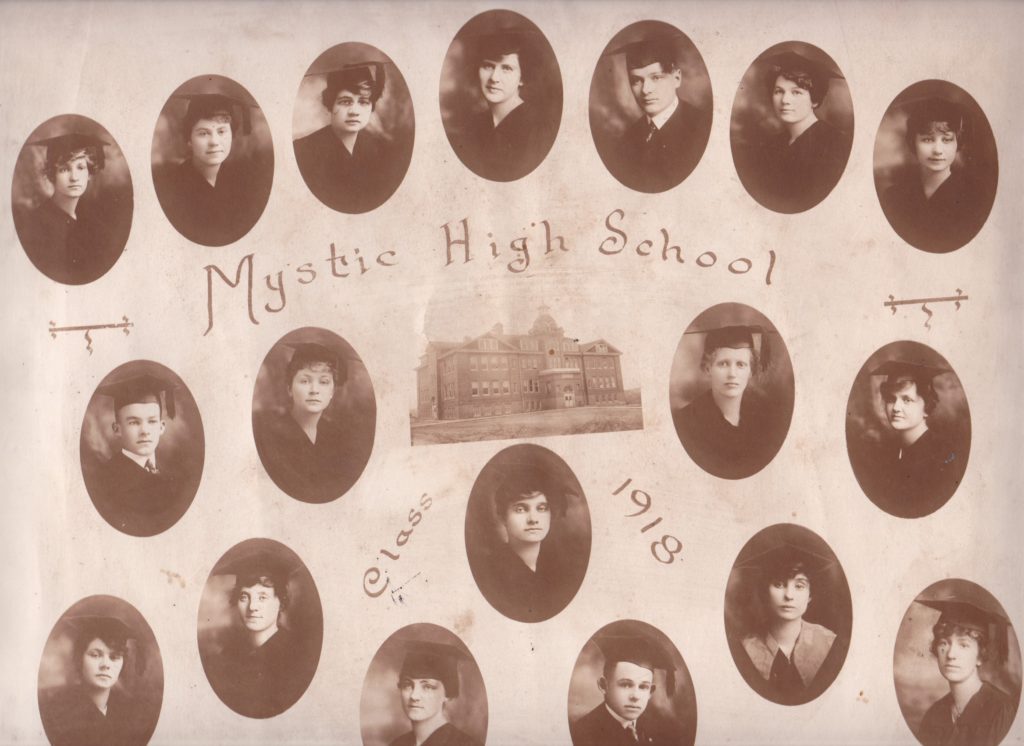

I shared a photo of my grandmother Eveline Coates’ high school graduating class in Mystic, Iowa a few weeks ago. Along with the photo and her diploma, a couple of other mementos were saved. One is the program for the Junior-Senior Banquet in honor of the graduating Seniors. It was interesting to see how World War I seemed to be the overarching theme of the festivities. I decided to take a deeper look at what her life may have been like during the 1917-1918 school year. There was a lot going on, a war and the beginning of an influenza pandemic to name the two biggies. See:

Eveline’s Senior Year: Part 1

Eveline’s Senior Year: The Draft and a Carnival

Eveline’s Senior Year: A Look Around Town

Eveline’s Senior Year: Musical Notes

I started this post a month ago and never finished it. I began with this explanation for getting behind: Part of the reason is just life – some weeks you have visitors, some weeks you have medical appointments, some weeks you are busy transcribing a record of church meetings from 1867, some weeks your husband gets COVID, some weeks you just don’t know where to begin. I’m feeling a little stuck in this series I impulsively started a couple of months ago. I have spent countless hours reading and clipping old newspaper articles and then having to find them on my computer and properly name them so I can find them again! Not to mention going down unrelated rabbit holes. I seem to have gone about this in the most time-consuming way possible. Perhaps some kind of a plan would have been wise…

