Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

Next in a series on how epidemics, pandemics, and other public health crises have affected my families.

You can catch up on the series here:

Woodye Webber

Lydia Elizabeth Strange

Jesse J. Bryan, part 1

Ice Cream for what ails you

Jesse J. Bryan at Camp Gordon

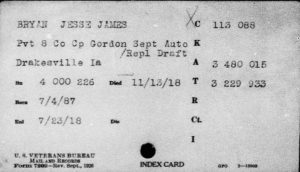

I’m continuing to piece together, as best I can, the life of Jesse (Joe) Bryan who was a first cousin to my grandfather Thomas Hoskins. As noted previously, Jesse registered for the draft on 5 June 1917 and enlisted on 23 July 1918. His military training was at Camp Gordon, GA, where he was called to the September Automatic Replacement Draft.

I assumed that training at Camp Gordon would last at least six weeks, but this excerpt from Learning the Lessons of Lethality: The Army’s Cycle of Basic Combat Training, 1918-2019 states that his training at Camp Gordon may have only been twelve days.

“The Army began its initial foray into individual replacement training following the overseas deployment of its combat divisions in late spring 1918. Heavy combat losses required an individual replacement system to maintain the integrity of front line units. Depot staffs provided immunizations, medical examinations, job classification interviews, proficiency testing, and initial uniform issue to new recruits. The overworked and understaffed cadre had little time to conduct Soldier training other than rudimentary manual of arms drill and marching. The Army established fourteen Replacement Training Centers (RTCs) at camps vacated by deployed divisions in spring 1918. The hastily formed centers and training cadre required time to incorporate the systems and processes required for individual Soldier training. The centers were operating at full capacity by August 1918. The cadre created a 12-day training program for individual Soldier training and received augmentation from veteran officers and non-commissioned officers returning from France. New troops were assigned to a replacement battalion for additional training upon arrival in France. Replacement battalions emulated the French and British models and conducted training designed to reinforce basic Soldier skills and accustom green men to the operating environment.”

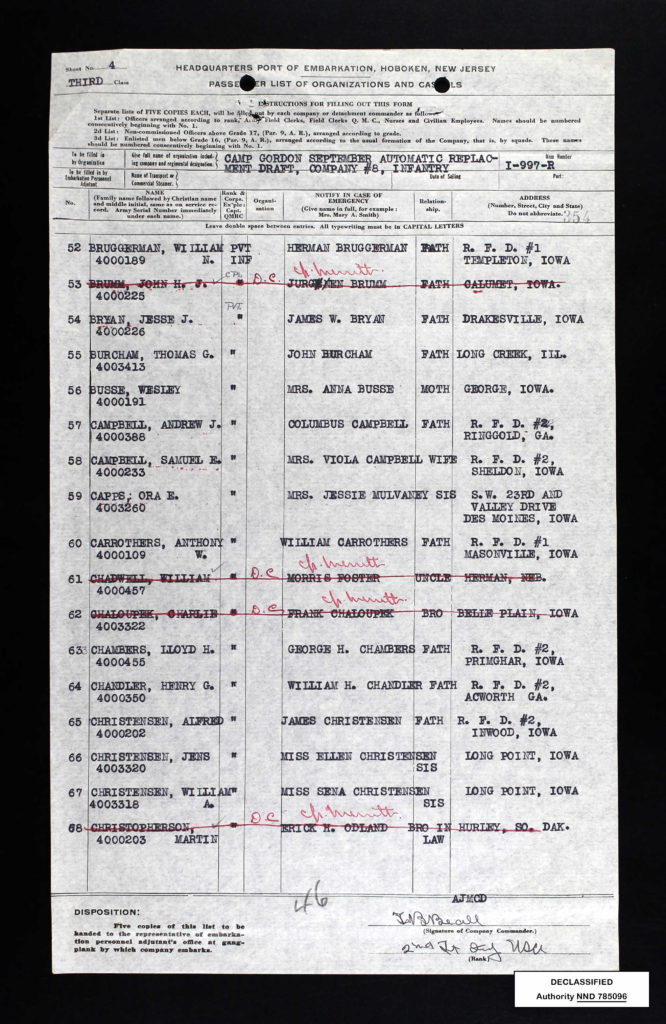

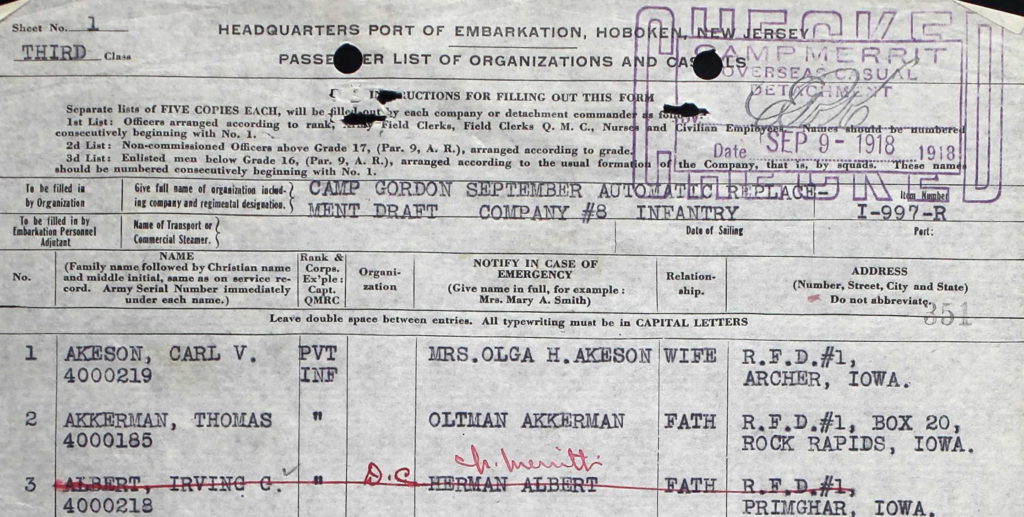

The next clue is the document below. Jesse is third on this passenger list, #54.

