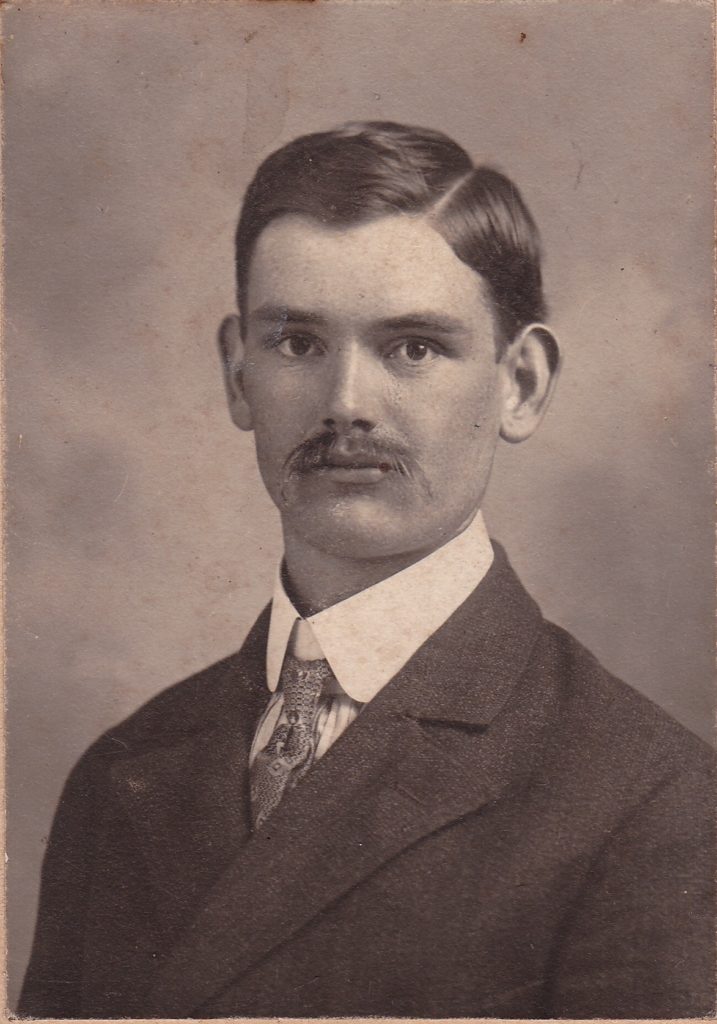

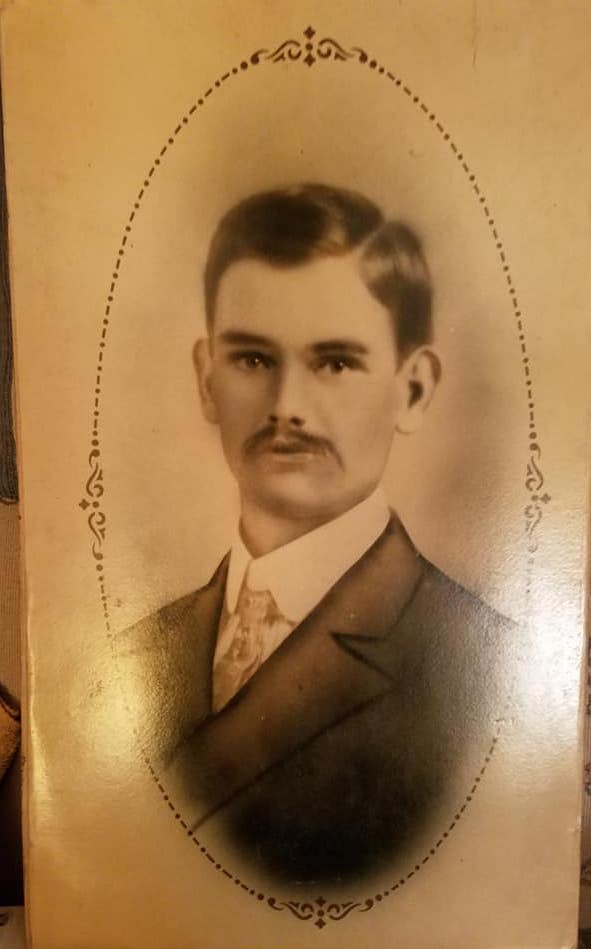

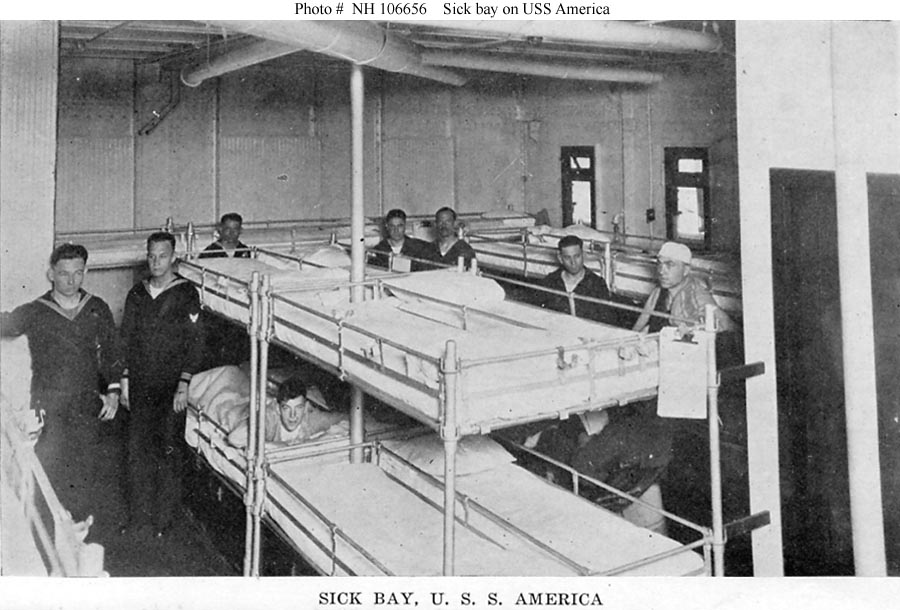

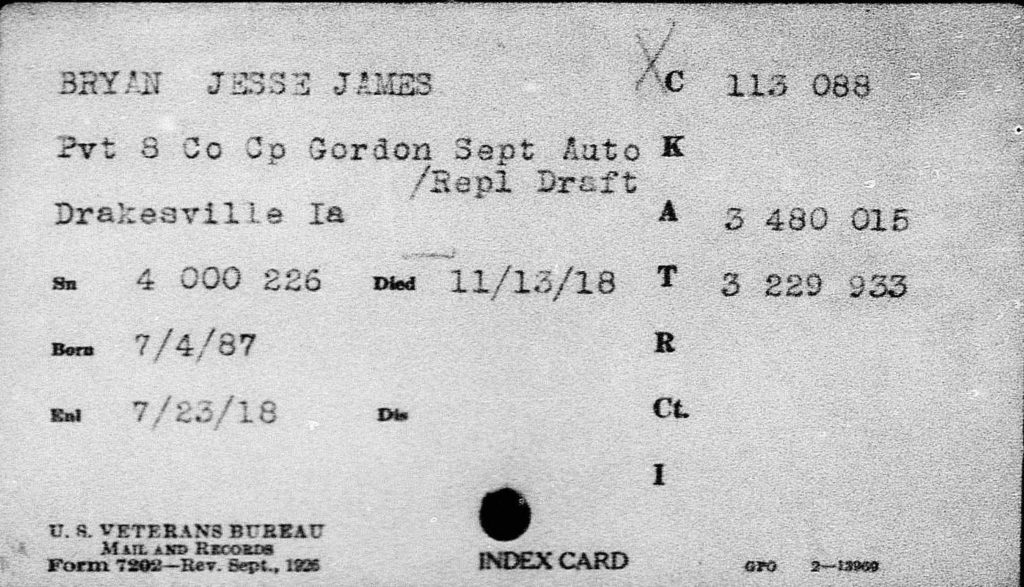

I am continuing a series on how the 1918 influenza epidemic affected my families. The current focus of the series is Jesse James Bryan, first cousin to my grandfather, Thomas Hoskins. I have traced Jesse from his early life in Drakesville, Iowa, to his burial in Brest, France. Jesse Bryan died November 13, 1918 of influenza.

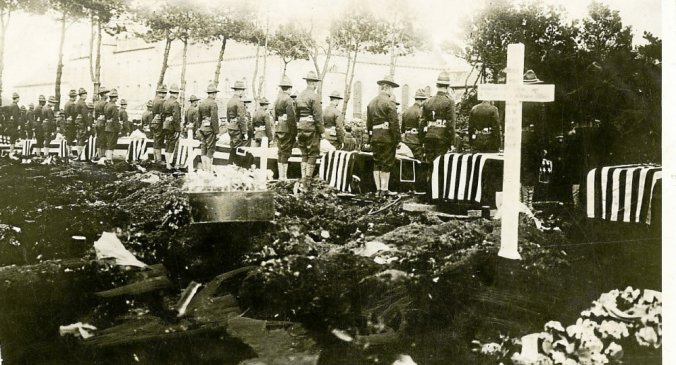

By WW1, Americans had come to expect the return of remains of the war dead to their families, but never before had there been so great a number of casualties on foreign land. This was not the practice in Europe, where the casualties of war usually remained at or near the place of death. These differing points of view led to feelings of ill will between the Americans and the French over the repatriation of American war dead. An early misstep was letters sent by the Adjutant General to families of deceased soldiers that created the expectation that the remains of all American soldiers would ultimately be returned – said without clearing it first with the French government. American soldiers had been buried in temporary graves in cemeteries and in battlefields throughout Europe, the vast majority in France. At the end of the war when the United States wanted to begin the return of the deceased, France had other priorities – food, recovery, their own dead. There were concerns about the additional burden this would place on the transportation system, sanitation, the morale of French citizens, and making allowances for the United States not afforded to other countries. The French withheld permission.