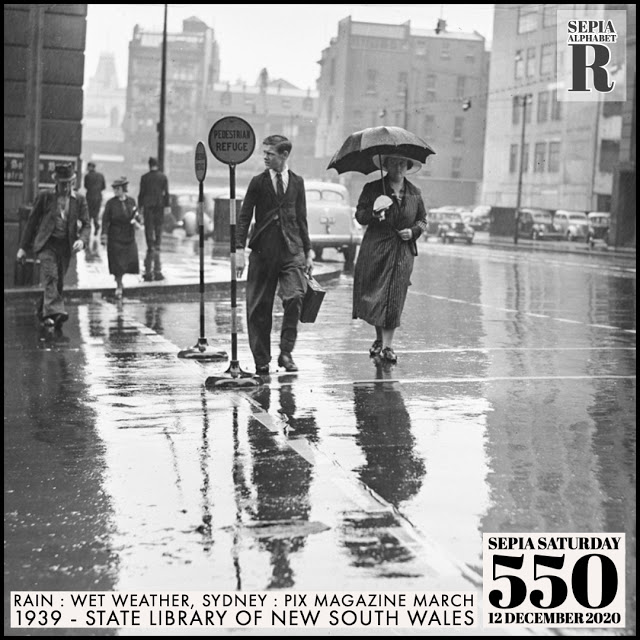

As you can see, the prompt photo was for the weekend of May 21st! Today is June 18th. I did “off-topic” posts the last two weeks, but today I’ll finish what I started back in May. No more waiting!

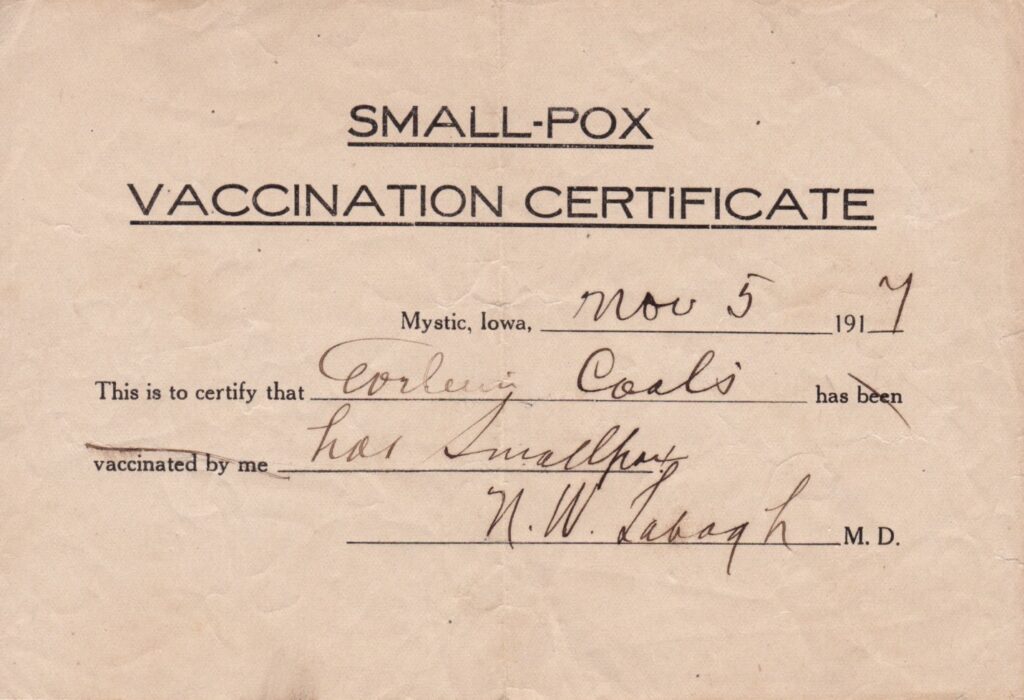

As I was going through some of my grandmother’s papers, I came across a certificate of smallpox vaccination. Eveline had the disease and not the vaccine. It is signed by Dr. Labagh, the family doctor and dated Nov. 5, 1917.

