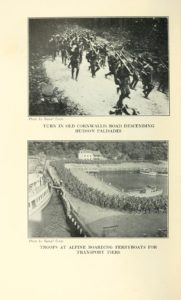

…the silent march out of the camp in the dead of night, down the macadamized highway to the river, the last quarter-mile of it upon a thoroughfare that was half road and half trail, descending stiffly to the water’s edge; there the landing, a platform open to the sky, lighted by incandescent clusters, its bitts mooring a small squadron of river ferry-boats, lumpish craft soon packed to their gates by the brown-clad travelers. Then the dark river, now and then streaked with undulating golden ribbons from waterside lights that grew thicker after an hour or so, when the boat left Spuyten Duyvil Creek behind and began hooting for a passage through the never-ceasing traffic of North River. Then the jutting, brick-and-stone headland of lower Manhattan, thrusting its vague silhouette against the graying eastern sky. Next the pier, tucked in between the projecting sterns of monster transports; the climb up from the ferry-boat; the echoing vault of the roofed pier, dusky in spite of its myriad white arcs; long tables spread with sandwiches and doughnuts, and Red Cross women at rolling coffee urns; inspections, inspections, and more inspections — medical inspections, equipment inspections, alienage inspections, inspections by intelligence officers — and instructions of many sorts.

…the silent march out of the camp in the dead of night, down the macadamized highway to the river, the last quarter-mile of it upon a thoroughfare that was half road and half trail, descending stiffly to the water’s edge; there the landing, a platform open to the sky, lighted by incandescent clusters, its bitts mooring a small squadron of river ferry-boats, lumpish craft soon packed to their gates by the brown-clad travelers. Then the dark river, now and then streaked with undulating golden ribbons from waterside lights that grew thicker after an hour or so, when the boat left Spuyten Duyvil Creek behind and began hooting for a passage through the never-ceasing traffic of North River. Then the jutting, brick-and-stone headland of lower Manhattan, thrusting its vague silhouette against the graying eastern sky. Next the pier, tucked in between the projecting sterns of monster transports; the climb up from the ferry-boat; the echoing vault of the roofed pier, dusky in spite of its myriad white arcs; long tables spread with sandwiches and doughnuts, and Red Cross women at rolling coffee urns; inspections, inspections, and more inspections — medical inspections, equipment inspections, alienage inspections, inspections by intelligence officers — and instructions of many sorts.

