Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.

As I was researching material for last week’s post, I found too much to include. I intended today’s post to be about an event later in my great-uncle Fred M. Webber’s life, but this prompt also works for some of that high school material I found.

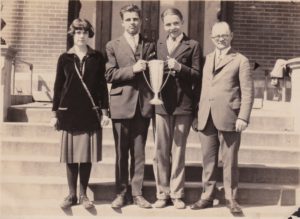

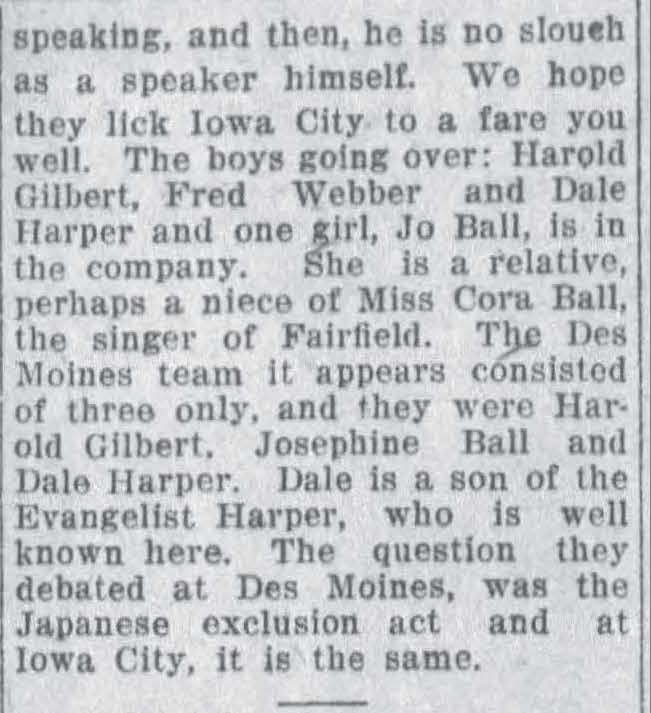

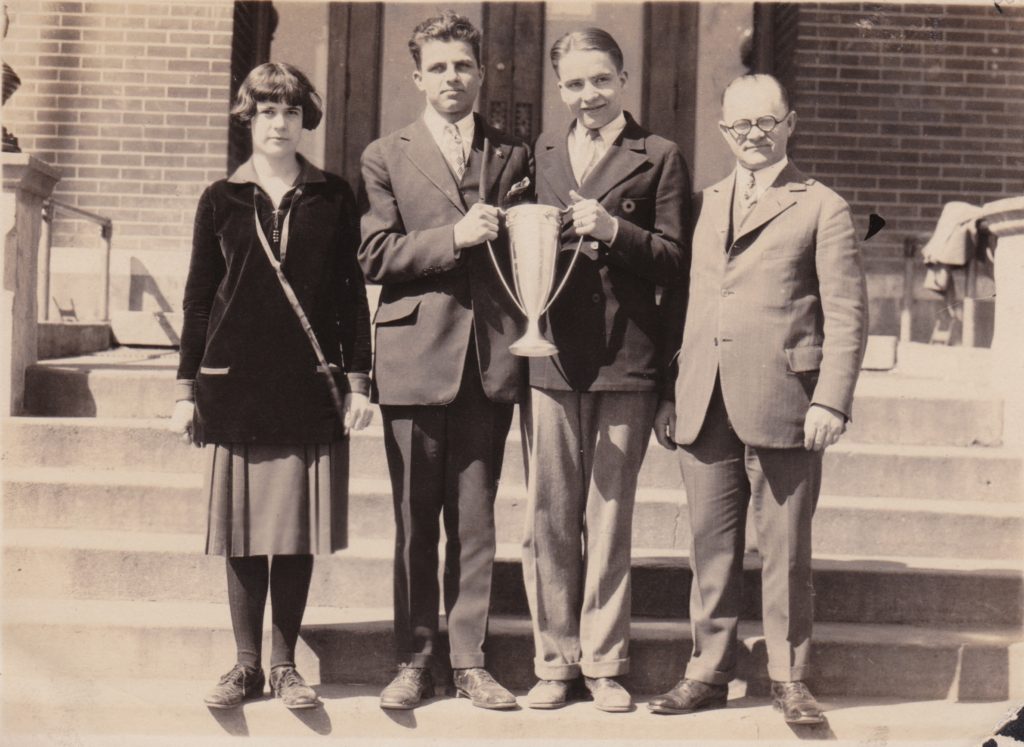