Many in the military agreed that the best thing would be for fallen soldiers to remain where they had died – or in permanent cemeteries for American war dead. But American families had been promised the return of their family member. Lobby groups formed – both for and against the return of American soldiers. A significant shift in American sentiment occurred when former President Theodore Roosevelt expressed a desire for his son’s body to remain where it was originally buried. Thereafter, the War Department decided to poll each family to gauge their desires with respect to the final disposition of their family member. By January 1919, the Secretary of War reported that roughly thirty-one percent of all dead were requested to permanently remain in France. But the situation remained unresolved. The American Legion, General Pershing, Gold Star Mothers, and even funeral directors added their voices to the conversation. It was not until 20 March 1920 that the United States and France finally reached an agreement to permit the repatriation of deceased American troops.

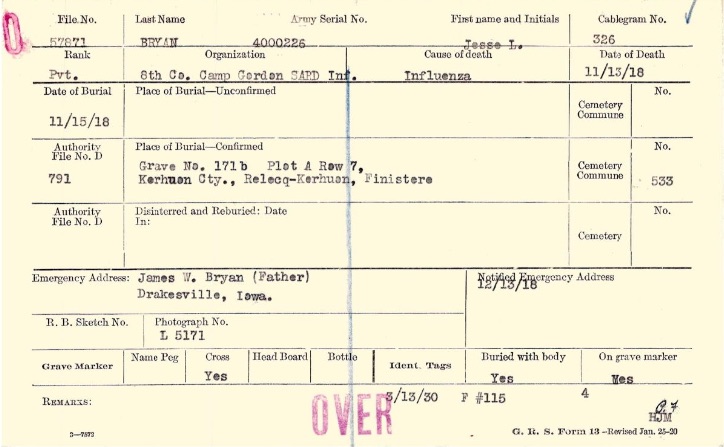

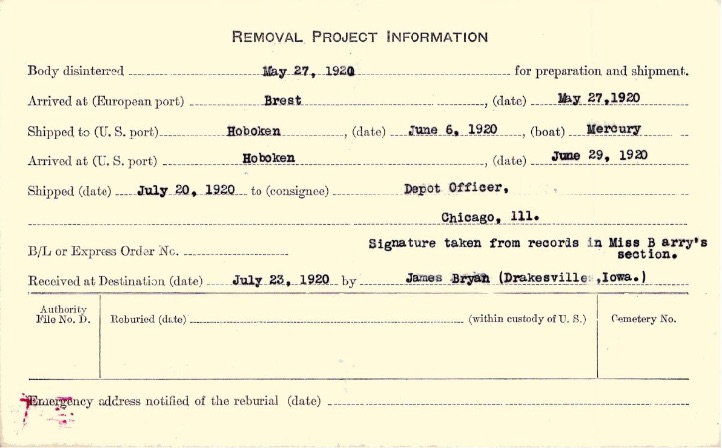

Jesse’s family requested to have his remains returned to his hometown and his family. According to his Grave Registration Card, Jesse’s body arrived in Hoboken on June 29, 1920. The last of the American war dead arrived on American soil March 29, 1922. Jesse’s family did not have to wait nearly as long as many others.

Jesse’s body was disinterred on May 27, 1920. Exhumation procedures followed this general pattern: Workers closed the work area with canvas screens and posted guards to prevent illicit entry. A canvas was laid on the ground next to the exhumation site. Once the coffin was exhumed, the body was removed and placed on the canvas, where it was saturated with disinfectant and deodorant before being wrapped in a blanket. The remains were then placed in a metal casket, encased in pillows to prevent movement, covered with a white sheet, and the casket sealed before being placed in a wooden shipping case. The entire process took less than five minutes. The Grave Registration Service went to great lengths to try to ensure that no mistakes were made in identifying the dead.

