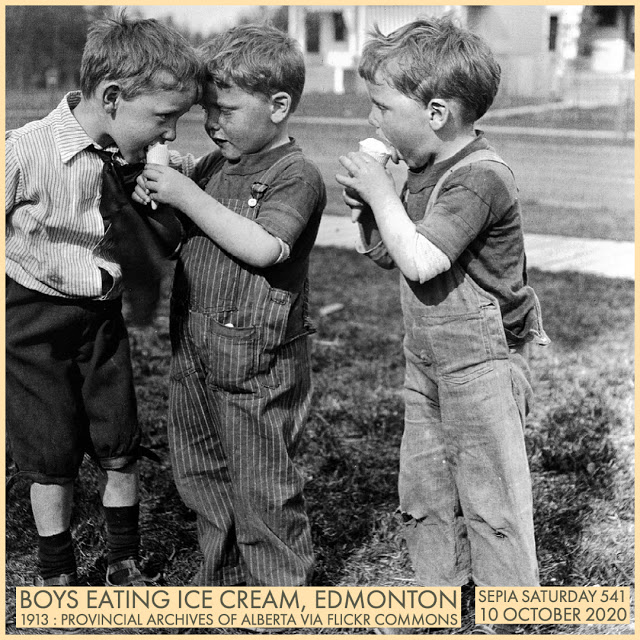

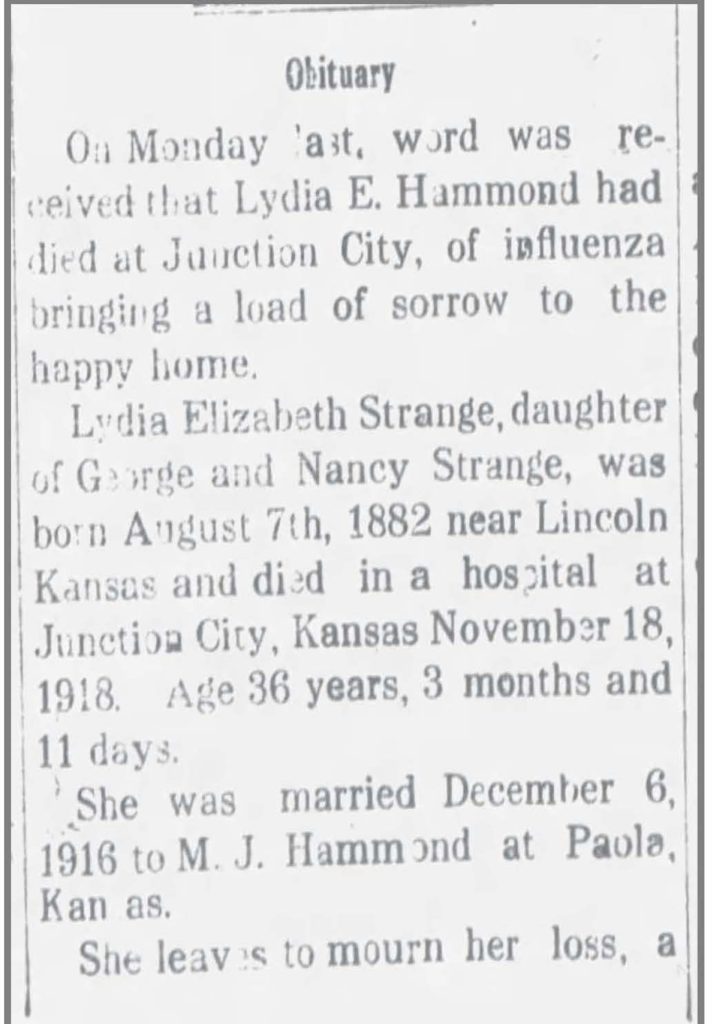

Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

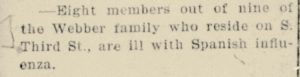

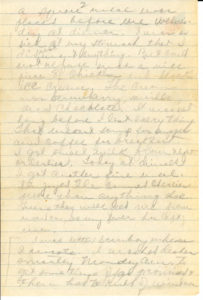

I have spent a lot of time this week working on a project I started several (ahem) years ago. I have a photo album my Grandmother Abbie made and I’ve been reconstructing it, scanning all the photos, and sharing it as a facebook album with family members. One of the photos in Abbie’s photo album is this shot of her husband, Charles Smith, buying ice cream.