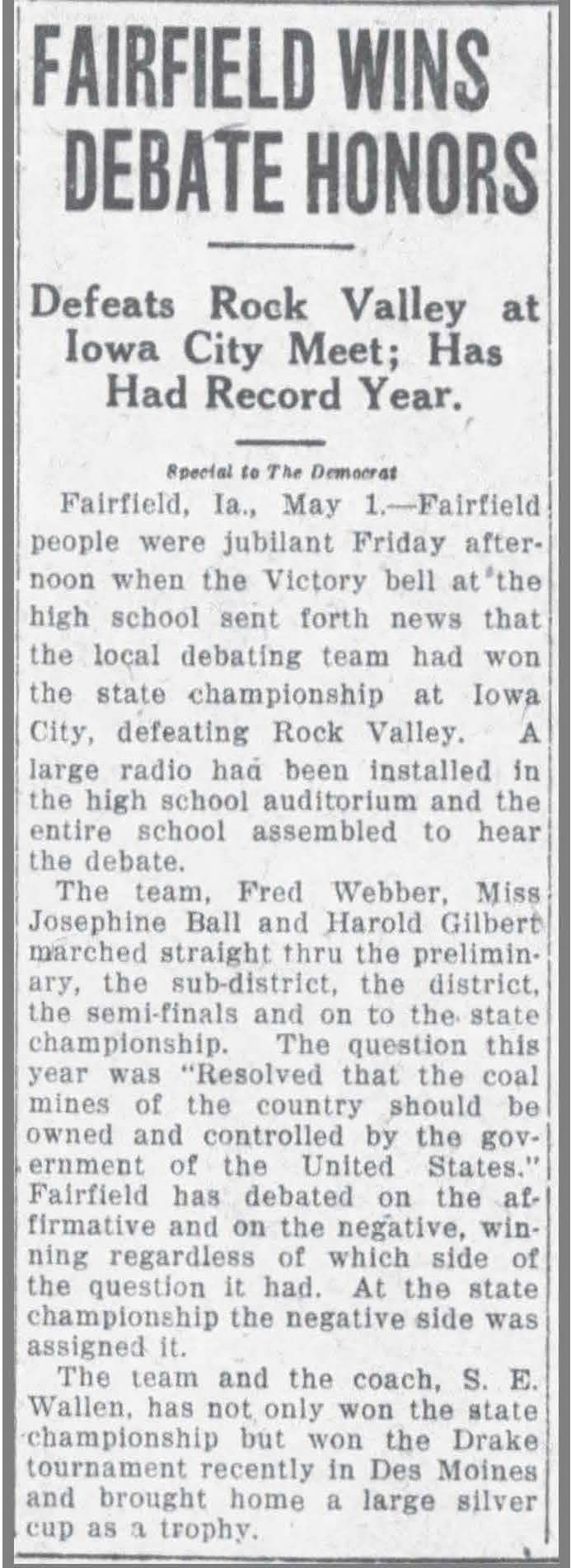

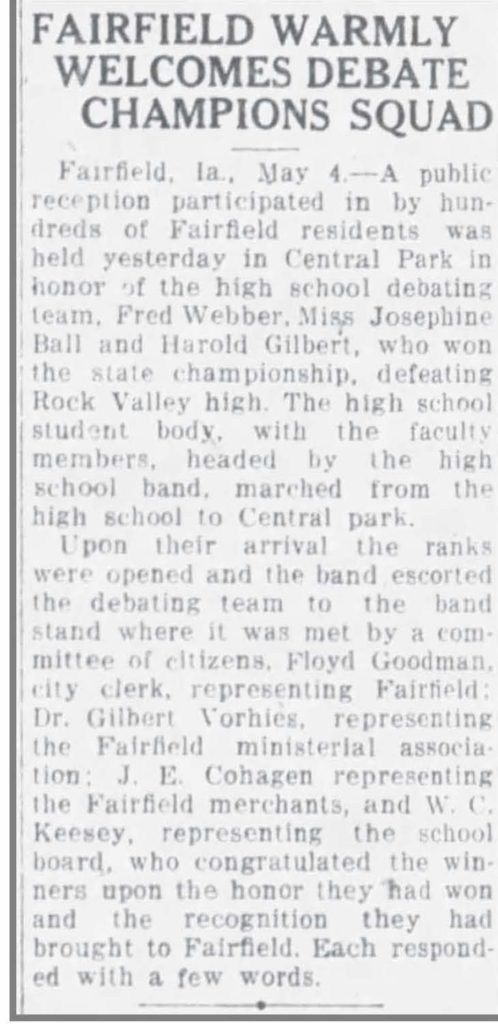

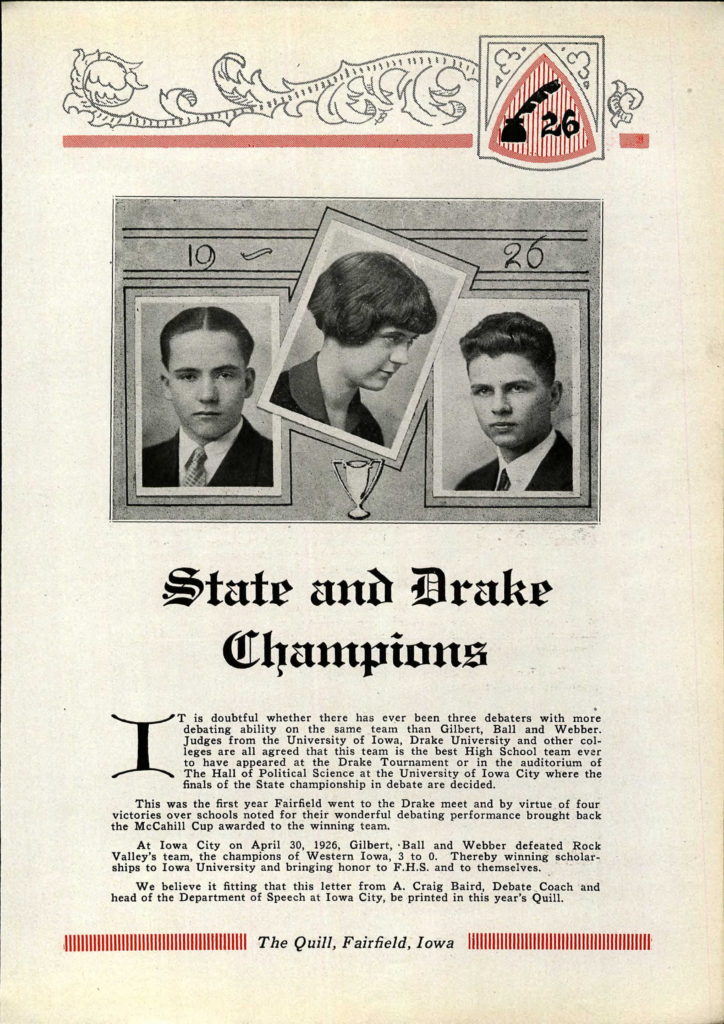

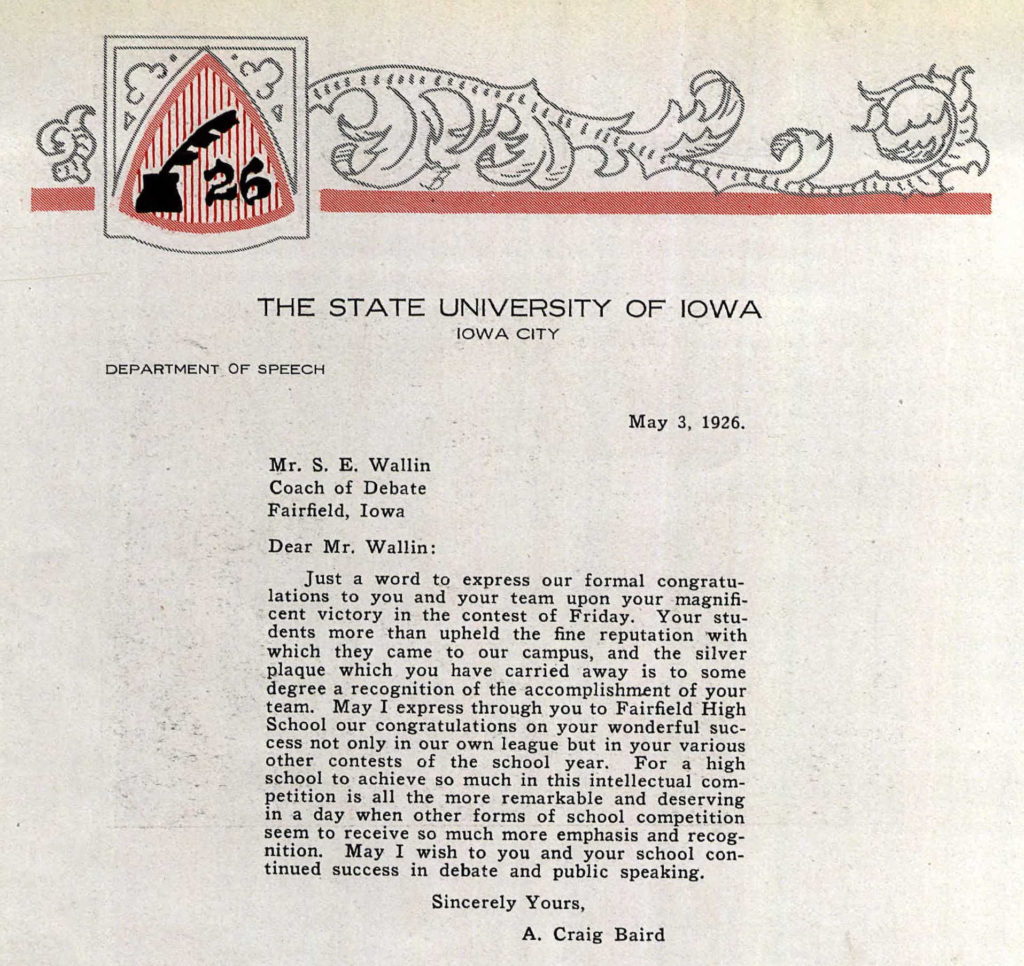

Last week I focussed on Fred’s participation in debate and winning the state championship during his senior year. (Fred Webber – Best Debater 1926) This week, we may get a more rounded look at Uncle Fred as a high school student. The Quill, yearbook of Fairfield High School, Fairfield, Iowa, had a few things to say about Fred Webber.

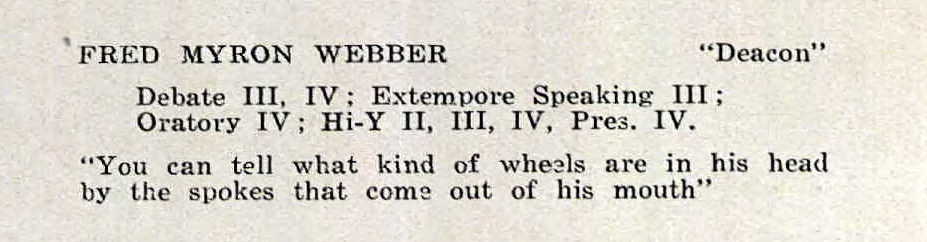

1926 was Fred’s senior year of high school and the yearbook is filled with little tidbits about the seniors. Each senior’s portrait is accompanied by a list of activities and organizations, a quote that the editors thought summed up the student, and a nickname.