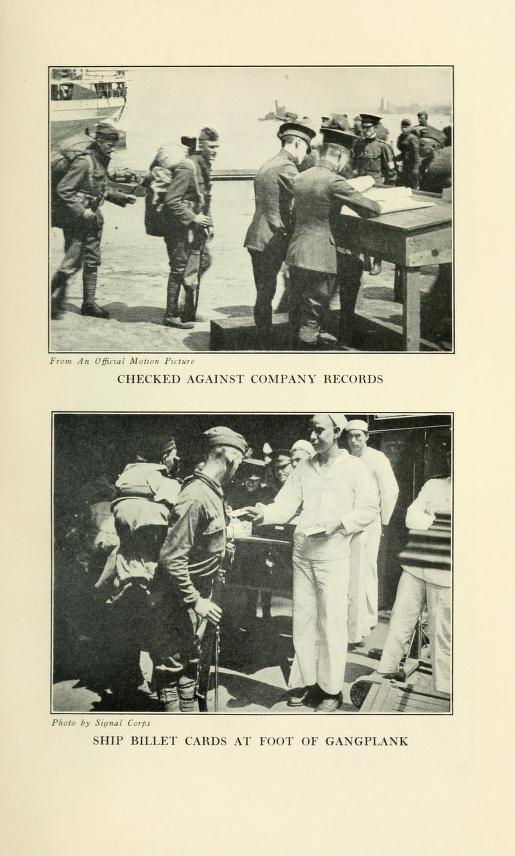

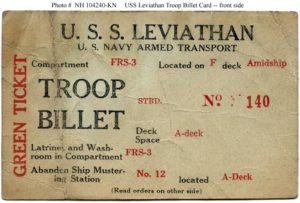

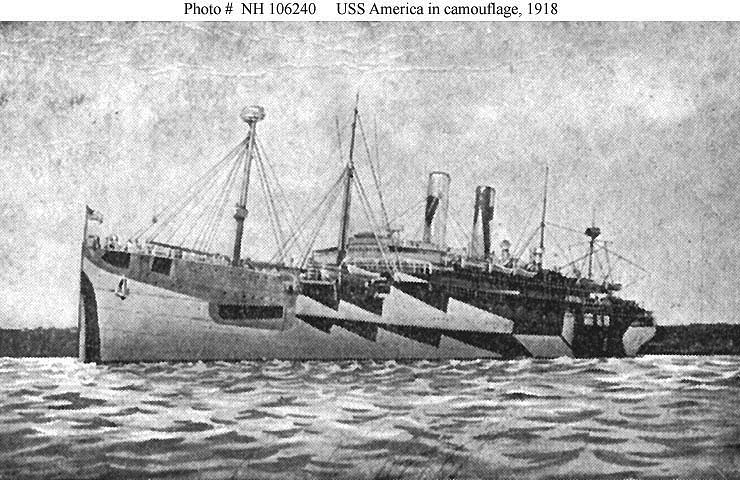

Outside, the city now roars into wakefulness and a new day. The embarkation force comes on duty. Then the gangplank, the loud roll-call, the sharp scrutiny of individuals; at the top of the climb, the mail bag for the “safe-arrival” postcards and the last letters home. After that, the crowded standee berths erected in holds, companion ways, nooks, corners — any place where there had been a trifle of spare room. A peremptory order confined one to these stuffy, congested quarters during the trip down the bay, lest enemy eyes on shore or on some harbor craft mark this as a troopship. And so the chance to sleep, welcome to men drawn and haggard with twenty- four hours on their feet; the awakening to nauseous motion and the vibrant shudder of driving screws; permission to go on deck; the whip of salt wind, refreshing as a cold dip; far to the northward the faint cloud of the Long Island shore, elsewhere tumbling waters; and, from the horizon rim ahead to that of the sunset, a double file of transports, grotesquely streaked with deceptive bands of paint, escorted by flanking destroyers; dirigibles and airplanes overhead and, far in the van, a towed balloon.

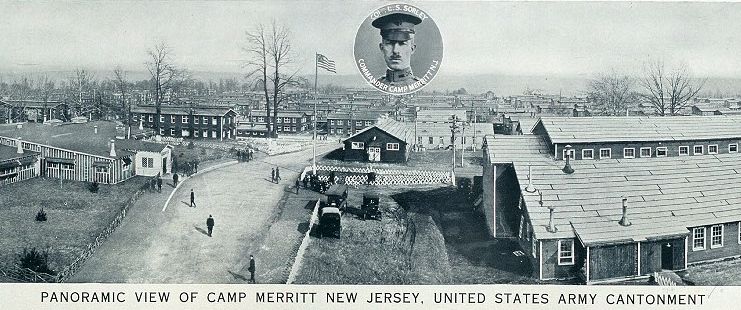

Such is the typical individual soldier’s retrospect of embarkation — an experience brief in point of time, yet so novel to most who underwent it that it impressed its consecutive details deeply in the memory. It began at the embarkation camp, which therefore figured as the bisector between home and overseas service.

The Road to France: the transportation of troops and military supplies, 1917-1918 v. 1, pg. 170-171.

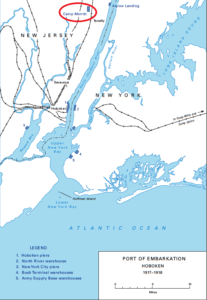

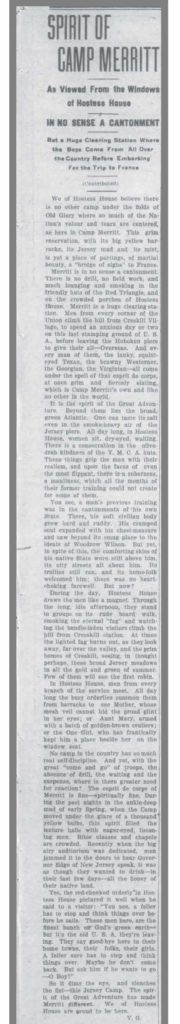

I am continuing a series on how the 1918 influenza epidemic affected my families. The current focus of the series is Jesse James Bryan, first cousin to my grandfather, Thomas Hoskins. I have traced Jesse from his early life in Drakesville, Iowa to the Port of Embarkation at Hoboken, New Jersey. I have only a family Bible, a couple of photographs, and a few records found at ancestry.com so I have to flesh out as much of Jesse’s story as I can from what is available online. The more I look, the more I find, but of course not everything I would like to find.