This page doesn’t offer much information – no ship named, no date of sailing, no date, no mention of the embarkation camp. I had made a note of a departure date of September 9th. Where did I get it? I went back to ancestry.com, where I obtained the record. The soldiers in his company are listed in alphabetical order, so I backed up to the beginning of the list for Company 8 and saw that a stamp at the top of the page gave the September 9 date.

Camp Merrit

Overseas Casual

Detachment

Sep 9 1918

And it looks like the word outside the box is “checked.”

It never fails to astound me how much information can be right in front of my face and I simply don’t see it. All I had seen was the date. Mystery solved. When Jesse left Camp Gordon, he want to Camp Merrit, NJ. He was checked in on September 9th.

I have requested Jesse’s military records, but with shutdowns due to our current pandemic, only emergency requests are being handled at this time. I don’t expect to receive anything anyway. Older records kept at the National Archives in St. Louis were destroyed by a fire sometime in the 1970s. I tried to get military records for Jesse’s brother a few years ago to no avail. So … I’m left to guess.

Here is what I think I know:

* Jesse was checked in at Camp Merritt, on September 9, 1918. If he was in a 12-day training program at Camp Gordon, it seems like he would have been transferred to Camp Merritt or another embarkation camp by mid-August.

* Jesse’s youngest sister told her daughter that she saw Jesse when he came home on furlough before being shipped out. A twelve-day training would have accommodated a furlough from Camp Gordon before going to New Jersey, but I wonder if he just went home before his enlistment in Georgia in July. Knowing if he was in uniform when he went home would answer that question.

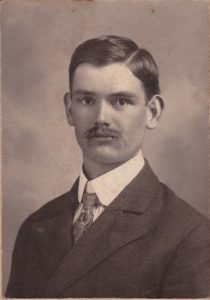

* Jesse had a professional photograph made during his time at Camp Merritt.

Jesse’s cap looked unfamiliar to me, with that dip in the middle creating almost flaps on either side, so I went looking for information.

The cap he is wearing is an overseas cap and was not given to soldiers until they were at an embarkation camp. Maybe Jesse is expressing his personal style in the way he is wearing his cap, or maybe this version is meant to be worn this way.

“The various modes in which the overseas caps were worn after they had been issued to the men of the 36th Infantry Division at Camp Mills in August of 1918, was mentioned in a history of that organization:

Rivaling the Sam Browne belt in its importance was the new overseas cap which was to take the place of the campaign hat. Officers and men shared in the task of adjusting this new contrivance to their persons. A remarkable variety of ideas were developed as to just how the cap should be placed on the head, many attempting to wear it after the fashion of a “stocking cap” while others gave an excellent impression of Napoleon. These new articles of apparel however, were not allowed to be worn in New York, where the men and officers went as often as time and money allowed. The privilege of seeing New York was not given to all however. Some of the units arriving at the camp August 14, were equipped and sent aboard the transports at Hoboken the same day, not being allowed to spend a night in the camp, so great was the necessity for loading the ships preparatory to departure … Not all the troops were equipped with the new overseas cap, some of them being compelled to await their arrival at the training area in France before they received this part of their equipment.

The Story of the 36th, Captain Benjamin H. Chastaine, 1920, page 31″

This suggests that Jesse had to keep his hat in his pocket while in NYC when he was out and about in the city. If you are interested in more photos and information about overseas caps, check here.

The back of Jesse’s photo gives the name of the photography studio: Walter Studio, 28 East 14th Street, New York City. I found a recent photo of the building at 28 East 14th St. on a blog urging landmark status. The article names previous occupants, but not the photography studio.

The back of Jesse’s photo gives the name of the photography studio: Walter Studio, 28 East 14th Street, New York City. I found a recent photo of the building at 28 East 14th St. on a blog urging landmark status. The article names previous occupants, but not the photography studio.

I obtained the photograph of Jesse from the Iowa State Historical Society. The Iowa State Department of History and Archives actively requested photographs of World War I casualties from families of the deceased during, and for a few years after, the war.

So – Jesse had to be at Camp Merritt long enough for at least a day trip to the city.

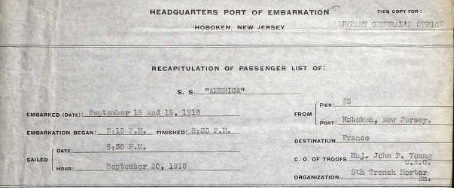

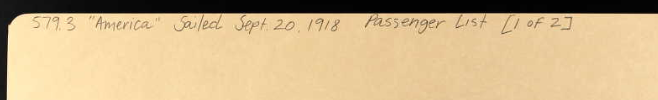

Backing up even further in the lengthy passenger list, I finally found another piece to the puzzle. The file folder that held the passenger list where Jesse is listed.

A few pages in, and I have the dates that the soldiers were loaded onto the ship.

That puts Jesse at Camp Merritt about ten days: Monday, September 9-Wednesday, September 18. Now that I have a possible timeline, I’ll take a closer look at Camp Merritt next time.

… and to tie in to Sepia Saturday, I’ll speculate that Jesse got a glimpse of a lighthouse while in NYC.

See what other Sepians are shining a light on today: Sepia Saturday