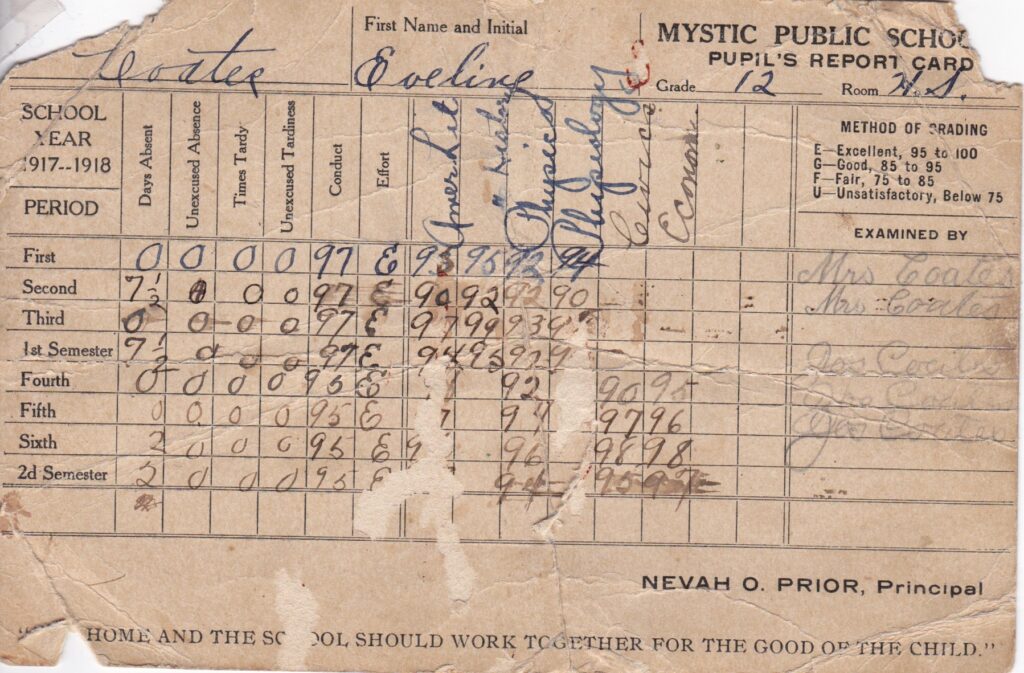

Evellne’s report card shows that she was absent for 7.5 days during the second grading period of the fall semester of her senior year (1917). I don’t know the exact dates of each grading period, but the Nov. 5th date looks like it matches up well. Those 7.5 days were the only days she was absent during the fall semester. I suppose she went to school and started feeling poorly and went home. She saw the doctor on Nov. 5th and he diagnosed her illness as smallpox. She missed about a week and a half of school, add in a weekend or two, so it looks like she was under the weather for about two weeks.

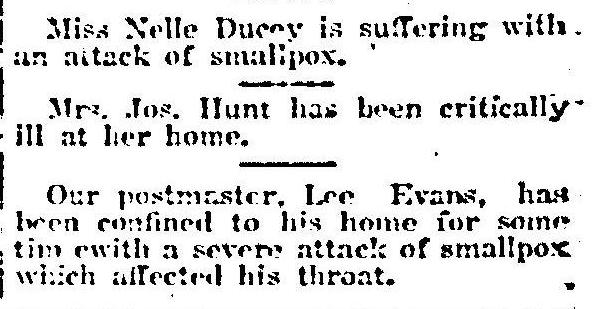

The local newspapers are filled with little notes of who has the disease and what homes are under quarantine during the timeframe of Eveline’s senior year. Miss Nelle Ducey and the postmaster, Lee Evans. had smallpox around the same time Eveline did. Her name, however, did not make it into the paper. Note: Centerville was the county seat and had the prominent newspaper. There were columns devoted to news from the various smaller towns, including Eveline’s home town, Mystic.

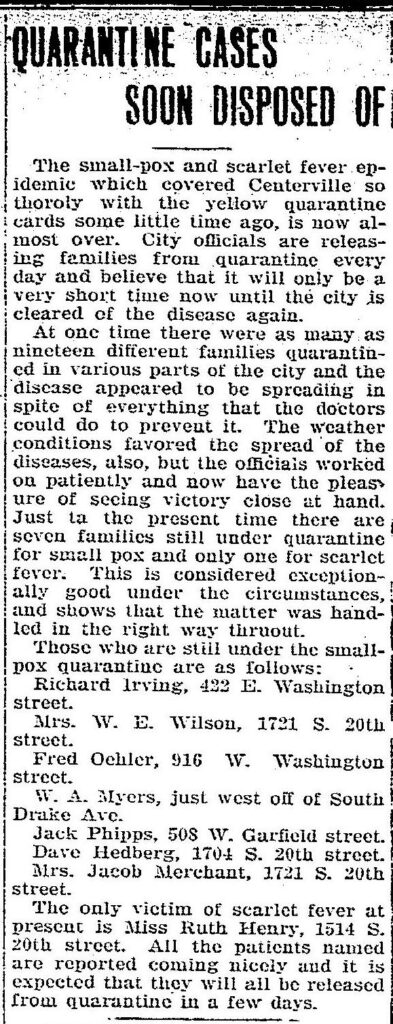

I was unaware of yellow quarantine cards until I read this article from May 1917 (just as school was about over for Eveline’s Junior year) concerning smallpox in the county seat, Centerville, Iowa.