It was taken in 1953, but I don’t have a location. Somewhere in Iowa, I would guess. My grandfather was not a thin man and we might suppose he ate his share of ice cream over the years. He and my grandmother ran a gas station, cafe, grocery – a full service truck stop, in southeastern Iowa. I’ve written about them and their home/business a couple of times. This post provides the most background: Charles’ and Abbie’s Place.

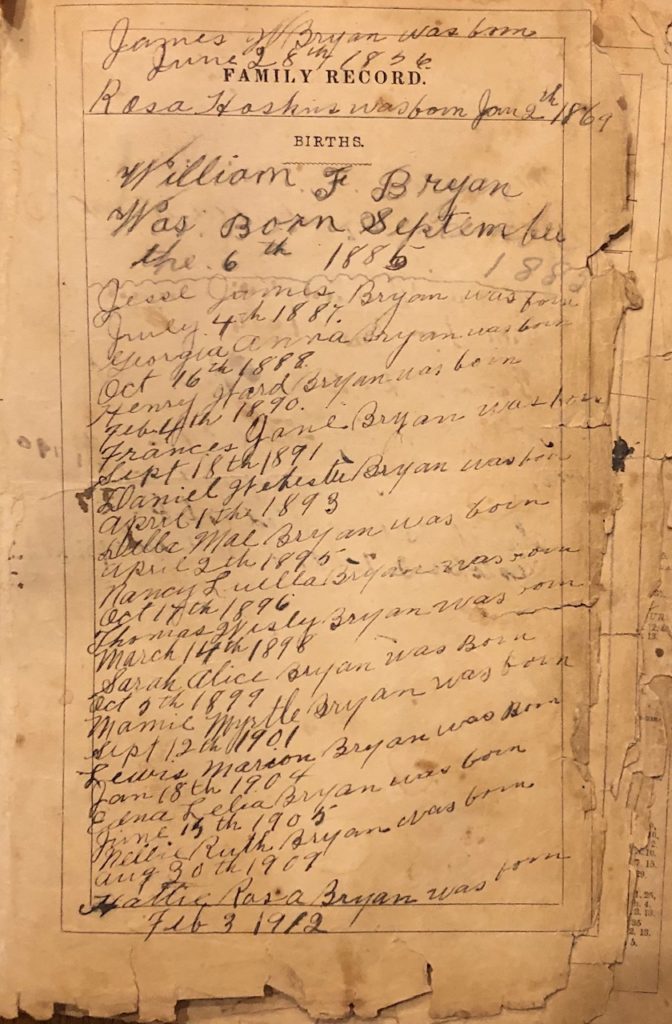

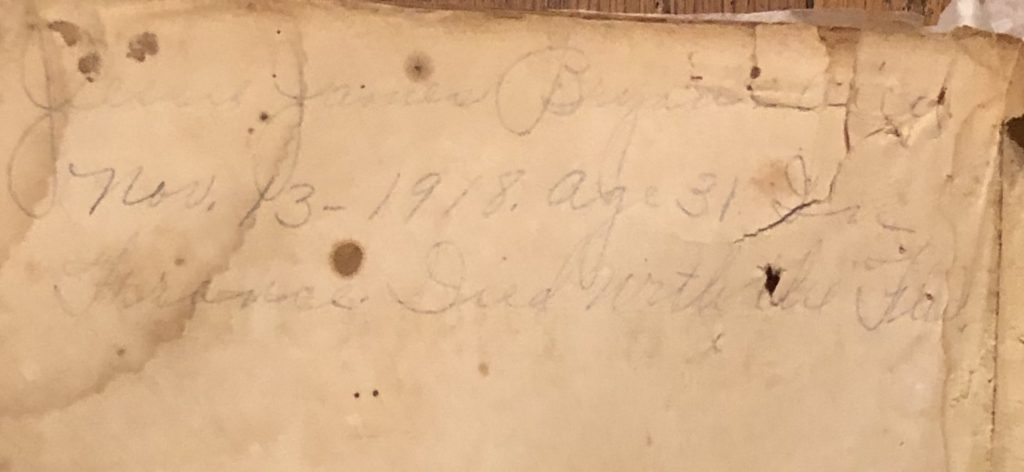

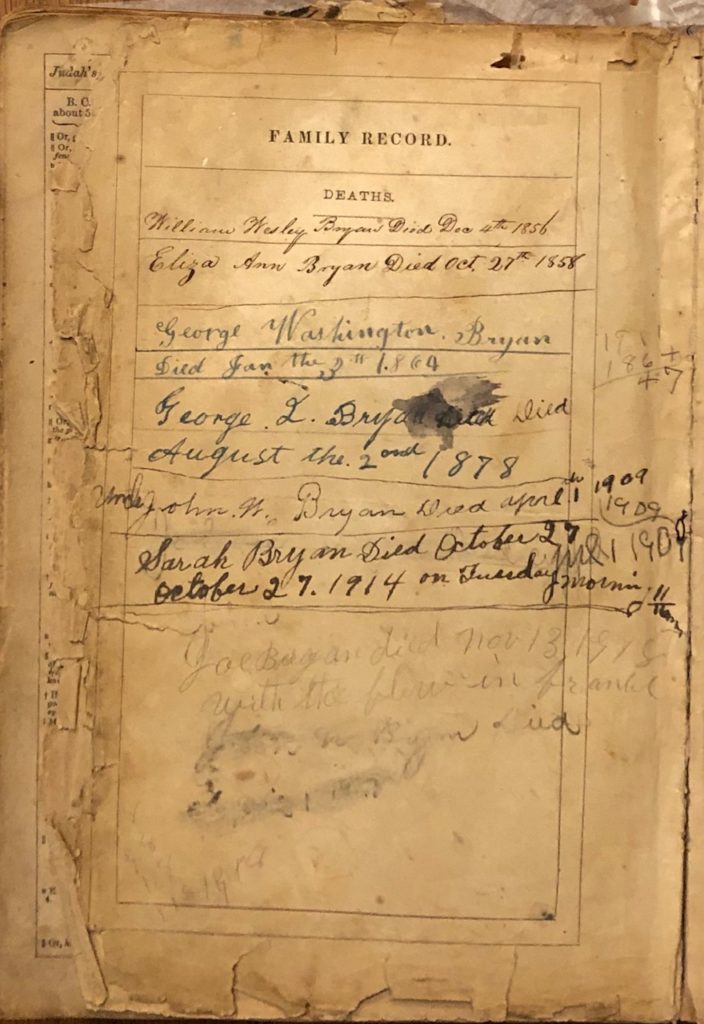

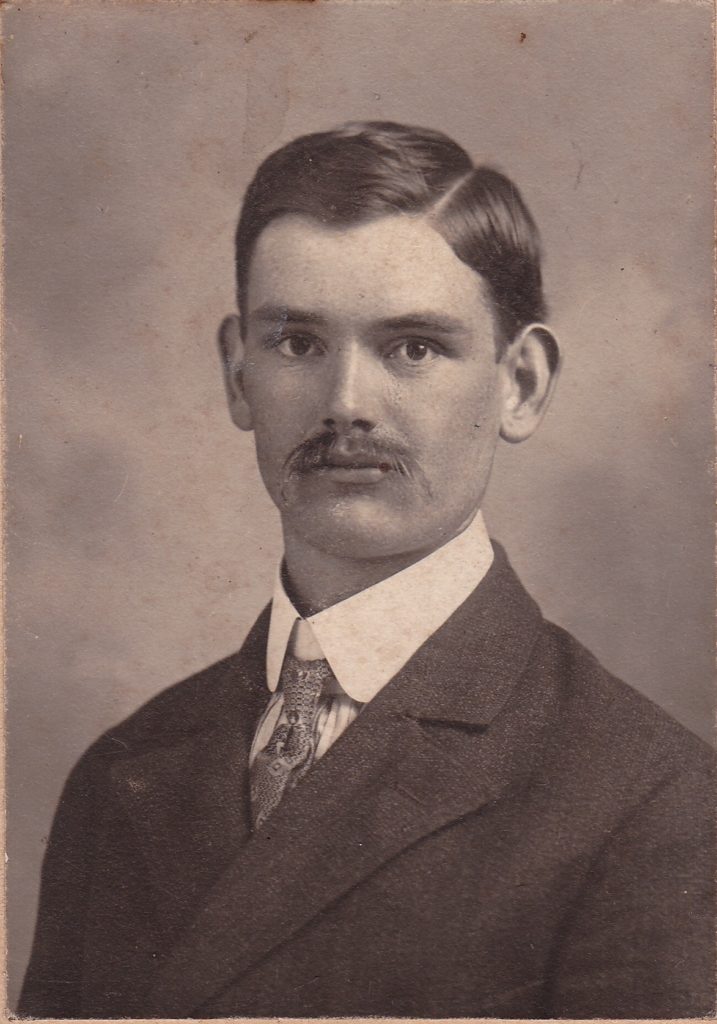

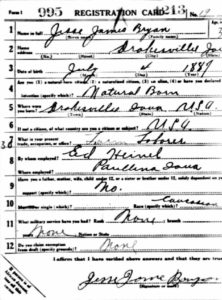

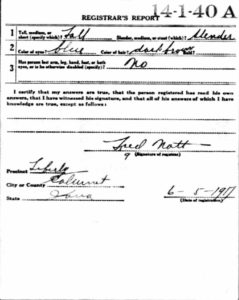

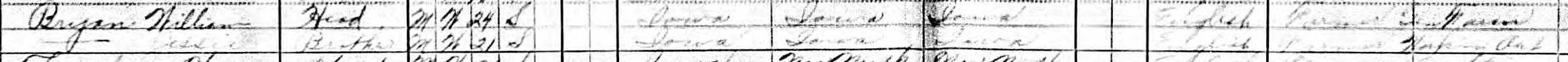

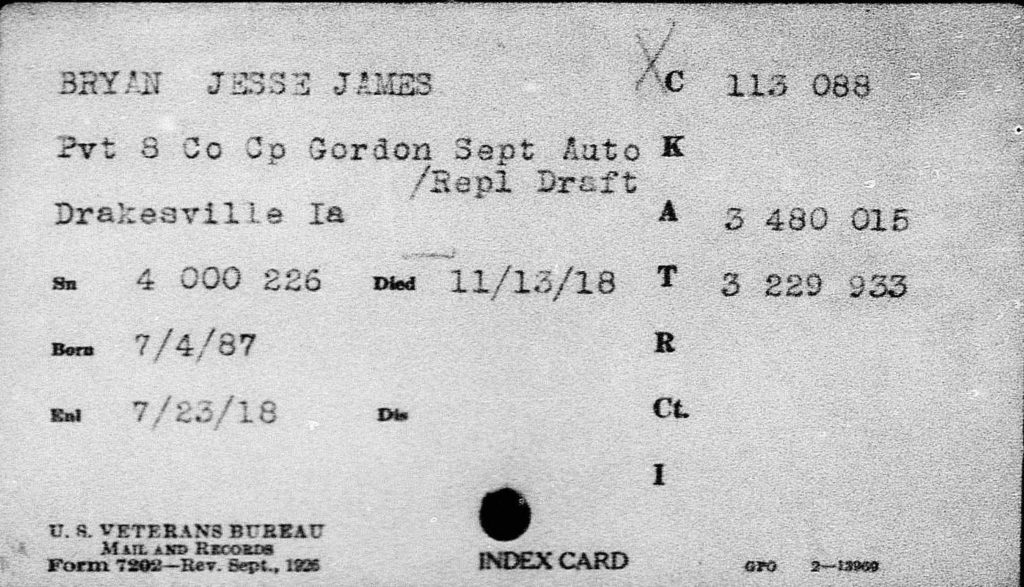

I had intended to continue the story of Jesse J. Bryan today, as part of my series on epidemics and pandemics, but I’m going to go a little sideways with his story and link ice cream with things I’ve stumbled upon while researching WWI and Jesse Bryan. I have mostly searched newspapers in the Atlanta area, because Camp Gordon was located outside Atlanta and Jesse received military training there in late summer 1918.

