I am continuing a series on how the 1918 influenza epidemic affected my families. The current focus of the series is Jesse James Bryan, first cousin to my grandfather, Thomas Hoskins. I have traced Jesse from his early life in Drakesville, Iowa to the transport ship America during WW1. I have only a family Bible, a couple of photographs, and a few records found at ancestry.com so I have to flesh out as much of Jesse’s story as I can from what is available online. The more I look, the more I find, but of course not everything I would like to find.

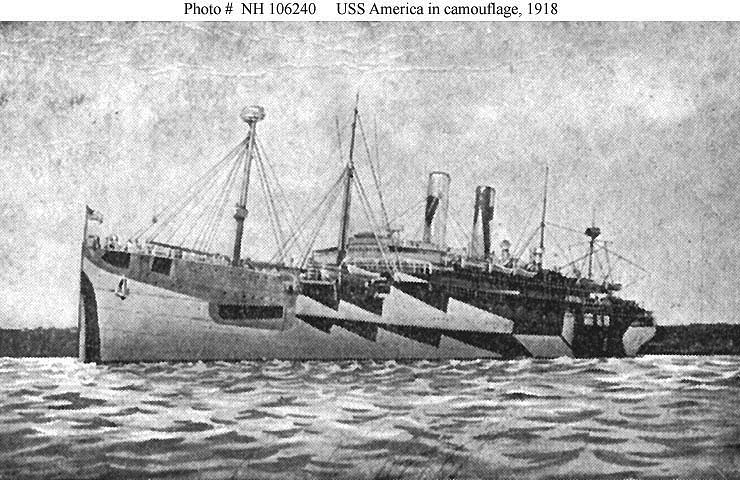

The USS America sailed at 9:00 p.m. on Friday, September 20, 1918, with Jesse Bryan onboard.

The transport ships America and Agamemnon left port together, escorted by the destroyer USS Bell headed for Brest, France.

