1918, was written by a woman who volunteered at Camp Merritt. Her writing is a bit flowery, but provides some additional glimpses into the life and feelings of those at camp.

The only thing I know for sure about Jesse’s time at Camp Merritt is that he made a trip into NYC and had a photo made in his overseas uniform. I would guess he enjoyed the good food and other amenities and perhaps spent some time reflecting on what was before him.

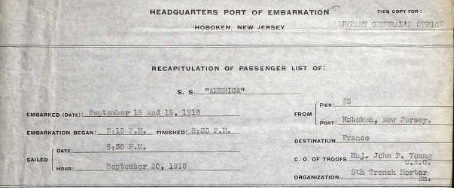

The next thing I know is that his group from Camp Gordon, and soldiers from other camps, loaded onto the transport ship America September 18-19.

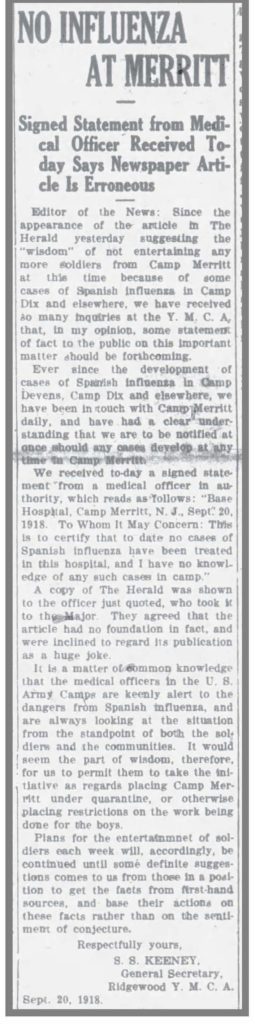

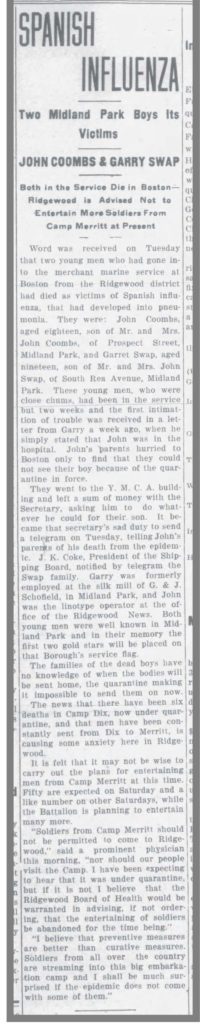

So, about nine days after his arrival at Camp Merritt, Jesse was on his way to the ship. But what was the influenza situation at Camp Merritt while Jesse was there? The Ridgewood Herald newspaper, which published the flowery description of Camp Merritt in March, published the following on September 19th, the day of or day after Jesse’s departure.

Six deaths had occurred at Camp Dix and some soldiers had been sent from Dix to Merritt. The article offered the opinion that soldiers from Camp Merritt should not be receiving the hospitality they had once enjoyed in Ridgewood due to fears of the spread of influenza.

The following day, the paper printed an article retracting that advice. The editor had received a signed statement from a medical officer at Camp Merritt stating that there had been no cases treated at the base hospital and no knowledge of any cases in the camp. Authorities at the camp called the previous notice not to entertain troops a “joke.”

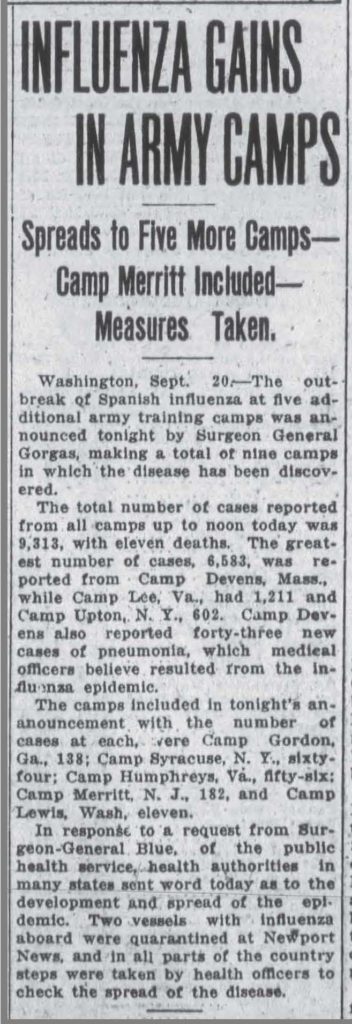

But the next day … a newspaper in Patterson, NJ printed this:

138 cases of the flu at Camp Merritt reported on September 21st.

“Pandemic influenza arrived at Camp Merritt on 16 September 1918, and it took a few days for doctors there to realize that the new flu cases were “of far greater severity” than earlier cases of flu. About a week later, many flu patients developed pneumonia. In three weeks, the base hospital expanded from one influenza ward to fifty-one influenza and pneumonia wards and brought in became sick themselves, especially nurses. Another complication was that several sick service members were transferred to Camp Merritt’s hospital from other locations, including docked ships. Dozens of enlisted soldiers detailed to assist in the wards had no medical experience. Medical officers transferred influenza patients who developed pneumonia to separate wards to isolate them from other patients. Several autopsies conducted on soldiers who died of pneumonia at Camp Merritt indicated hemorrhages in the lungs and signs of emphysema. By 1 November 1918, 265 of Camp Merritt’s 999 pneumonia patients had died, a mortality rate of just over 26 percent. The Deadliest Enemy: The U. S. Army and Influenza

Excerpts from U.S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History regarding the base hospital at Camp Merritt.