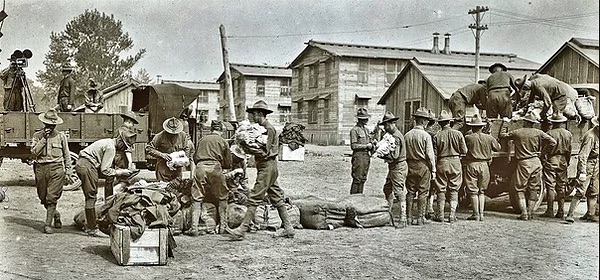

Jesse arrived at the piers early in the morning on September 18th or 19th. He was wearing a new, or almost new, uniform, his overseas cap, and two metal identification tags suspended from his neck. Before leaving Camp Merritt, inspectors had given Jesse a quick once-over to determine if his clothing and equipment were deficient or excessive. It was important that a soldier left for France in a uniform which would give him practically 100% wear because a replacement uniform would have to cross the ocean, taking up valuable space in a cargo hold. Jesse also carried his unwieldy haversack on his back.

Jesse arrived at the piers early in the morning on September 18th or 19th. He was wearing a new, or almost new, uniform, his overseas cap, and two metal identification tags suspended from his neck. Before leaving Camp Merritt, inspectors had given Jesse a quick once-over to determine if his clothing and equipment were deficient or excessive. It was important that a soldier left for France in a uniform which would give him practically 100% wear because a replacement uniform would have to cross the ocean, taking up valuable space in a cargo hold. Jesse also carried his unwieldy haversack on his back.

The Port of Embarkation maintained a disbursing office at New York to pay all embarking officers and men up to the date of their sailings. The payment was made, conveniently, in either francs or pounds, shillings, and pence, so that the soldiers would have no trouble with the money changers on the other side of the Atlantic. So it is likely that Jesse had just received duty pay in francs.

Jesse was tired when he arrived at the piers. The movement of troops from Camp Merritt to the piers took about five hours. All troops to be embarked in a single day were required to be on the piers by eight o’clock in the morning, when the pier inspectors and gangplank workers came on duty. It was vital that the check-in process be accurate, so embarkation occurred in the morning and early afternoon, when the checkers were fresh.

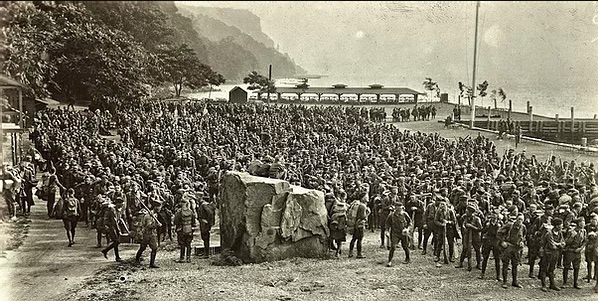

The practice at Camp Merritt was to start the departing troops out in columns of 2,000 or 3,000 men — enough so that each column fully loaded one ferry-boat. The columns left at half-hour intervals, the first ordinarily at one o’clock in the morning. It was from three to four miles from the camp to Alpine Landing, depending on the location of the troops’ quarters in camp, so a column was on the road to the river for at least an hour. If the ferry was loaded in half an hour, it was two-thirty or three o’clock before the first boat started down the Hudson. The ferry took two hours to make the run to lower Manhattan; so the first troops reached the piers shortly before five o’clock, and the last ones arrived by seven-thirty.