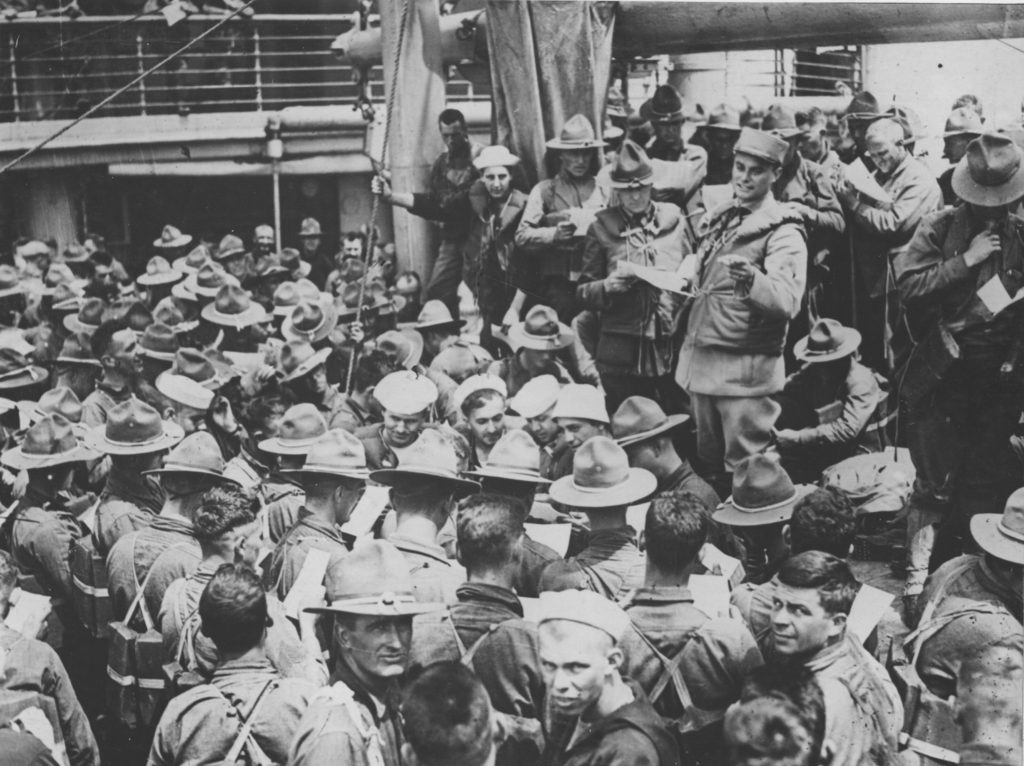

With cramped conditions, seasickness, enforced darkness at night, zigzagging maneuvers and no sleep while in the danger zone, unscheduled daily abandon ship drills – some at night, and whatever duties he was assigned, Jesse must have counted down the days until this trip would end. Of course there is no way to know Jesse’s mindset – anticipation, dread, or both.

Flashlight taken below water line on a crowded U.S.A. Transport showing how the men live. File Unit: American Library Association – Dispatch, 1917 – 1918

Series: American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, 1917 – 1918

Record Group 165: Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, 1860 – 1952

There were diversions on the transport ships to keep up morale. Maybe Jesse watched a boxing match,

Troops on board a transport being entertained by a boxing match between two soldiers. Series: Photographs of American Military Activities, ca. 1918 – ca. 1981

Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 – 1985

participated in a song service,

Song service aboard US transport

National Archives Catalog Record Group 165: Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, 1860 – 1952

or took French lessons,

A study in French. These lessons are given by a French Officer enroute to France aboard a U.S.A. Transport. In the Submarine Zone and everyone has a life preserver

National Archives Identifier:17343016Local Identifier:165-WW-27A-9Creator(s):War Department. 1789-9/18/1947

I feel lucky to have found the following information on the Naval History and Heritage Command website that pertains specifically to Jesse’s voyage.

“America parted from George Washington and Von Steuben on 2 September 1918 and reached the Boston Navy Yard on the 7th. Following dry docking, voyage repairs, and the embarkation of another contingent of troops, she arrived at Hoboken on the morning of the 17th. Three days later, she cleared the port, in company with Agamemnon, bound for France on her ninth transatlantic voyage cycle.

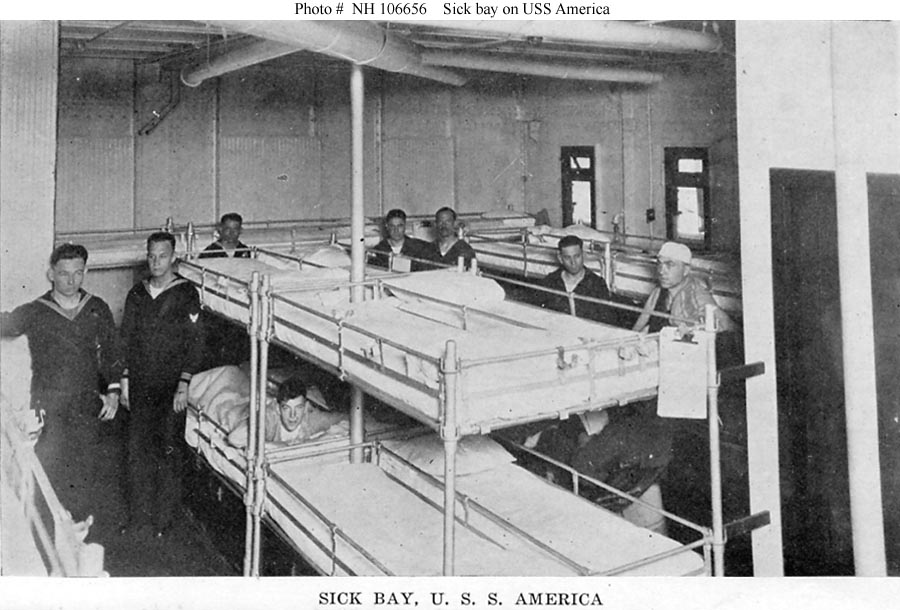

By this time, an influenza epidemic was raging in the United States and Europe and had taken countless lives. From its first appearance, special precautions had been taken on board America to protect both her ship’s company and passengers from this scourge. The sanitary measures had succeeded in keeping all in the ship healthy. However, this group of soldiers, who had come on board at Boston where the epidemic had been raging, brought the “flu.” As a result, 997 cases of “flu” and pneumonia occurred among the embarked soldiers during the passage to France, while 56 cases broke out among the 940 men in the crew. Before the transport completed the round-trip voyage and arrived back at Hoboken, 53 soldiers and 2 sailors had died on board. This comparatively low death rate (some ships lost considerably more men) can be attributed to the almost super-human efforts of the ship’s doctors and corpsmen, as well as the embarked units’ medical personnel. Forty-two of the 53 deaths among the troops occurred during the time the ship lay at anchor at Brest from 29 September to 2 October.”