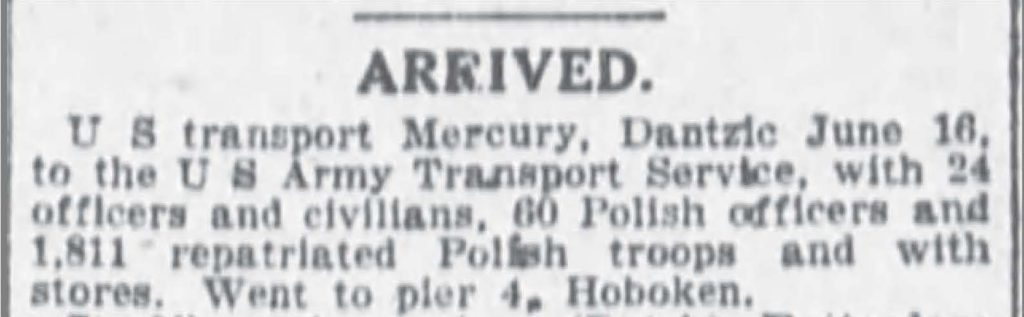

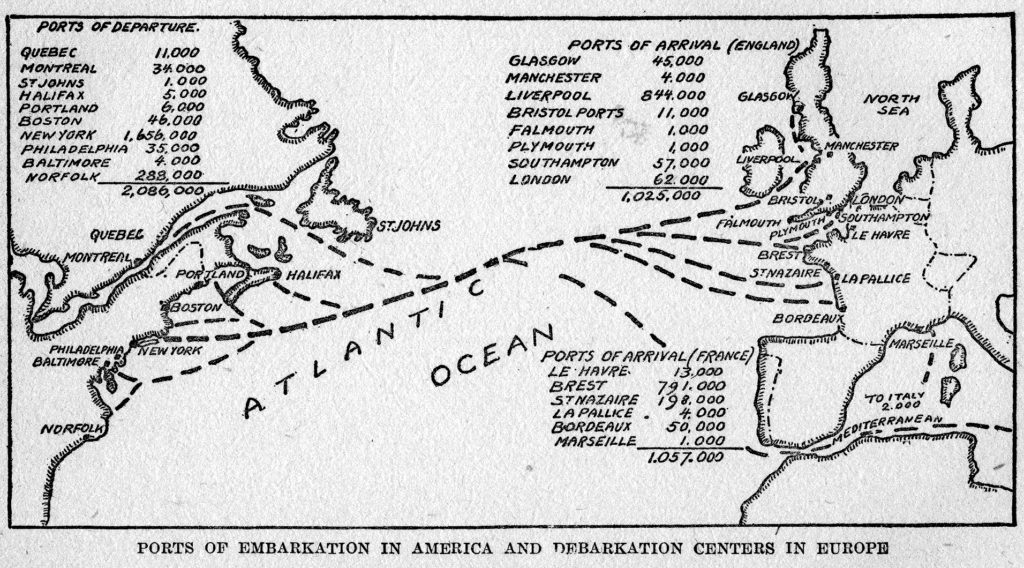

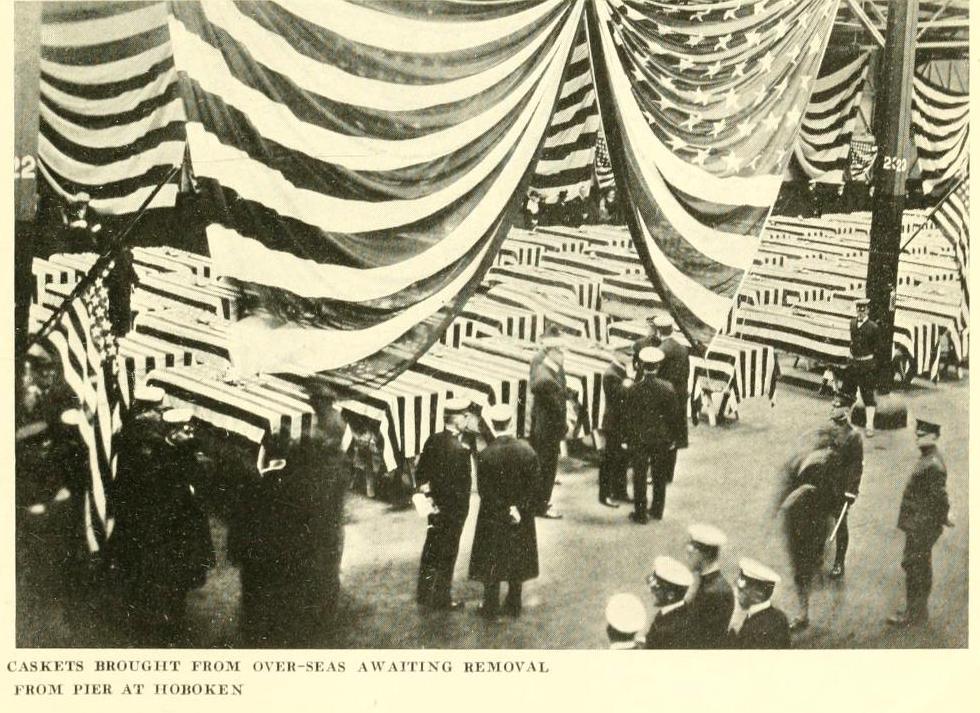

Pier 4 at Hoboken, NJ was selected as the site for the return of transport ships bearing caskets. Once the remains arrived at Hoboken, the Grave Registration Service needed to coordinate the shipment of the caskets to all parts of the United States as quickly as possible. The plan called for the War Department to supply Hoboken with the name of the ship, its deceased passenger list and, if possible, the final destination of each body before the ship docked at the port. This allowed lead time to ensure adequate space at the pier and to arrange ground transportation to the remains’ final destinations.