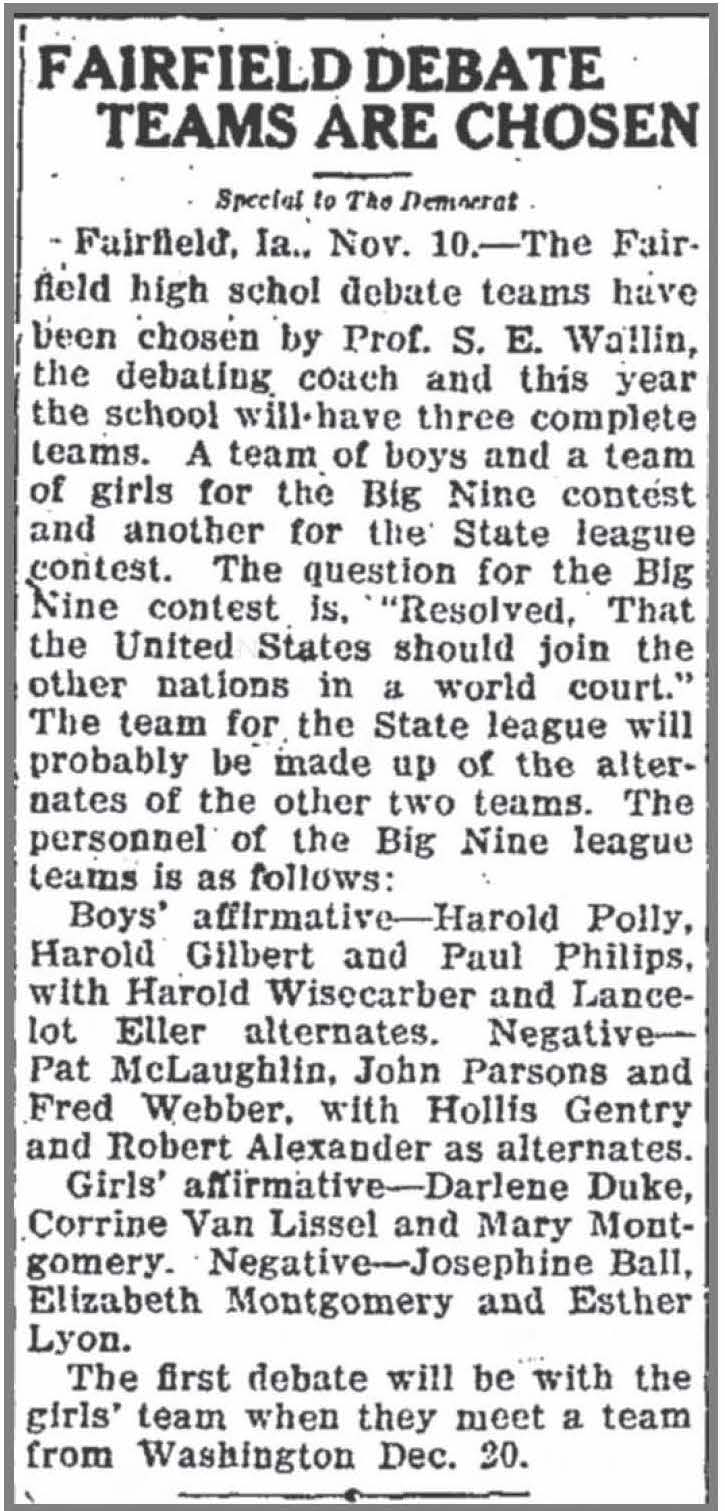

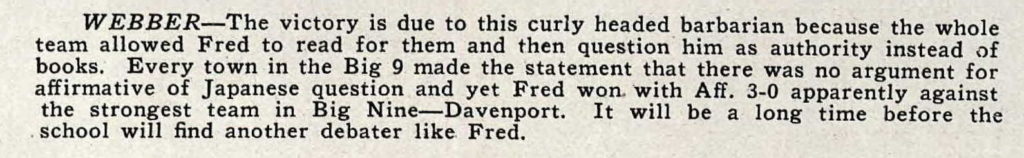

Debate: I wrote at length about Fred’s participation in debate last week, but there were more little details in the yearbook than those I included. One debate page was devoted to the Affirmative Big Nine team and had this to say about Fred, the “curly headed barbarian.” The Japanese question was: “Resolved, that the Japanese Exclusion Act should be repealed in favor of a gentleman’s agreement.”

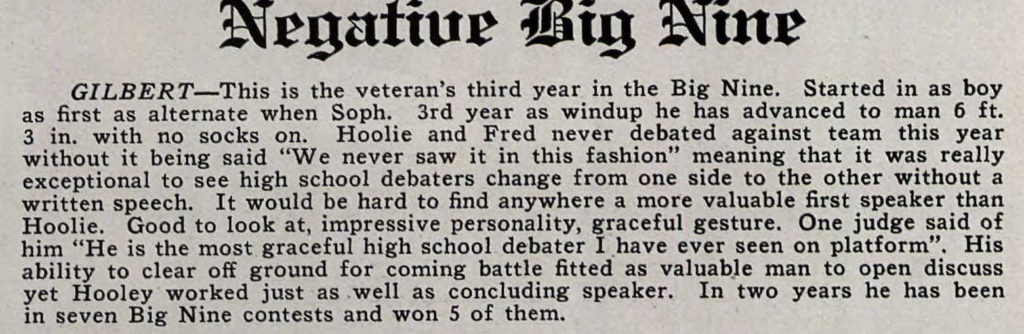

On the page devoted to the Negative Big Nine team, Fred is even mentioned in the item written about his teammate Harold Gilbert.

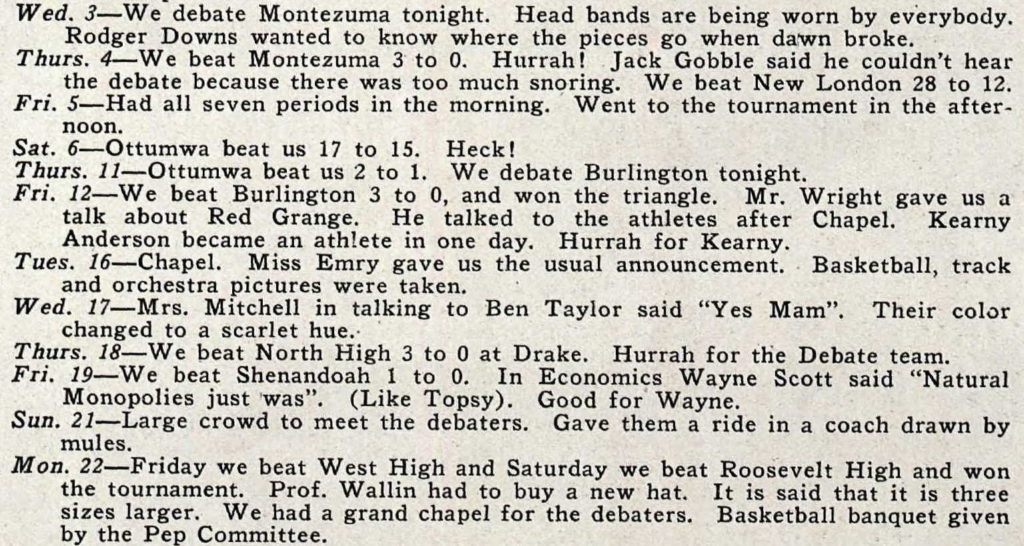

The calendar pages in the yearbook are fun.

March was a busy month for debate. Students apparently wore headbands in support of the debate team. And I love the last entry about the debate coach.