Until I read this, I was unaware that troops had boarded the America before it made port in Hoboken. This account singles out Boston as the source of influenza infection onboard ship, but troops arrived from other embarkation camps where influenza had also taken hold.

The America would have been fitted with a surgeons’ examining room, dispensary, a laboratory, dental office, dressing room, operating room, special treatment room, sick bay and isolation ward as well as several dispensaries and dressing stations throughout the ship for minor cases.

The quote above does not specify how many of the 55 deaths on the America occurred during each leg of the ship’s round trip, only that 42 died while it was at anchor in Brest. Of the 13 deaths that occurred while at sea, I am left to wonder how many died before arriving at Brest. If there were deaths before docking in Brest, Jesse may have participated in a burial at sea.

The History of Transport Service recounts a memory of a burial at sea on the USS Seattle.

“The armored Cruiser Seattle was six days out on her third war cruise as ocean escort for troop convoy. News travels quickly in a ship, and before the morning muster at quarters we all had heard that one of the crew, ill of pneumonia, had passed away during the night.

The people of a ship are thrown intimately together on an ocean voyage and, in this case, war service added to the community spirit. The loss of our shipmate touched us all. Little was said but much thought was given as we assembled aft in answer to the tolling of the bell and the boatswain’s pipe of the solemn call, “All hands bury the dead.”

The service was conducted on the starboard side of the quarterdeck, the official place for ceremonies in a man-of-war. The bier was mounted outboard and draped with flags. Just inboard and forward stood the escort under arms. Space was left for the funeral party to march aft from inside the superstructure.

At the appointed hour, the ship’s company, numbering about one thousand, ranged themselves in inverse order of rank around and abaft the turret guns. At the rail was rigged the gangway over which the body was to make its final passage from ship to sea.

The flag was then lowered to half-mast and the accompanying troopships in the convoy also lowered their ensigns to half-mast, thus joining in the ceremony, rendering homage in memorial of the life given just as truly in service for the cause as though it had been lost by the blow of a torpedo or an enemy bullet.

When all was ready the band played the funeral dirge, while the body bearers with the casket, followed by the pall bearers and Chaplain, marched aft at “slow time.” The escort came to “present arms” and all hands stood at “attention” until the casket was placed on the bier and the dirge finished.

The Chaplain read the church services. At their completion the band played “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Then all hands “uncovered,” the escort again came to “present arms,” the Boatswain and his mates piped the side, and in reverent quiet–even the ship’s engines were stopped–the body enfolded in the Stars and Stripes was committed to the deep.

Three volleys of musketry were fired, and the bugler ended the ceremony by sounding taps. The familiar and now mournful notes echoed in all hearts the call to the final sleep.

After a short pause the Captain gave the word “Carry on.” The band struck up a march and the divisions went forward at “quick time” to their respective parts of the ship. Gun drills were resumed. Carpenters, ship fitters, blacksmiths, and machinists picked up their tools. The propellers again churned the water, flags were masted, and the ship’s work continued.”

As reported above, the America sat at anchor from September 29-October 2 in Brest. During that brief time, forty-two men died. How awful that must have been!

The story passed down in Jesse’s family is that Jesse contracted the virus while on the ship. He did not die until about six weeks after disembarking. Without military service records, it is impossible to know just what happened next for Jesse. Was Jesse counted among the 997 cases of flu and pneumonia of embarked soldiers on the America and go directly to a hospital? Or did his symptoms manifest in camp a few days later?

Some victims of the influenza virus died quickly – within a day or two. The majority died within 3-10 days or two weeks. Jesse died November 13, 1918, well outside the usual timeframe if he was infected while still on the ship.