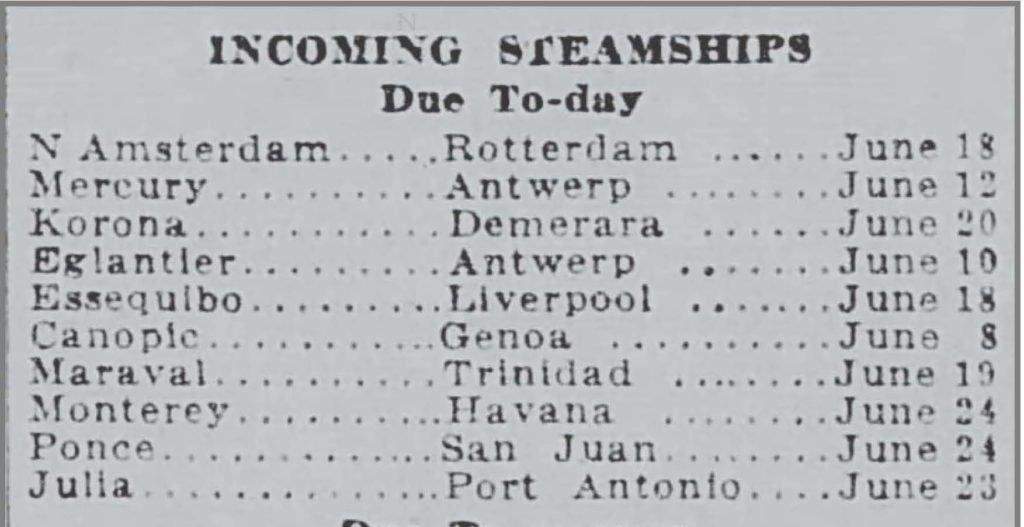

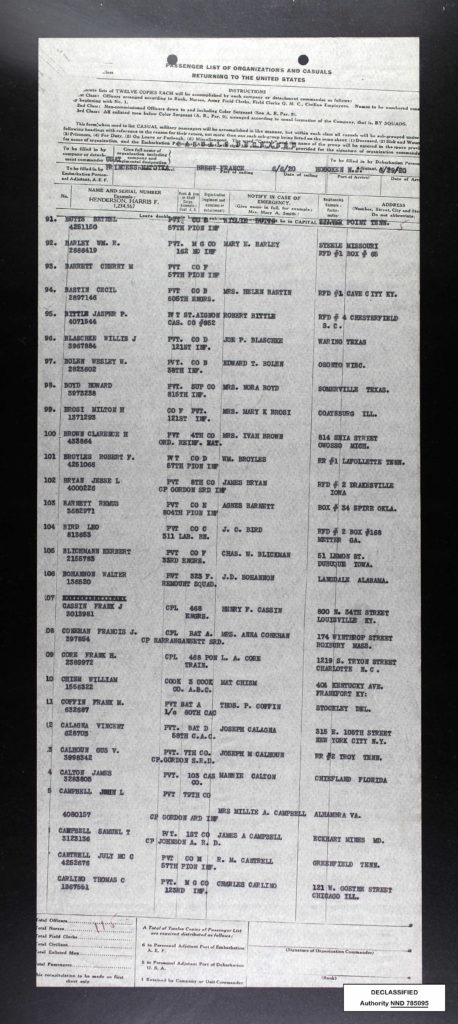

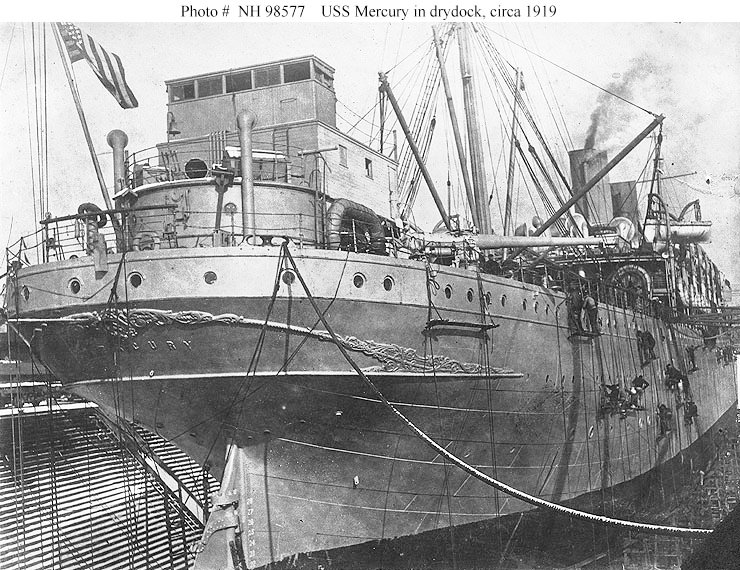

There is a discrepancy between Jesse’s Grave Registration Card and the ship manifest that lists his name. The Grave Registration Card says that his body left Brest June 6, 1920 on the transport ship Mercury. But his name is on a passenger list for the transport ship Princess Motoika.