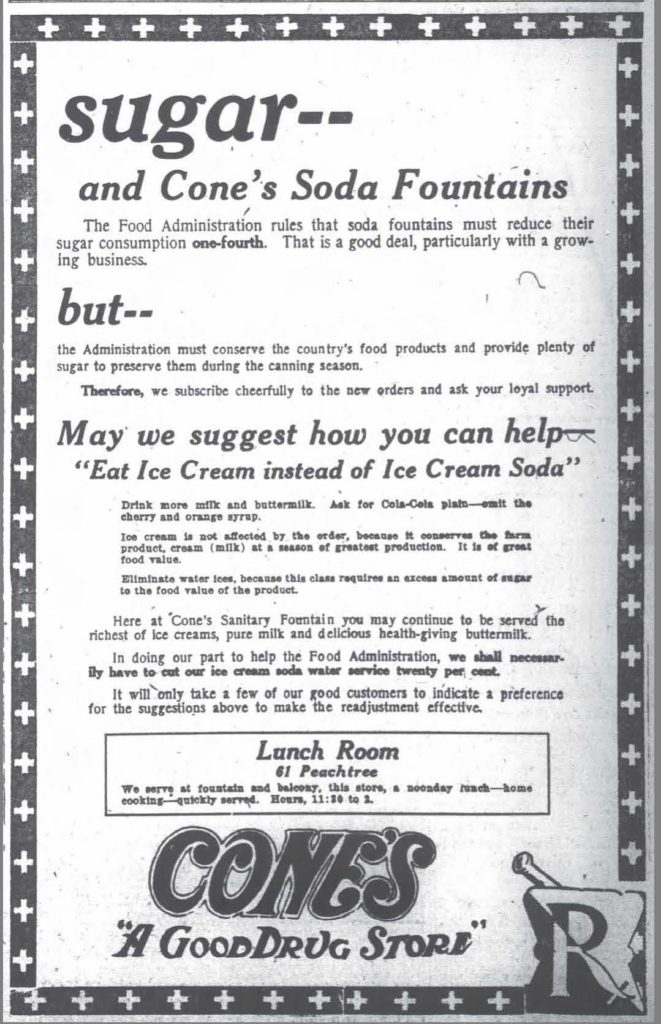

In May, a local drug store asked patrons to order ice cream rather than ice cream sodas to conserve sugar for canning.

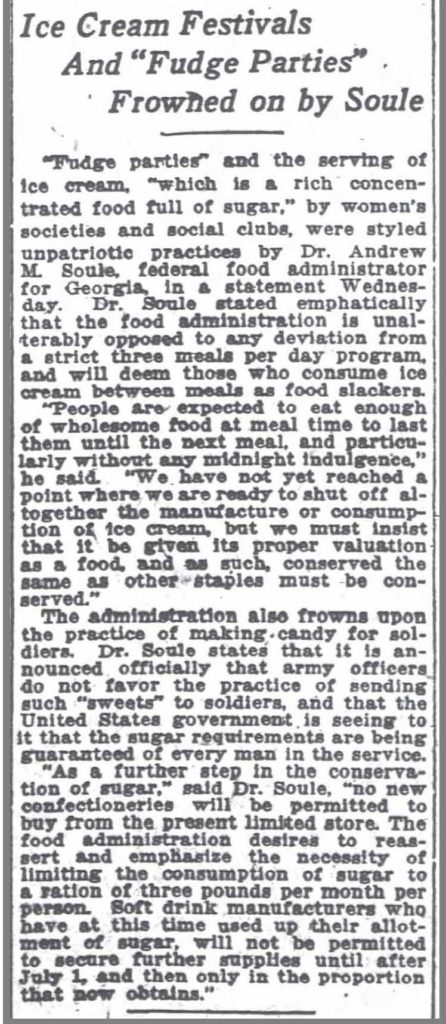

One of the things I have learned recently is that Americans were asked, not only to cut consumption of certain foods, but also to eliminate between meal snacks and to eat only three meals a day. You wouldn’t want to be an unpatriotic “food slacker!”

This did not deter the ladies of the Baptist Church, however.