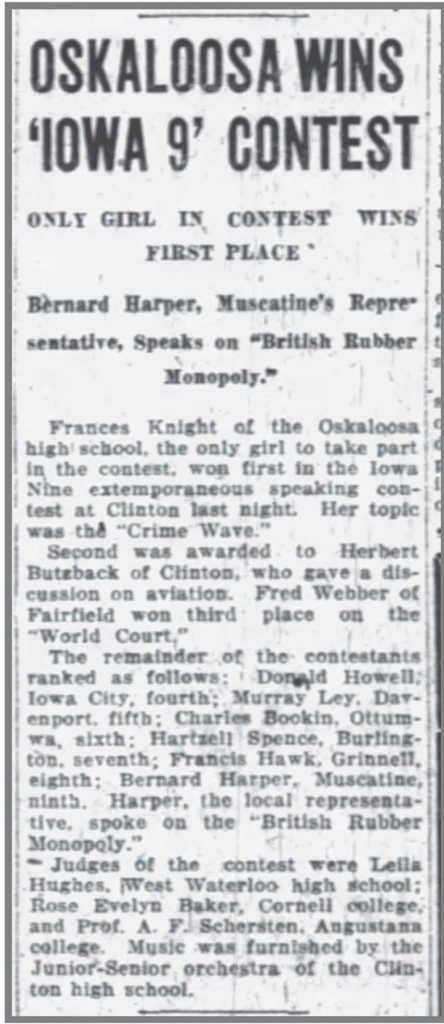

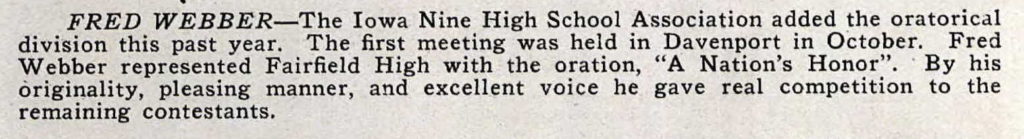

Extempore Speaking: Fred came in third place, speaking on the “World Court.”

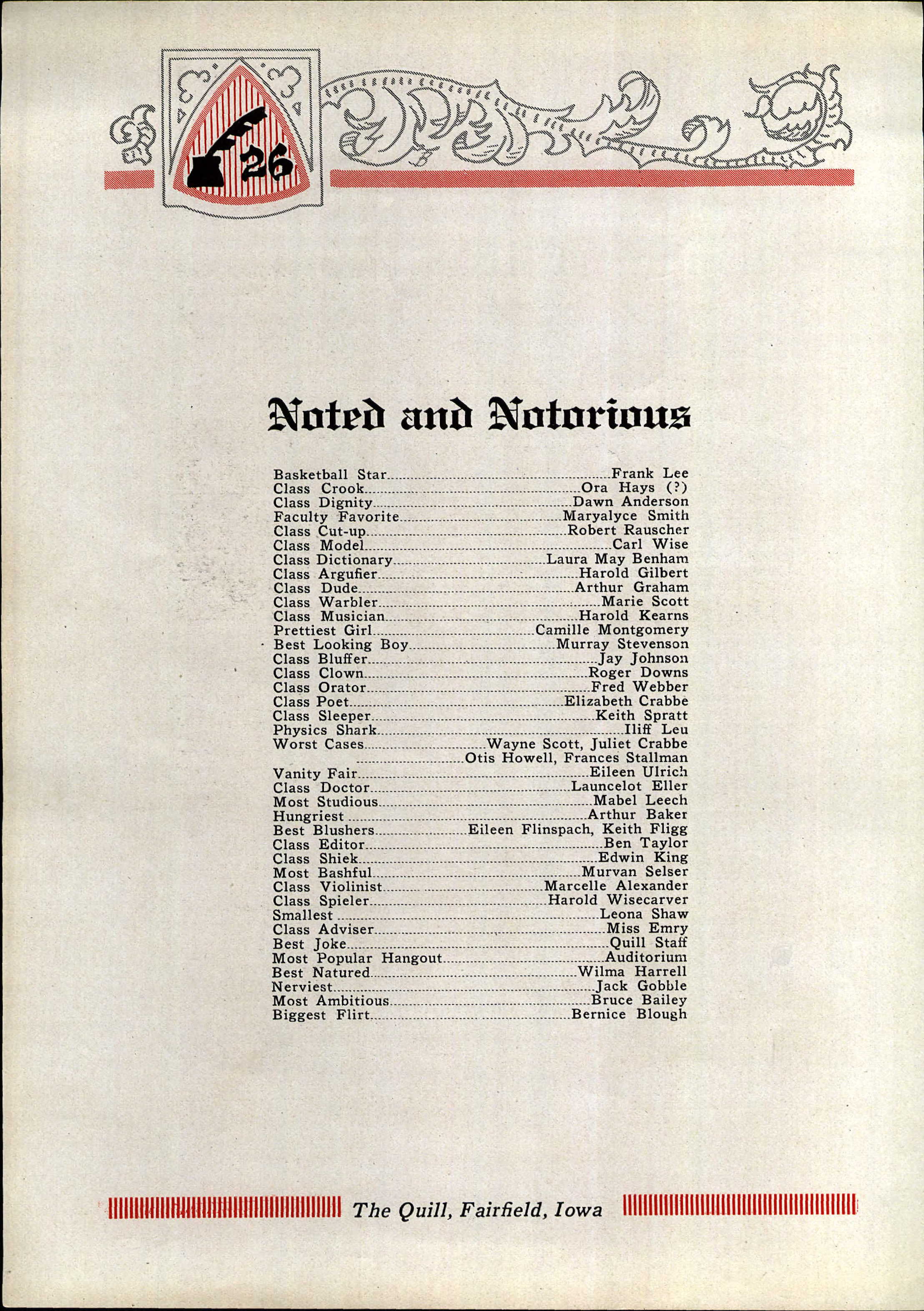

Oratory: In addition to participating in Oratory during his senior year, here is Fred on the page titled “Noted and Notorious,” sandwiched between Class Bluffer, Class Clown, Class Poet, and Class Sleeper. The Quill staff designated Fred as Class Orator.