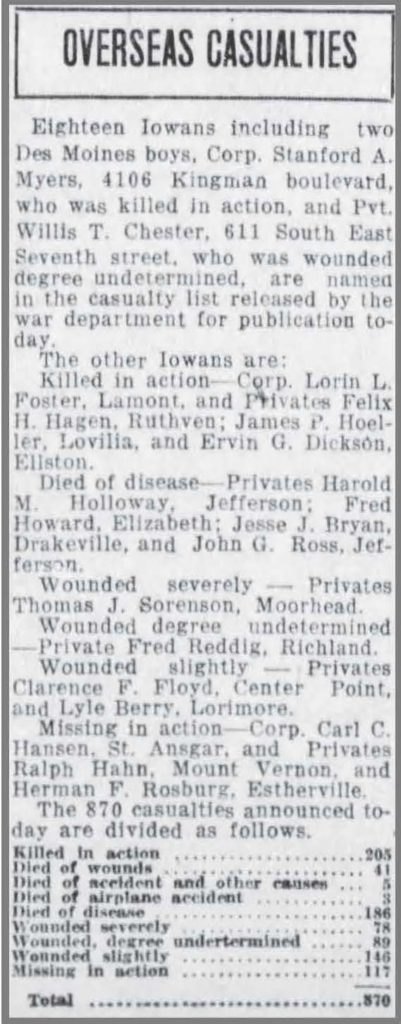

I confirmed the Grave Registration Card with newspaper clippings, but a late night search through all of the pages of the ship’s passenger list revealed that some named the Mercury, while others named the Motoika.

Around this time, the Princess Motoika was chosen to transport the U.S. Olympic team, so this may be the reason for the discrepancy. (The athletes were not at all pleased with their accommodations, by the way.)

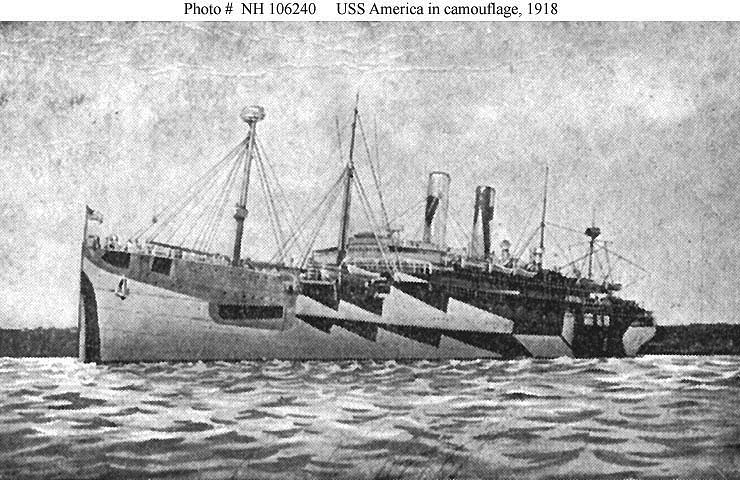

After leaving Brest, the Mercury sailed to Antwerp, Belgium, taking on some passengers, and Danzig, Poland, where a number of Polish troops boarded. The ship carried over eight hundred deceased Americans.

Today, military caskets are always seen draped by the flag of the United States. This idea was born in the aftermath of World War I as officials planned for the movement of remains from the temporary cemeteries to a permanent cemetery in the United States or Europe. Since there were no regulations for this at the end of the war, policies were established as the repatriation of troops progressed. Questions such as the size of the flag and whether or not a flag could be buried with the body were tackled.

After arrival at Hoboken, the Grave Registration Card documents that Jesse’s remains were shipped to the Depot Officer in Chicago on July 20. He finally arrived at Drakesville, Iowa on July 23, 1920 to be received by his father, James Bryan.