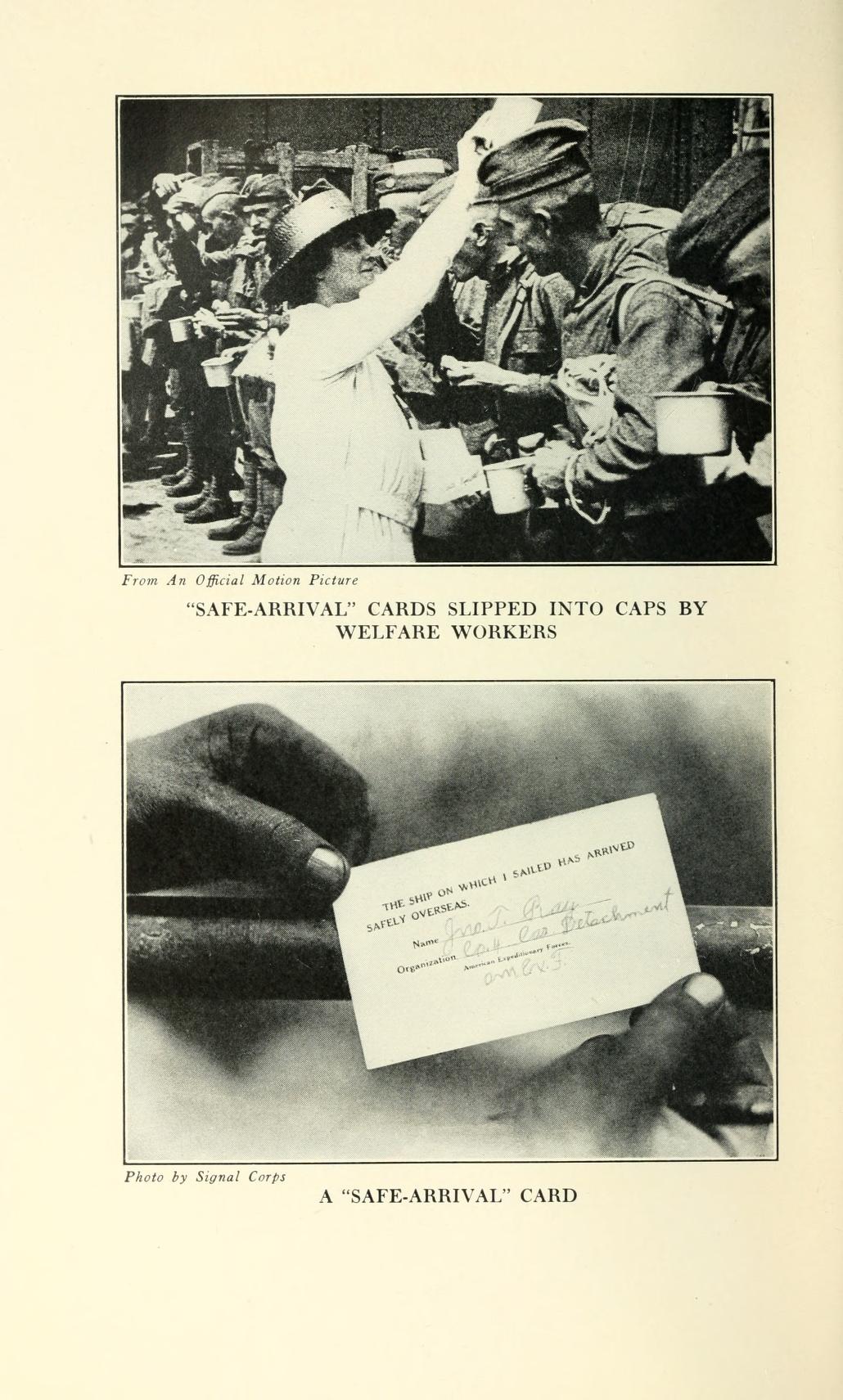

At the pier the men lined up for company roll-call. Then they were allowed to approach the tables set up by canteen workers of the Red Cross, where they could fill up on hot coffee, rolls, ice cream, cookies, or sandwiches, and cigarettes.

After the men had visited the refreshment tables, the Red Cross and Y. M. C. A. workers went among them and distributed “safe-arrival” cards.