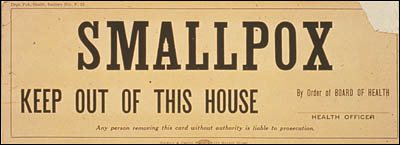

Maybe the signs in Centerville looked something like this.

Although I can’t find the source now, someone in the county was arrested for entering a house that was under quarantine. Just disregarded that yellow sign …

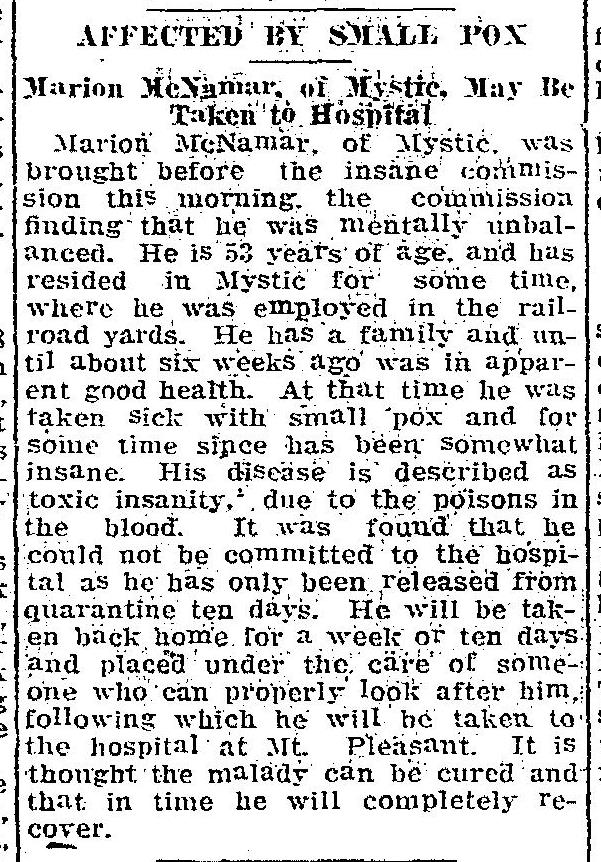

It seems that most of the smallpox cases in the area during 1917-1918 did not result in death. Perhaps the less severe strain, variola minor, was going around. One man in Mystic, however, was reported to have a rare effect from the disease.

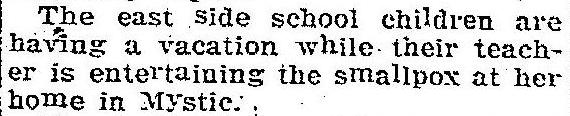

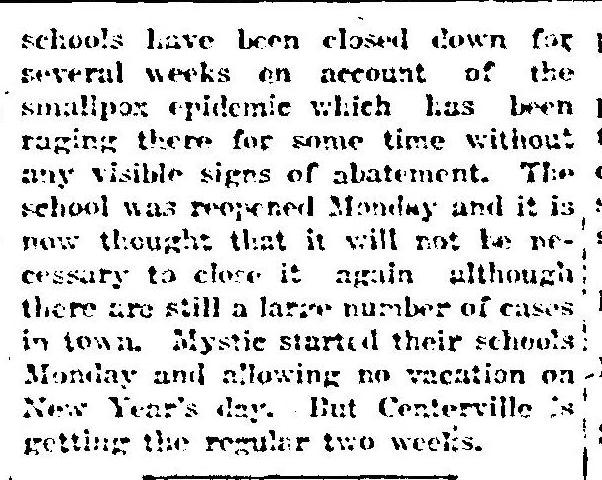

Schools were sometimes closed due to smallpox. East Side school had to close because the teacher was “entertaining” in October.