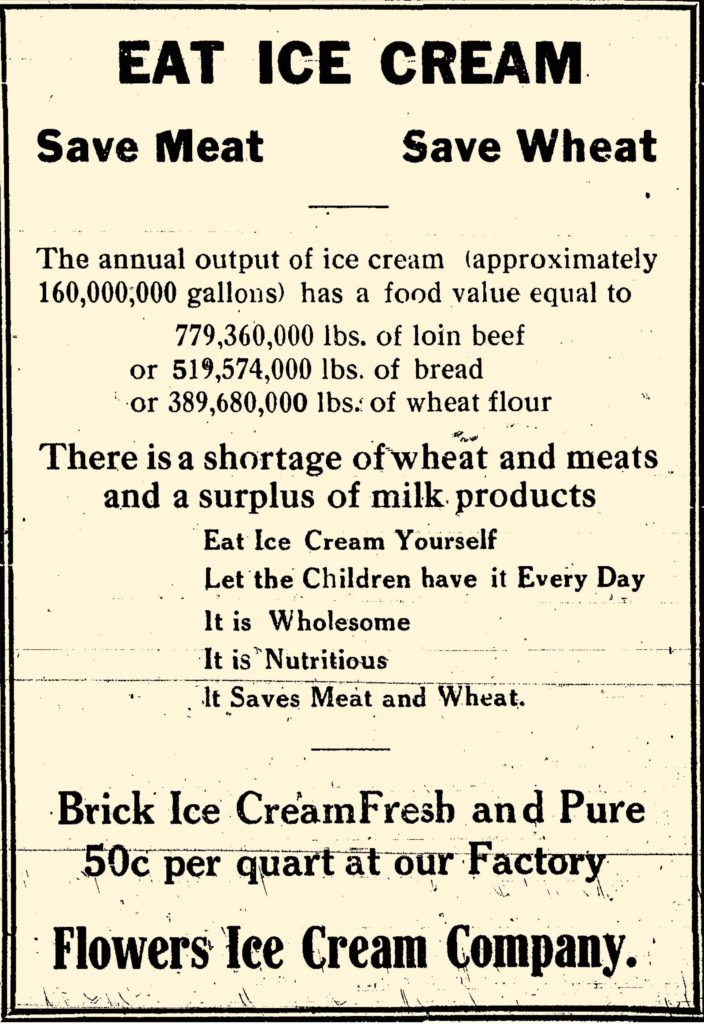

On the other hand, eating ice cream might be more patriotic that eating meat or wheat.

An article in The Atlantic, How Ice Cream Helped America at War, offers this bit of ice cream history:

“An editorial in the May 1918 issue of The Ice Cream Review, a monthly trade magazine, spooned out sharp criticism for the scant availability of ice cream overseas: “If English medical men knew what ours do every hospital would keep ice cream on hand for patients.” It cried for Washington to intervene by subsidizing Allied ice-cream factories throughout Europe:

In this country every medical hospital uses ice cream as a food and doctors would not know how to do without it. But what of our wounded and sick boys in France? Are they to lie in bed wishing for a dish of good old American ice cream? They are up to the present, for ice cream and ices are taboo in France. It clearly is the duty of the Surgeon General or some other officer to demand that a supply be forthcoming.

The ice-cream industry didn’t have much lobbying power. Few Americans had refrigeration. Worse, Hoover had downplayed the scarcity of domestic sugar supplies, hoping to avoid a panic. There was hardly any sugar left for America, let alone for allies in France and England—and the promotion of ice cream as a wartime cure-all wasn’t helping. Instead of bolstering ice cream production, Hoover’s Food Administration ordered a reduction of manufacturing domestically—ruling in the summer of 1918 that “ice cream is no longer considered so essential as to justify the free use of sugar in its manufacture.'”