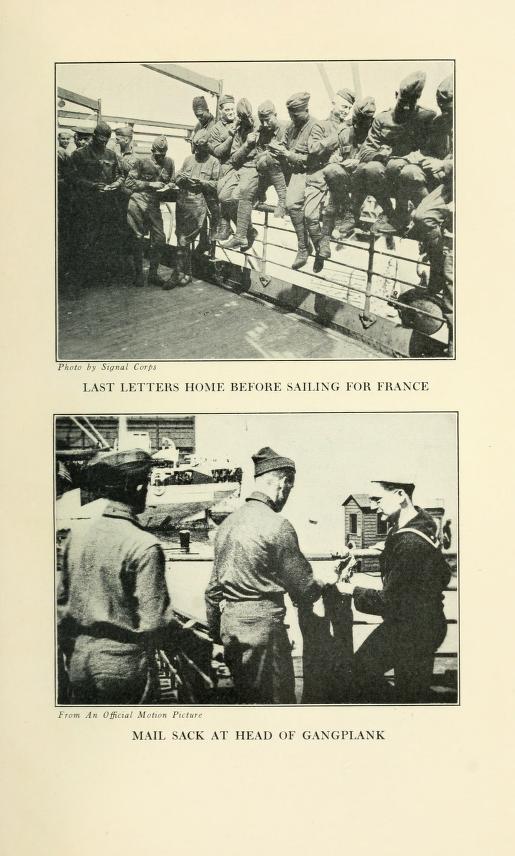

These were printed post cards that read: “The ship on which I sailed has arrived safely overseas.” Jesse signed and addressed as many of these cards as he chose, and held onto them until he passed by a military mail bag at the head of the gangplank. The cards were held in the Hoboken military post office until a cable announced the arrival of the ship in Europe; then the cards were forwarded through regular mail.

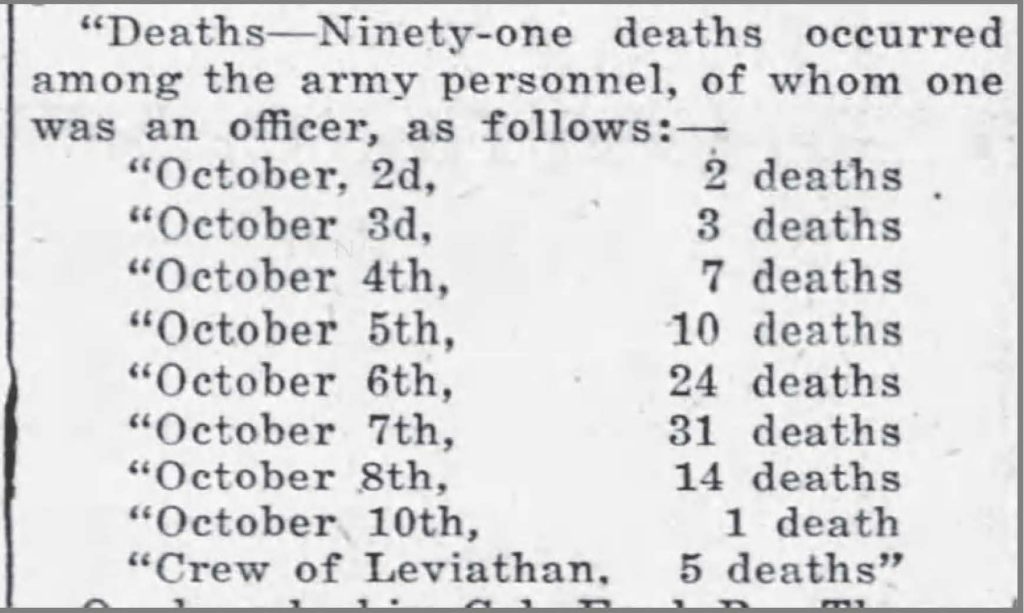

At the piers, Jesse was looked over once again by medical officers making their final inspections. Sometimes, even at this late hour, they pulled out men suspected of disease. During the influenza epidemic, hundreds of men suspected of having the sickness were removed, even after the ships had gone down to the lower bay. Personnel officers also made a final check of the nationality of each passenger.