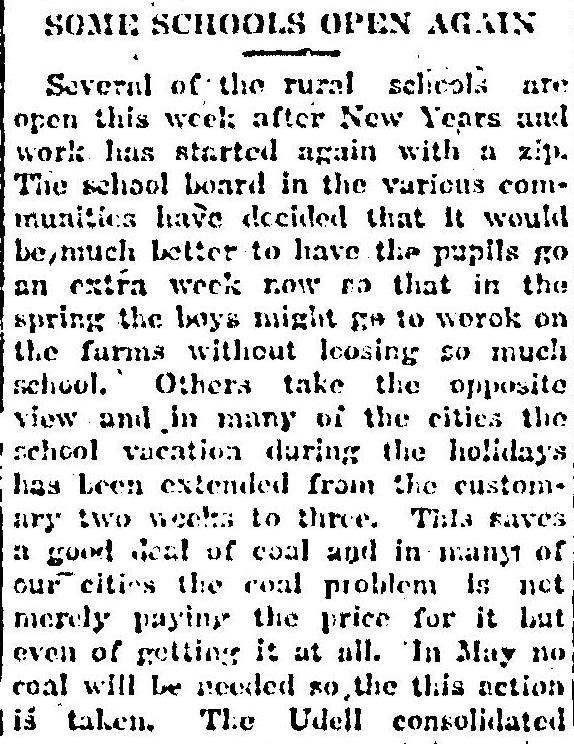

School districts in the county had to decide how to handle the winter break due to the number of cases of smallpox and days missed due to closures. Would it be better to make up lost time now so that the boys are out in time for farm work in May or remain closed for the usual holiday break (or longer) to save on coal that won’t be needed in May? Eveline’s high school re-opened on Monday, December 31, and there was no day off for the New Year.

Eveline’s doctor spoke on the subject of small pox at the Appanoose County Medical Society meeting in April 1918, which was expected to be well attended.