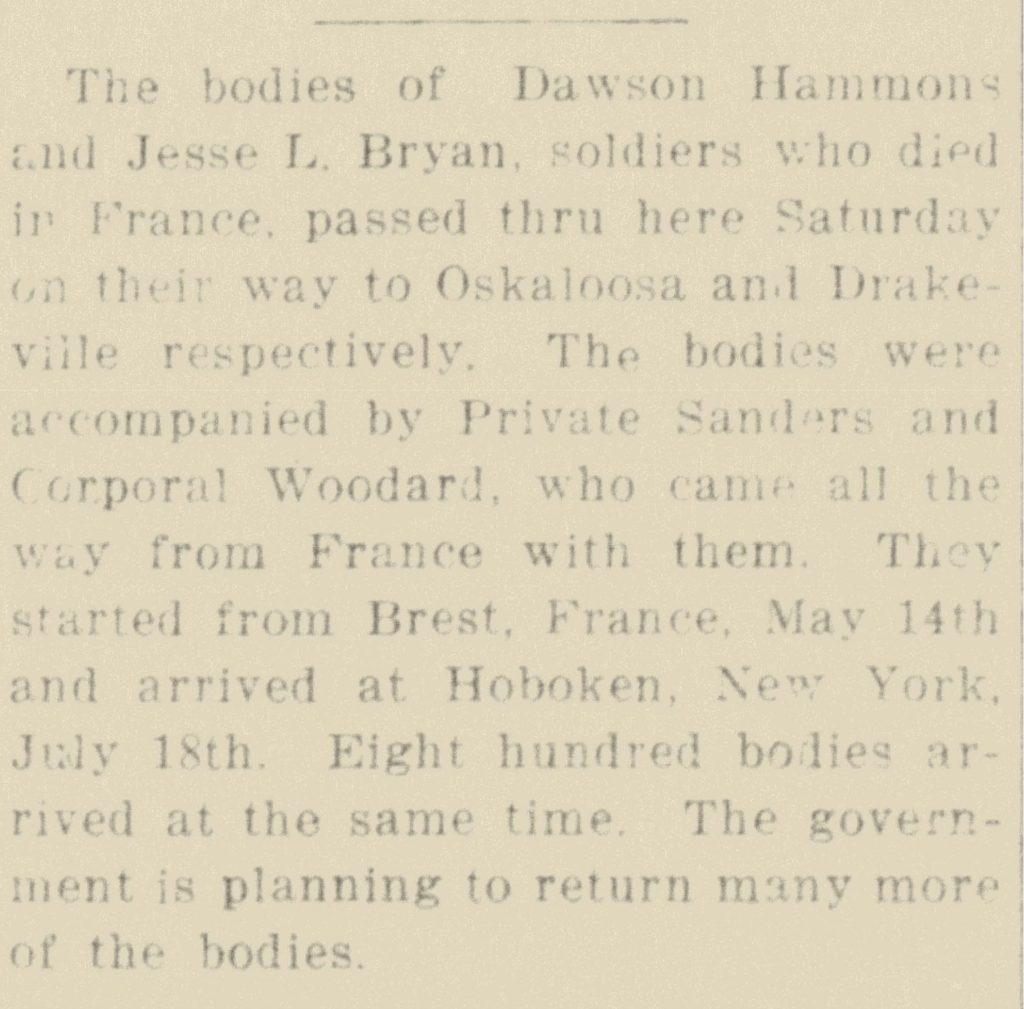

When the remains departed Hoboken for their final destination, a military escort accompanied each casket. Nearby Fort Hamilton, New York, usually furnished the necessary soldiers for this detail. Escorting military remains was another practice begun as a result of WW1 that the military has continued to use. The military escort accompanying remains to a funeral might be the only personal interaction some citizens had with the Army. The idea of a military escort was also practical. When a casket was shipped by train, it required documentation, just like any other cargo. In addition, as the casket changed possession receipts were required to be obtained and forwarded to the Office of the Quartermaster General. The escorts helped train station agents and funeral directors, particularly those of small towns, navigate unfamiliar government paperwork, ensure that the casket was delivered in good order, and obtain proof of receipt by the family or appointed representative. The escorts also assisted the funeral director with moving the casket to and from the funeral home, into homes, churches, and ultimately the burial site.

The newspaper clipping below reports that the military escort accompanied Jesse’s body from France, which is different from what I read was the usual situation. The dates don’t exactly match up either.

Hattie Bryan, Jesse’s youngest sister, told her granddaughter that she remembered the soldiers coming to the door of their home to report Jesse’s arrival and their attendance at the funeral. Hattie’s granddaughter has the flag that was draped on Jesse’s coffin.

I received these copies of newspaper clippings from the Davis County, IA Historical Society.

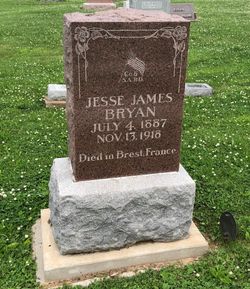

Jesse Bryan’s final resting place – Drakesville Cemetery, Drakesville, Iowa.

JESSE JAMES

BRYAN

JULY 4, 1887

NOV. 13, 1918

Died in Brest, France

This concludes my research into the life and death of Jesse James (Joe) Bryan – unless I can eventually get military records or some letters turn up.