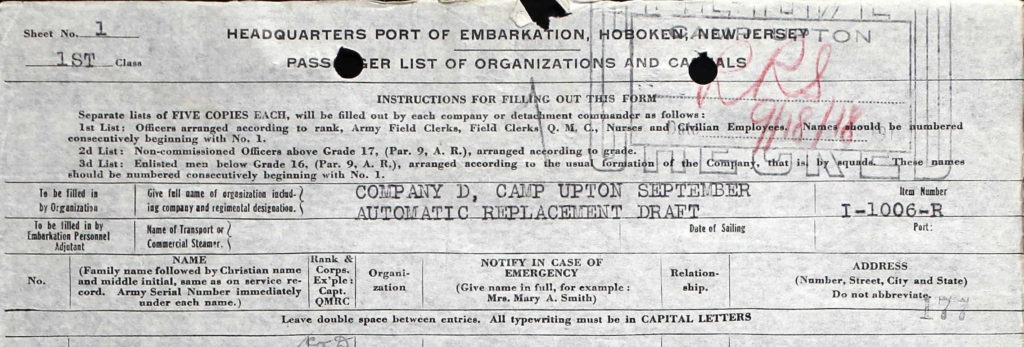

Each company marched to its assigned gangplank. The company commander took his place at the desk with the men’s service records at hand and the soldiers approached the gangplank a squad at a time. When his name was called, Jesse responded by repeating his name – family name first, given name and middle initial afterwards. He had previously received instructions to speak loudly and distinctly.

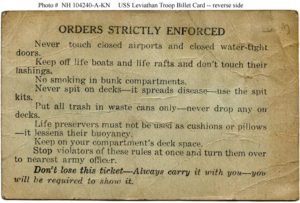

He was then ordered to ascend the gangplank. As Jesse passed the desk, he received a billet card which noted the compartment of the ship in which he was to be quartered and the number of his berth in that compartment. Here is an example of a billet card:

From the top of the gangplank Jesse was escorted to his bunk. To avoid congestion, the men were ordered into their bunks until all had embarked. One would guess that this time was used for some much-needed rest.

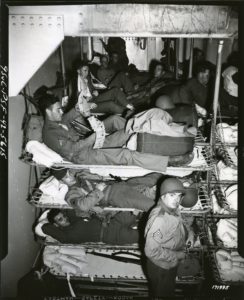

As I noted in my last post, the transport ship that Jesse was assigned to was formerly a German luxury liner. Not any more. As the demand for replacement troops increased, ships were packed to the brim with soldiers. These former luxury liners were retrofitted with standee berths. I haven’t found a photo of the interior of the USS America, but we can assume that Jesse’s berth looked something like these.

The installation of additional cots, standees, and pipe-berths increased the carrying capacity of the entire fleet by twenty-five per cent. A double-shift system (a rotating system in which two soldiers were assigned to a berth so that the berth was always occupied) proved successful on two of the transport ships, and subsequently excess loading was authorized for seven other fast transports — including the America.

Once a compartment was filled, with each man in his bunk, the next step was to stow rifles and haversacks and to learn the prescribed routes to reach wash rooms, mess halls, and abandon ship stations.

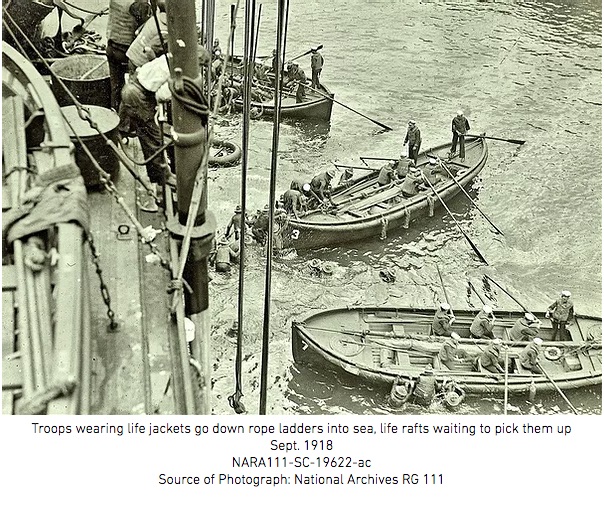

Jesse was given a life preserver when he embarked, and in the danger zone was required to wear it or keep it constantly at hand day and night. Abandon ship drills, also called “drowning drills” by the men, began while the transport ship was still in the harbor. These drills occurred daily at unexpected times throughout the voyage.