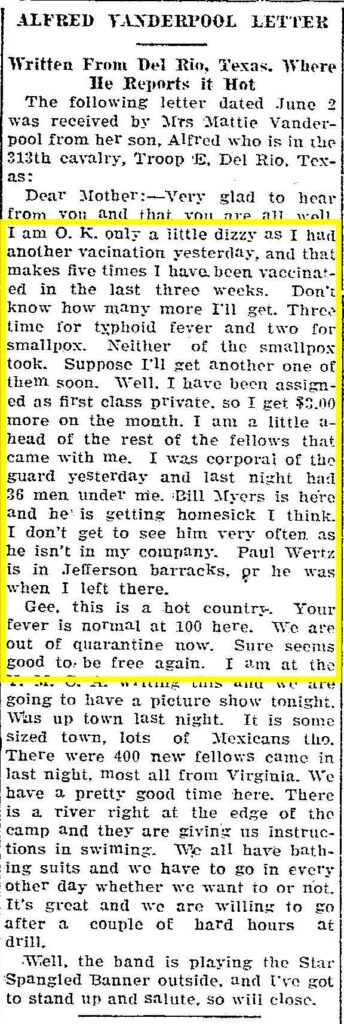

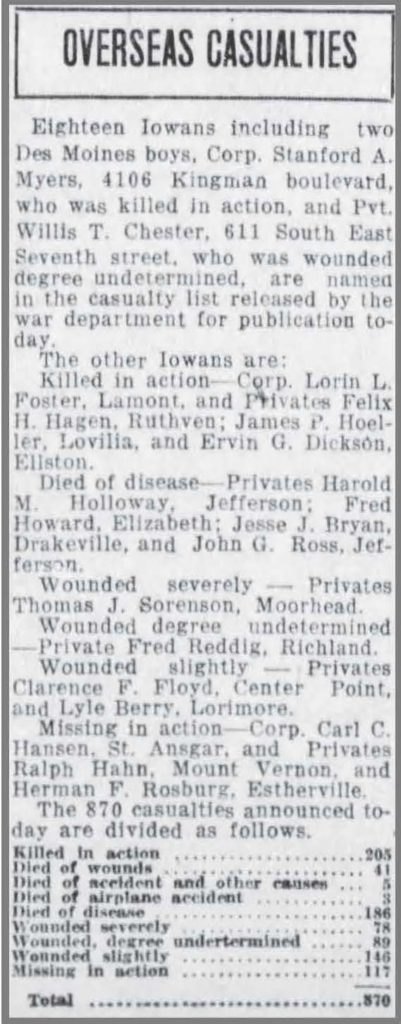

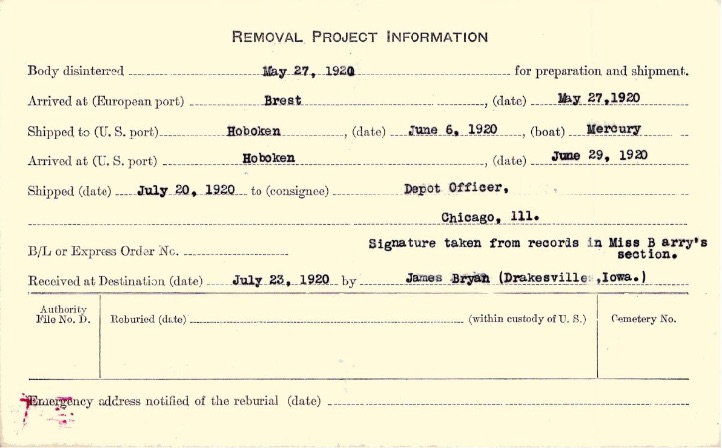

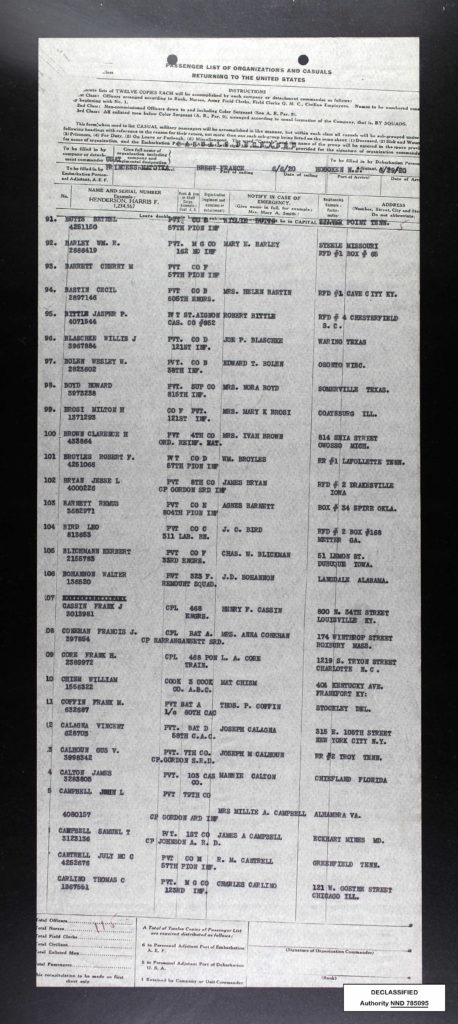

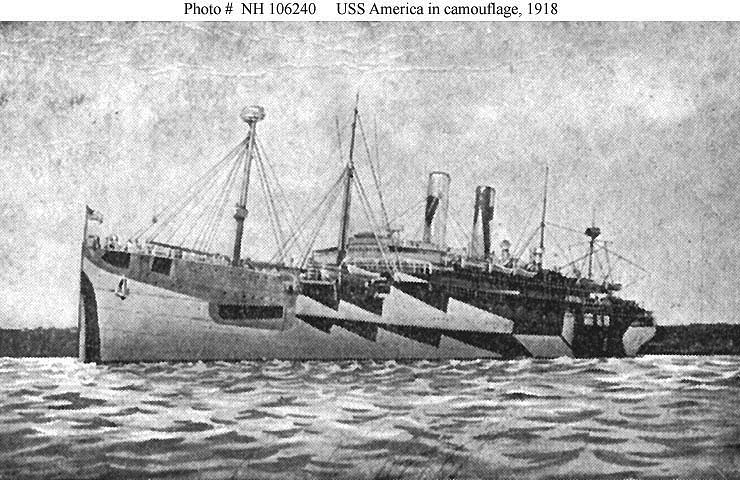

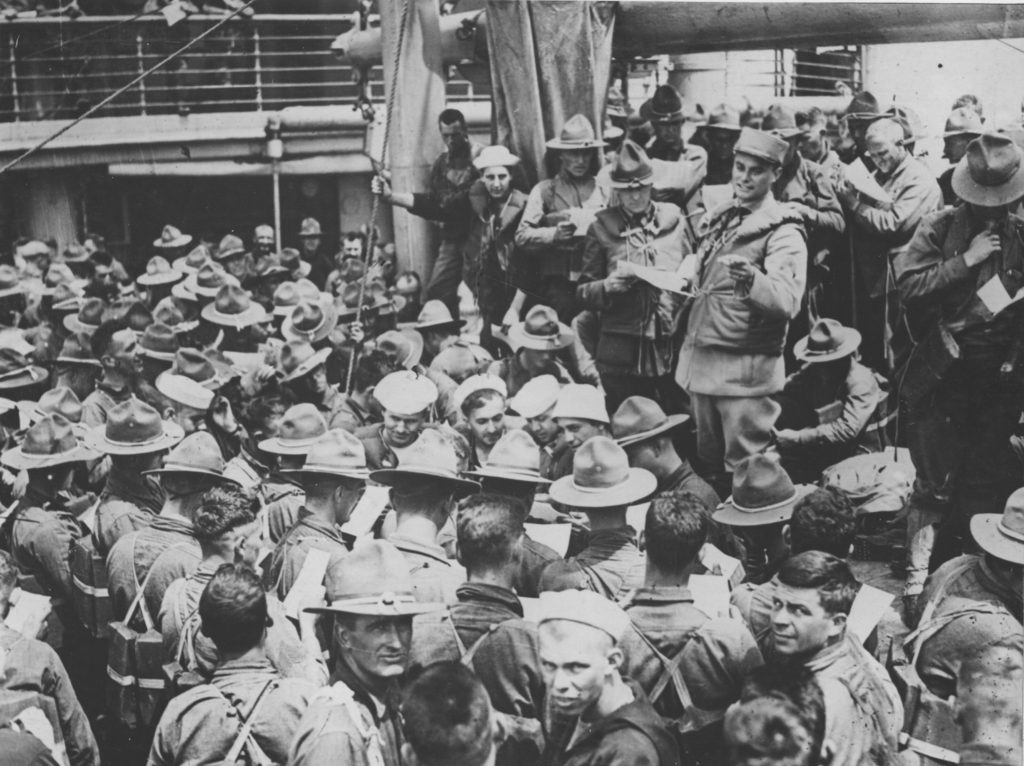

The newspaper carried a few articles about how the soldiers were doing nationally and in the nearby National Guard camp in regards to vaccination and cases of smallpox. What I found more interesting were letters received from some of the local men about their experiences. I have highlighted the parts that reference smallpox, but I found the letters interesting in full. Examined by eighteen doctors?

Poor Alfred Vanderpool ended up in Del Rio, Texas, where he mused that one’s normal fever was 100 degrees. And all those vaccinations! I wonder how they knew his smallpox vaccine did not take?

A young man named Clifford Charles Smith wrote a lengthy letter to the folks back home and it was read to the congregation of the Baptist Church. He described his journey