Descriptions of the virulent influenza are hard to read. As the illness progressed beyond the fever, headaches and body aches of a regular flu, the lungs filled with bodily fluids, causing discoloration of the hands, feet and face. Bloody fluids seeped from the nose and ears. As fluids built up in the lungs, it caused suffocation. Some experienced delirium and or lost consciousness. Some victims appeared to be improving and then developed bacterial pneumonia. Interestingly, I read that the new drug, aspirin, developed by the German company Bayer, was probably over-prescribed, and that it is now believed that many of the October deaths were caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning.

I don’t know where Jesse may have been hospitalized. There were several camp and base hospitals near Brest. Most were opening or adding space around the time of Jesse’s arrival in France to serve wounded and sick soldiers prior to their return to the United States. From what I read about a few of the camp hospitals, most seemed to have serious sewage/sanitation problems.

Unloading patients from ambulances, Camp Hospital 33. Brest, Finistere, France. 12-31-1918 “Series: Photographs of American Military Activities, ca. 1918 – ca. 1981

Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 – 1985

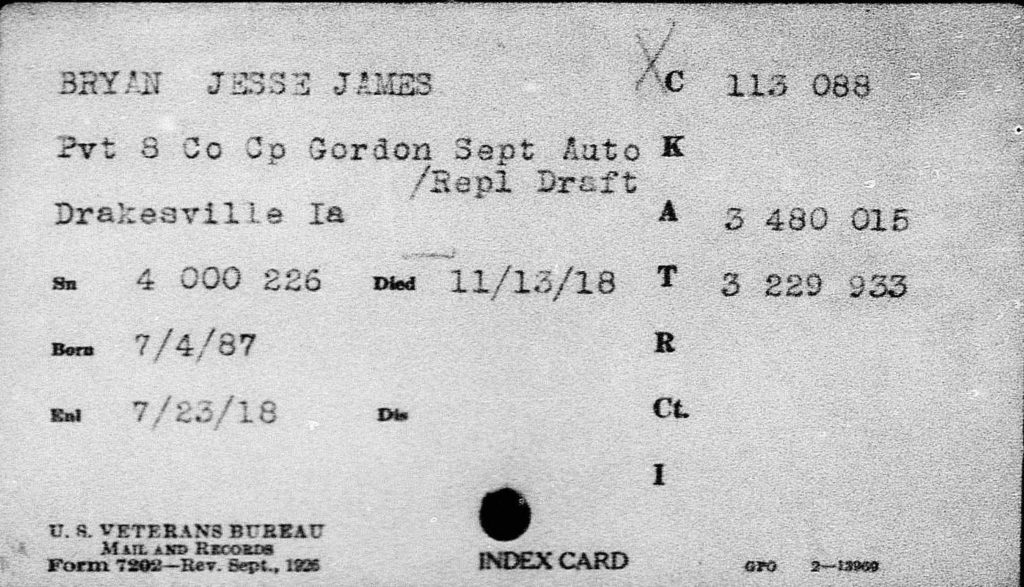

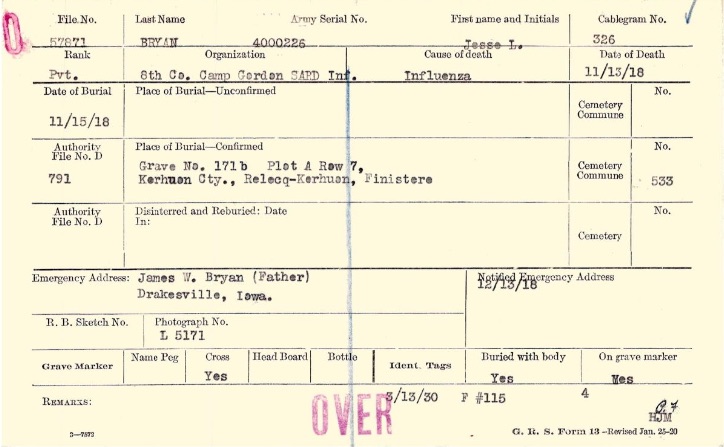

The military grave registration card for Jesse details his burial in Kerhuon Cemetery. Google Maps says Le Relecq-Kerhuon is about a fifteen minute drive from Brest.