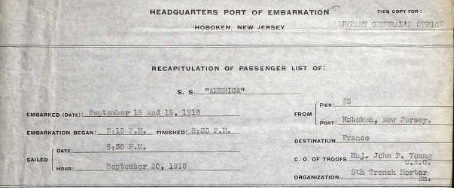

A still healthy Jesse was onboard the America, accustoming himself to cramped quarters with little ventilation, finding his way to the bathroom and mess hall through narrow passageways, practicing a drill that he hoped would not be needed in an ocean he had never seen before, and feeling the motion of the ship at port.

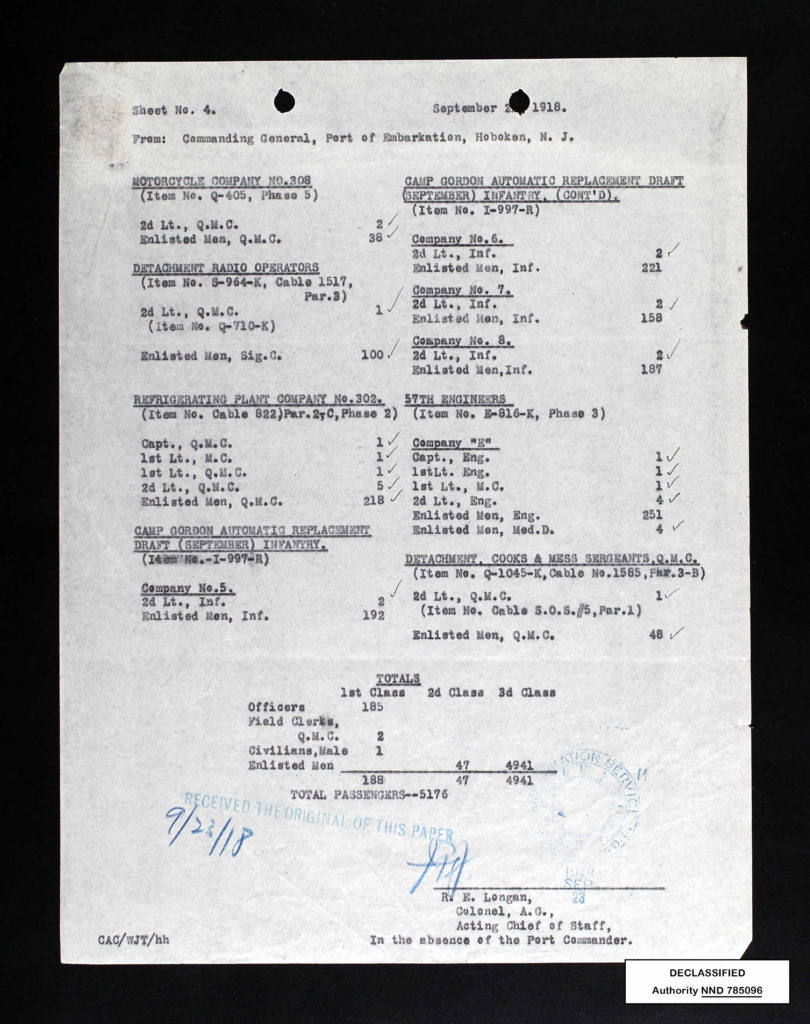

The America sailed at 9:00 p.m. on September 20, 1918 with 1,176 onboard.

The prompt photo this week centers on quilting or quilts – or the letter Q. I will take my cue and Quit for now.

Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

Please visit other participants at Sepia Saturday and see what they have stitched together.

Sources: The Road to France II. The Transportation of Troops and Military Supplies 1917-1918, Vol. 1 and 2 ( New Haven, Yale University Press: 1921)

Gleaves, A. (1921) A History of the Transport Service. [New York, George H. Doran company] [Web.] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/21002087.