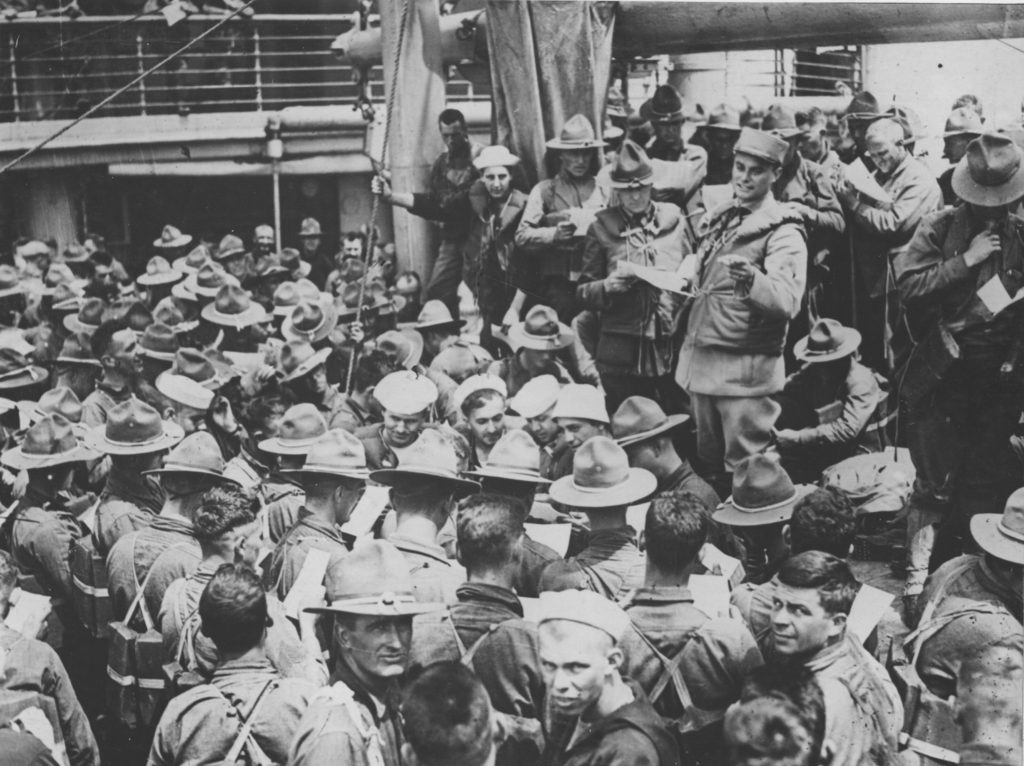

Jesse was drafted into the army to fight in France, trained for combat as the influenza virus reached pandemic status, was infected on the transport ship as he approached France, and died at the age of thirty-one – two days after the Armistice was signed.

I recently received these two photos from the great-granddaughter of Hattie Bryan. The woman is Jesse’s youngest sister Hattie – the little girl who only remembered meeting her brother when he came home on furlough before his departure for France and who remembered the military escorts coming to her home.

When I started researching Jesse’s life, I thought I’d just write two or three posts and be done. But there were puzzles to solve and the more I researched, the more interested I became in understanding the context of the pandemic and the military experience.

A few weeks ago, I found a video from the National WW 1 Museum, a lecture titled Forgetting a Catastrophe: Influenza and the War in 1919. It is forty minutes long and I had no intention of watching all of it – I was just curious to see what it was. I watched the whole thing. There is a lot of interesting information here, but Professor Nancy Bristow’s main point is that the influenza pandemic was essentially forgotten. Although more lives were lost to influenza than to the war, there are very few memorials – or even mentions in popular culture. The professor believes that we Americans like to ignore or rewrite the bad parts of our history and focus instead on progress, success, and victories. This keeps us, she says, from thinking deeply and voices of trauma are drowned out. She ended her talk (in January 2020) by saying that pandemics are a thing of the future and that admitting our tales of sorrow and loss is important – ironically unaware of how soon that future would be. Here we are.

When I asked my extended family for any stories of how the influenza pandemic affected our families, I got only two replies. Surely there could have been more.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, I hope we will think deeply and not hurry too quickly to move on and “get back to normal”. I hope the voices of trauma will be heard and remembered. I hope we will tell our stories. I hope lessons learned will not be forgotten. I hope that we do not forget that our ideas of who or what is “essential” changed.

And given the events of this week, I have the same thoughts about January 6, 2021. We need to engage in deep thinking.

*****A source I used for a lot of the information in this post can be found here: Establishing the American way of Death: World War I and the Foundation of the United States Policy toward the Repatriation and Burial of its Battlefield Dead.

*** I have made a landing page where all of the posts related to epidemics and pandemics are collected. Epidemics and My Families

Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

Please hop on a tram, train, truck, or transport to visit others who participated in Sepia Saturday.