from this southern Iowa county to Camp Dewey Lakes in Michigan. I was going to include his complete letter, but it just doesn’t show up well here, so I’ll just share his description of an unforgettable day.

Be brave and don’t complain about a few vaccinations and boosters! You will pull through it all right and soon feel fine.

Illness is often a time of waiting. Waiting to get well. Waiting to be allowed out of the house. Or into someone’s home. Waiting for school to resume. Maybe even waiting to get your mail.

I wonder how ill Eveline was when she had smallpox, how she spent her convalescence, how much of the talk among her family and friends was about smallpox that year. I wonder if she was good at waiting? Perhaps they wondered, as we do today, “When will this season of illness come to an end?”

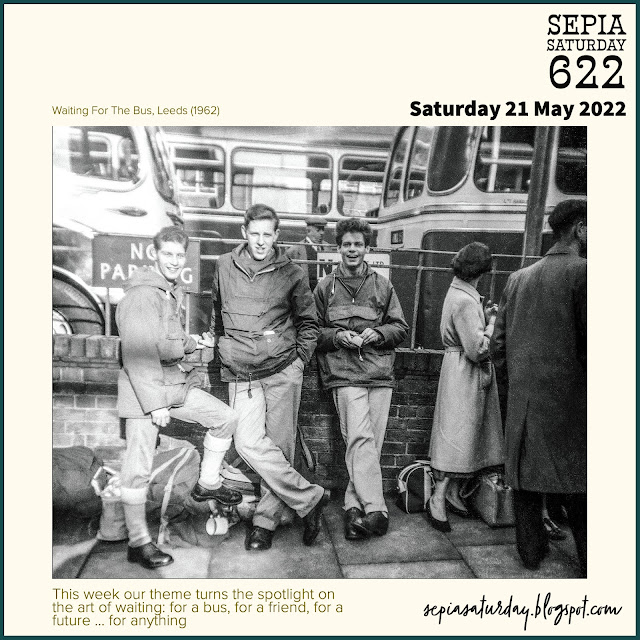

This is my very late contribution to Sepia Saturday, where this week’s participants have responded to the current ephemeral prompt. Don’t wait! Pay them a visit here.