“Extra beds were placed on all the porches; the cross corridors had to be used to provide bed space, but no extra beds were at any time placed in the wards. Wires were put up not only in all wards but on porches and corridors so that sheets could be hung between all beds. In spite of the sudden influx of patients we were able to provide bed space so that proper ventilation was maintained and patients were not crowded. In these early days of the epidemic the appearance of the wards was very striding (sic). Row after row of sick men lay motionless, quite prostrated by the disease. The wards recently filled seemed like a morgue; those filled a day or two previously looked a little more cheerful with now and then a patient lifting his head or talking, while those filled three and four days before seemed more like the ordinary hospital ward. Needless to say the opportunity for observing not one patient through the various stages of the disease but an entire ward full of patients, all passing through together and always presenting a homogeneous picture, was unusual.”

“Ten officers and 50 enlisted men from Debarkation Hospital No. 2, Fox Hills, Staten Island, 21 officers and 120 men from Base Hospital No. 98, and 5 officers from the camp surgeon’s office were detailed to this hospital during the epidemic. These officers and men rendered very effective aid. With the arrival of the new personnel several cases of influenza and pneumonia developed among them almost immediately, especially among the nurses. it was very noticeable that the incidence of disease was greater in tire (sic) temporary than in the permanent personnel. This is partly explained by the new environment and the long hours under high nervous strain, and that probably the permanent staff acquired a certain immunity gradually by prolonged contact with the malady. The overwork, the care of the critically ill, especially in pneumonia wards, where the death rate was high amid the rather large number of nurses and ward attendants who succumbed to the disease had a depressing effect, and yet at no time was there evident any indication of panic. The constant supervision and care of the sick personnel was in great measure responsible for the fine esprit de corps which was maintained.”

“The number of nurses taken ill with influenza increased so rapidly that it was necessary to devote ward 37 as well as the nurses’ infirmary to them. Later ward 47, a double-decker convalescent ward, was opened for nurses. Pneumonias were treated on the porch. As soon as convalescence was established the nurses were given sick leave, many of them going to their homes.”

The Camp Merritt Memorial Monument is dedicated to the soldiers who passed through Camp Merritt, especially the 578 people – 15 officers, 558 enlisted men, four nurses and one civilian – who died at the camp due to the influenza epidemic of 1918. Their names are inscribed at the base of the monument. The memorial is located at the borders of Cresskill and Dumont in Bergen County, New Jersey at the intersection of Madison Avenue and Knickerbocker Road).

The monument, a replica of the Washington Monument, is a 66-foot tall obelisk. It features a large carved relief sculpted by Robert Ingersoll Aitken, which portrays a World War I doughboy with an eagle above it. Near the monument on a large boulder is a copper plaque designed by Katherine Lamb Tait which has a relief of the Palisades, and in the ground is a dimensional stone carving of a map of Camp Merritt. The memorial monument was dedicated on Memorial Day, May 30, 1924. General John Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force, gave the dedication address to an audience of 20,000 people.

As for Jesse Bryan, he had again escaped influenza infection.

Please visit other participants at Sepia Saturday! It is always fun and often educational.

Camp Merritt certainly was a grand facility. Thanks for sharing all the text from the US Army Military.

I originally had even more text from the military, but I decided I might be going overboard! The more I look, the more I find and sometimes I have to rein myself in.

Bad enough young men die in war, but to die even before they get there of a pandemic illness seems even more needless and sad.

It certainly does!

Even in the Civil War, my ancestor died probably from an illness before even seeing battle. The coming together in unsanitary conditions let various infections run rampant.

So many ways to die in a war. One of my ancestors also died of disease contracted during the Civil War.

This early training experience, so removed from the actual battle fronts in France, must have seemed like a kind of amusement park to most of the young soldiers. The scale of building these large camps so quickly is amazing. This was one of the great examples of how America’s industrial power was crucial to aiding our Allies against Germany. Your presentation on the Great Influenza epidemic has been very sobering to compare to our pandemic. The brave nurses of 1918 and 2020 all deserve a monument to their sacrifice and dedication.

I hadn’t thought of comparing the camp to an amusement park, but you are spot on. I just can’t fathom how people think taking precautions to control the corona virus is all about them. It puts all of us, but especially our health care workers at risk. They are brave indeed and owed so much.

Absolutely excellent research! The photographs are particularly eye-opening. When I think about the social-distancing and mask rules we have learned during the coronavirus pandemic, it is heartbreaking to see photos of the young troops packed into trains, march ranks and mess halls when the virulent 1918 influenza was spreading. It’s a miracle that Jesse avoided infection while at Camp Merritt.

There are photos of soldiers and nurses in masks and articles calling for help in making masks. They were made from gauze, so very porous, but of some help. Unfortunately too little, too late… as we seem to be on so many fronts – and no excuse for it this time around!

Hello! I grew up about 2 miles from here and had no idea about Camp Merritt. Thank you for this excellent piece. You really brought the history to life.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Thank you for leaving a comment!