On the page devoted to “Declamatory,” Fred’s picture, along with two female students who did dramatic readings in other contests, is featured along with this description.

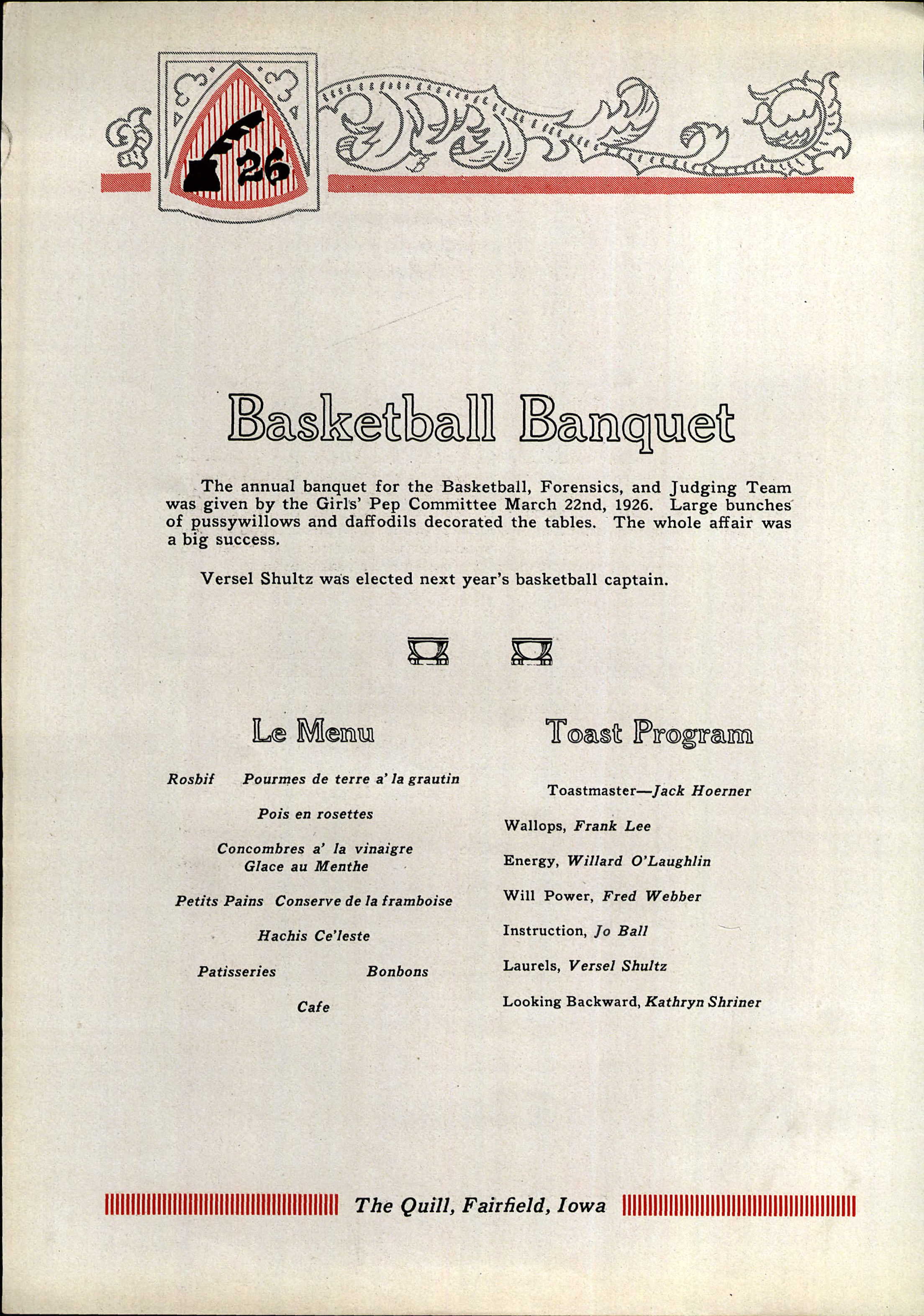

In March, Fred was one of the speakers at the Basketball Banquet. I thought that a little odd since Fred didn’t participate in sports, but on closer look, the “Basketball Banquet” was actually for the Basketball, Forensics and Judging Team. A little curious that they were lumped together. Maybe there was not usually a banquet for the debaters, but the State Champions deserved a banquet as much as the basketball team did. Fred spoke on the topic “Will Power.”

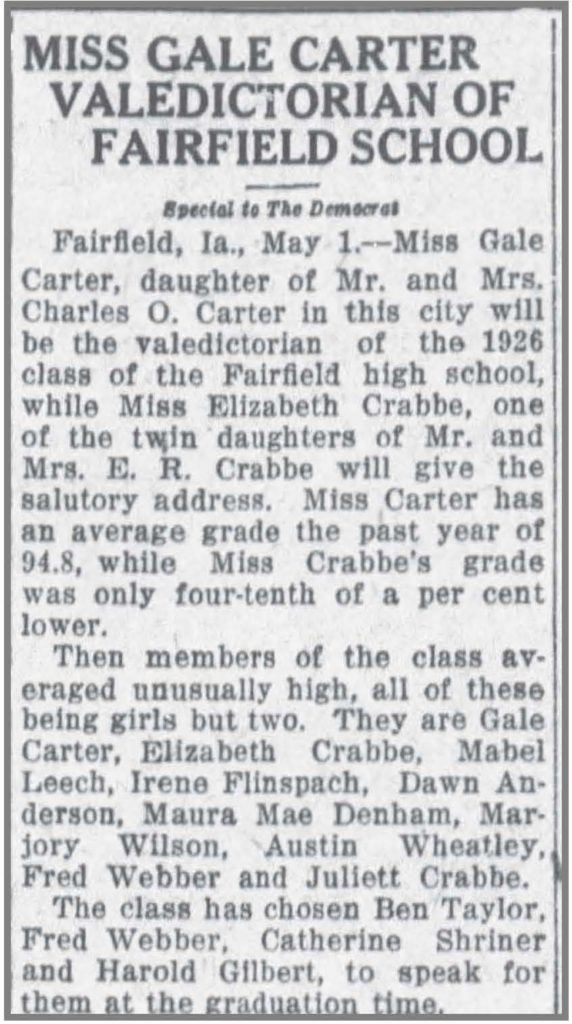

The Senior class chose Fred to be one of the speakers at graduation.