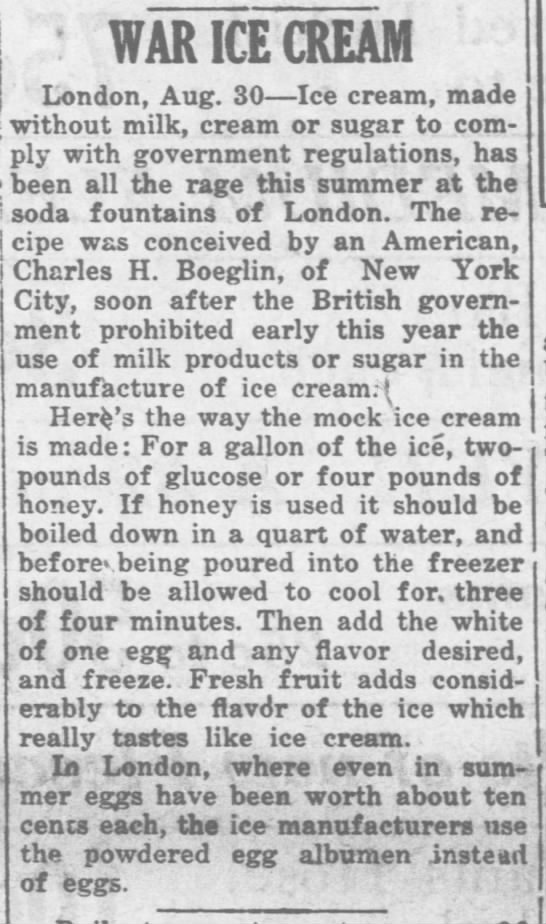

As reported from London, an American devised a recipe for mock ice cream which did not require milk products or sugar.

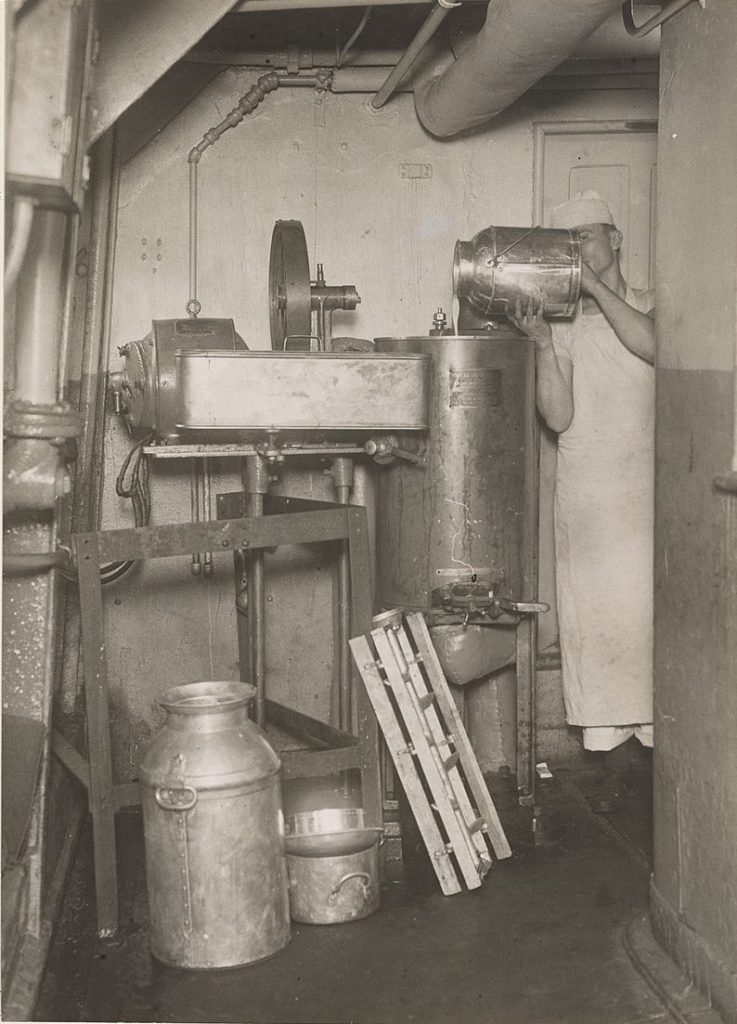

Wounded and ill soldiers on hospital ships apparently had access to the comfort and nutrition provided by ice cream.

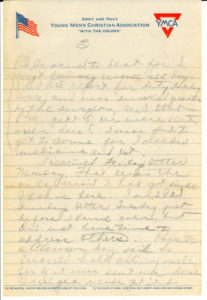

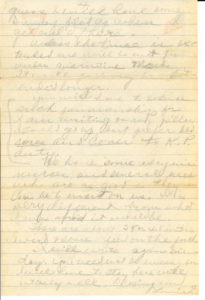

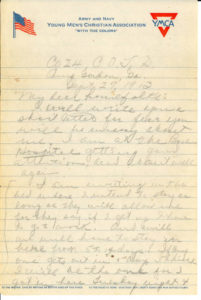

Jesse Bryan was sent to Camp Gordon, Georgia, for his military training. Below is a letter sent from Camp Gordon by Lonnie T. Graham to his family on 17 Sep 1918 – just days after Jesse left Camp Gordon. The letter was accessed from the North Carolina Digital Collection.