I’m not sure if I found the cemetery where Jesse was buried, but maybe this is it.

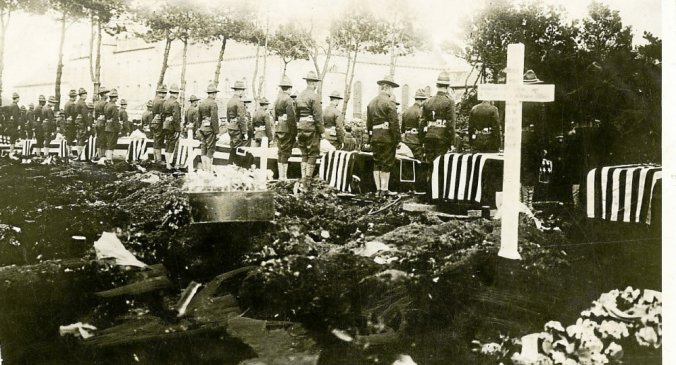

The burial ceremony for Jesse may have looked something like the one pictured below at a cemetery in Brest.

At the Kerfautras cemetery, a ceremony for members of the American army, during the Spanish flu epidemic, hence the large number of coffins. (Archives of Brest Métropole)

I have not been able to answer all of my questions about Jesse’s life and death, but I am satisfied with what I have found. Maybe those military records will surface one day.

Jesse’s story is not quite finished, so I’ll be back with the rest of his story.

P.S. I intended to have this post finished to share last week, but present day life intruded on history. Cancer can’t seem to leave me alone, so I’ve had to spend some time with doctors and scans. I’ve just gotten back to regular blogging in recent months and so I really hope I can keep that going!

Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

b;

This has been a terrific series, Kathy. Your research and extra documentation has added a full dimension to Jesse’s life and brief wartime experience. I was appalled to read about the aspirin poisoning on that link. Last year it would have seemed a sad mistake of early medical science, but in 2020 it sounds like a echo of our own tragic pandemic.

Have you considered contacting the cemetery? They might provide a photo of Jesse’s marker. In my research I’ve found online numerous regimental histories written by army officers as a memento of their unit’s service. They often have details on the troop movements as well as rosters of the soldiers. A search for the regiment number and commanding officer might find such an album.

And I wish you well, Kathy, and hope you return to good health soon.

I haven’t found a regiment for Jesse – I think because the replacement troops were not assigned until they reached France. But I could be mistaken. His story is not quite complete, so stay tuned.

And thank you for the good wishes!

Fascinating research about Jesse. I knew that the influenza outbreak was horrific, but your research really brings it to life. Thank you for sharing all your wonderful family history.

Thank you for reading and leaving a comment. I am learning a lot.

This has been an incredible series, Kathy, about Jesse and the military side of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which mirrors my series about my dad’s Uncle Albert Barney Charboneau’s civilian death in October, the month before Jesse’s passing.

I agree with Mike about other possible sources for details about Jesse. How sad that he was buried so far from home, but the cemetery may indeed have more details.

My best wishes to you this holiday season and for the New Year, and for your return to good health. It has been a pleasure to write alongside you these last few months and share our respective families’ stories about the 1918 influenza pandemic.

It has been fun and interesting to read and write along side you, Molly. There is one more piece to Jesse’s story that I have to share. Stay tuned!

This was a great article! You might want to check out this map showing the spread of the 1866 cholera epidemic in the US Army. The visuals are great. I am trying to trace my grandfather’s WWI experience and your blog has been a great help

Will try the link again

https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/a0ec7d32c37a2422a5e672bdcd7ecc11/the-u-s-army-cholera-epidemic-of-1866/index.html

Thank you for the interesting link! I’m not aware of a cholera tie to my families, but I’ll be on the lookout!

It must have been so disheartening to have been so careful on the “America” with regard to the epidemic and then to have the flu brought onboard at one single location and infect so many that had been safe till then. The mention of aspirin poisoning was interesting. I’d not heard of that before.