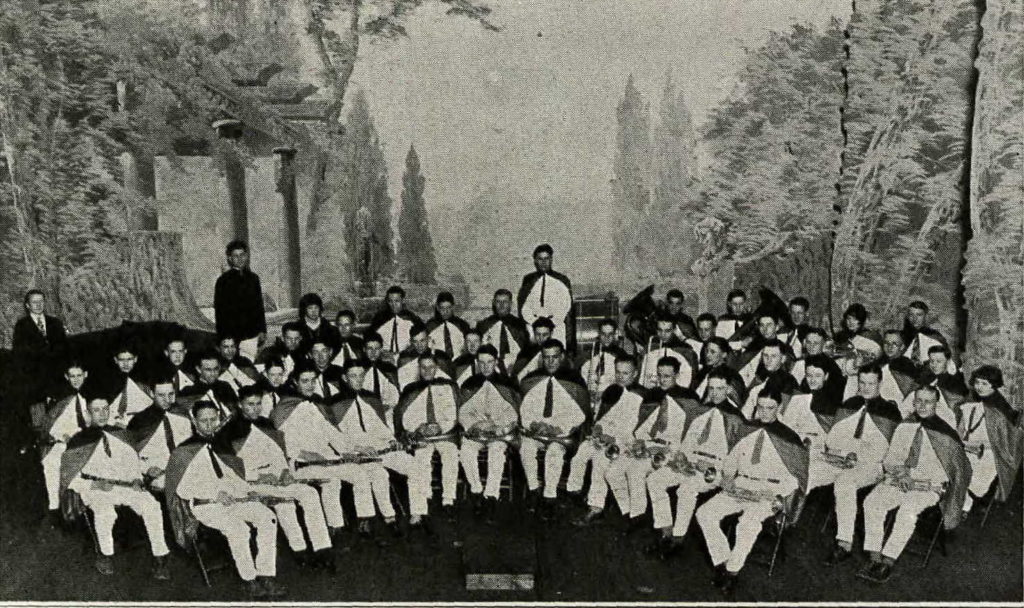

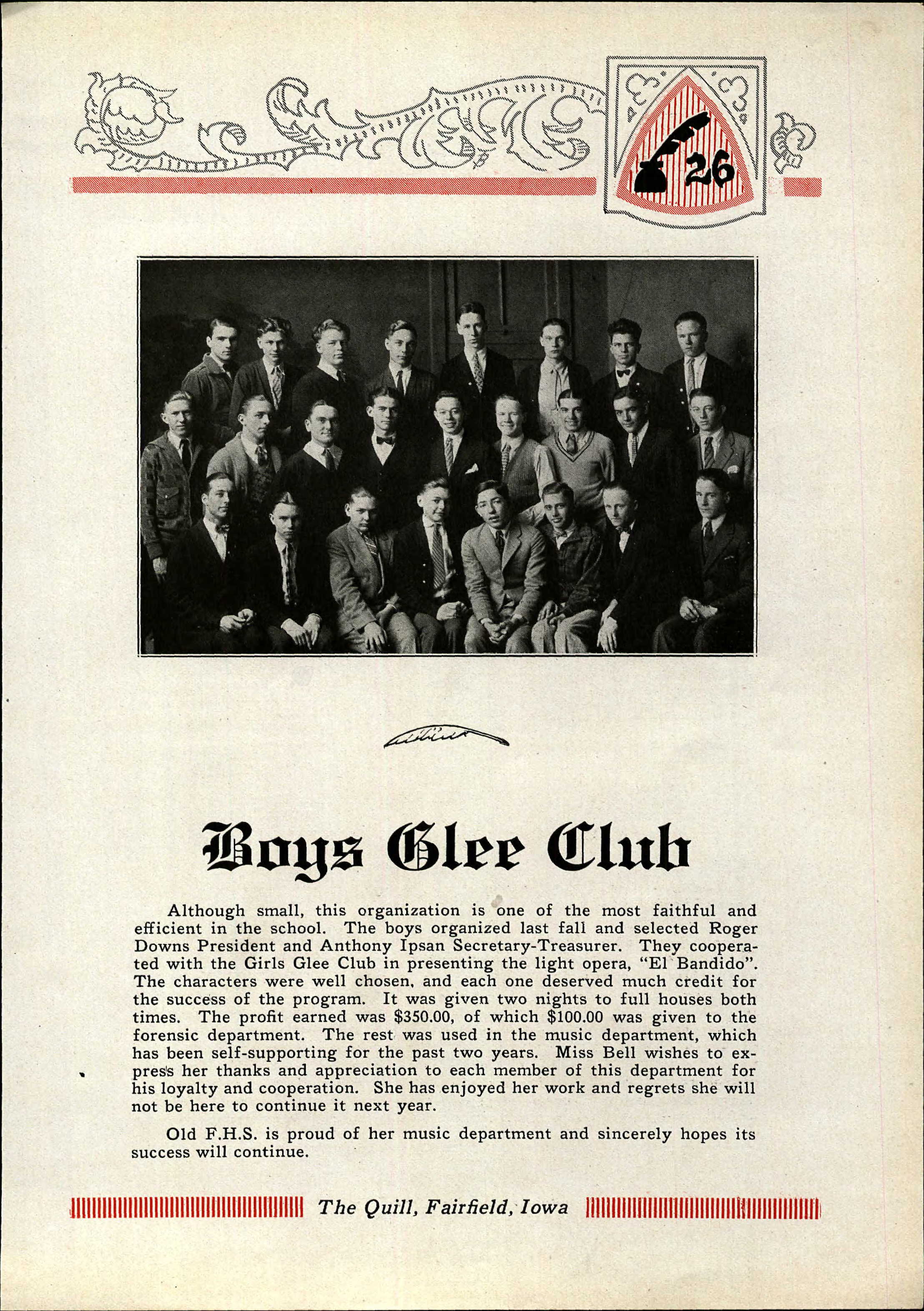

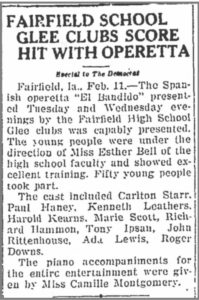

Glee Club is not listed among Fred’s school activities, yet here he is on the Glee Club page, back row, second from right.