I was only going to include the paragraph that references ice cream, but as I read the letter, I wondered if Lonnie had the flu. Influenza hit Camp Gordon mid September 1918. Jesse left on September 3, I think, just missing the outbreak. (I did my best to decipher his handwriting.)

… I am at the Base Hospital getting good attention and about well again.

I am writing in the bed where I intend to stay as long as they will allow me for they say if I get up I have to go to work. And will not will have to stay in here from 5 – 14 days. If any one gets out in 5 days I think I will be the one for I got in here Tuesday night & a square was placed before me Wednesday at dinner. I was so sick at my stomach that I didn’t want anything. But could not refuse such a nice piece of chicken and block Ice cream. The cream was strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate. It wasn’t long before I lost everything. That were’t soup for supper and coffee for breakfast. I got sweet milk from night orderlies. Today at dinner I got another fine meal. I enjoyed the canned cherries more than anything else. Guess they will feed me from now on, as my fever has left me.

I was better Sunday when I wrote. I washed dishes smartly Monday ____ To get some time _____ provided & there had to rub of wind____

I learned to (beat) for I kept feeling worse all day. I didn’t report for duty Tuesday am and was (worked) quarters by the surgeon, and that pm. part of us were sent over here. I was glad to get to come for I needed medicine and rest.

I received Friday’s letter Monday. That was the only mail I had got since I came here. I received Sunday’s letter Tuesday just before I came over, but did not have time to address others. Hester a Cle_son boy said he would hold all my mail, for if it was sent over here I might never get it, so guess I will have some Sunday piled up when I get out of here.

Unless the time is extended we will be out from under quarantine Monday. It will probably be ______ ended longer.

You will have to excuse my penmanship for I am writing on my pillow. I could get up, but prefer bedsores and cover to K. P. duty.

We have some very nice nurses, and several _____ ??h are as good as they can be to wait on us. It is very different from what I was afraid it would be.

There are about 35 or 40 in this ward & some few on the porch.

I will write again Sunday. You need not be worry for I will have to stay here until entirely well. Closing now.

Lonnie

Lonnie just couldn’t resist that block of strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate ice cream even though his stomach was upset. At least it is good to know that the base hospital had ice cream available for the sick soldiers, should they be able to stomach it.

When I was a little girl and had my tonsils removed, I felt very betrayed by the promises of ice cream when it was all over. It tasted like blood. Ice cream did not make it better!

My husband and I find ourselves frequently eating ice cream during the current pandemic. We seem to think it makes us feel better.

There is more information out there regarding the intersection of ice cream and war – especially during WWII, where some pilots devised a way to make ice cream on their fighter planes.

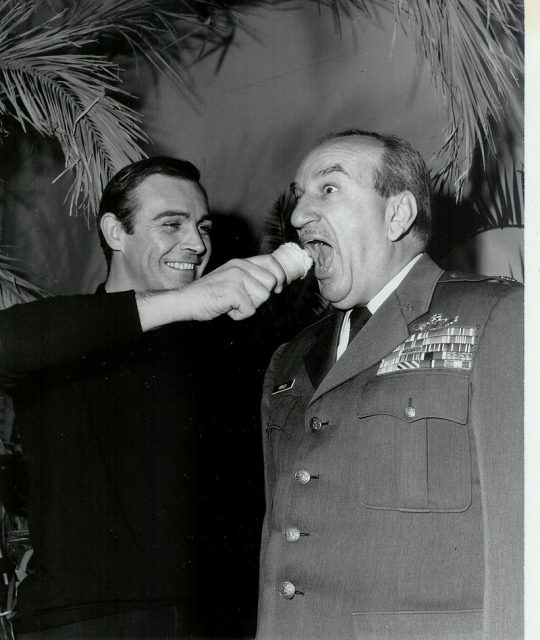

I will close with this photo, which bears some similarity to the prompt photo.

Sean Connery feigns shoving a vanilla ice cream cone in retired Lt. Col. Charles Russhon’s face during the production of “Thunderball”

There must be 32 flavors of ice cream available to those who visit Sepia Saturday . See how others have responded to the prompt photo.