I tried to find more about this Spanish operetta, but all I found were newspaper articles announcing various high schools around the country performing it. “El Bandido” must have been all the rage.

I tried to find more about this Spanish operetta, but all I found were newspaper articles announcing various high schools around the country performing it. “El Bandido” must have been all the rage.

Uncle Fred isn’t mentioned in the local paper as part of the cast, so maybe he was in the chorus.

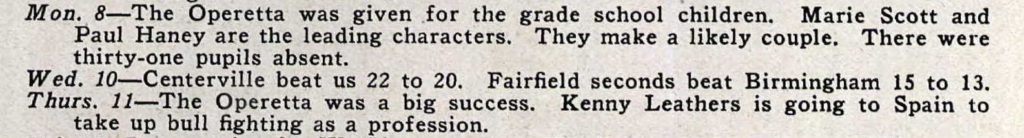

The calendar page of the yearbook:

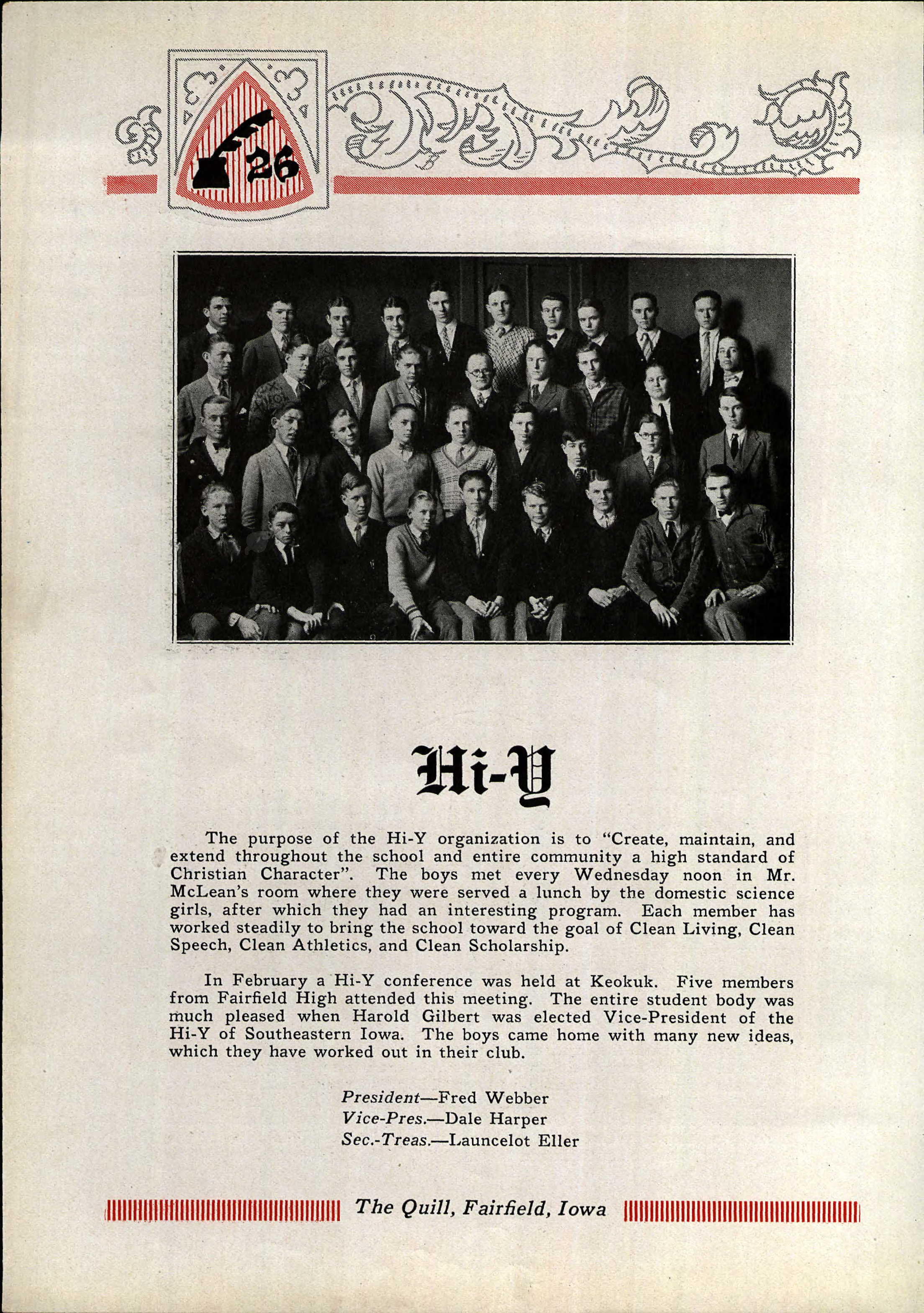

Hi-Y: During his senior year, Fred was president of his high school Hi-Y, a Christian organization working to bring the school toward the goal of “Clean Living, Clean Speech, Clean Athletics, and Clean Scholarship.” He doesn’t seem to be in the photo below. The debate coach, S. E. Walllin was the faculty sponsor.

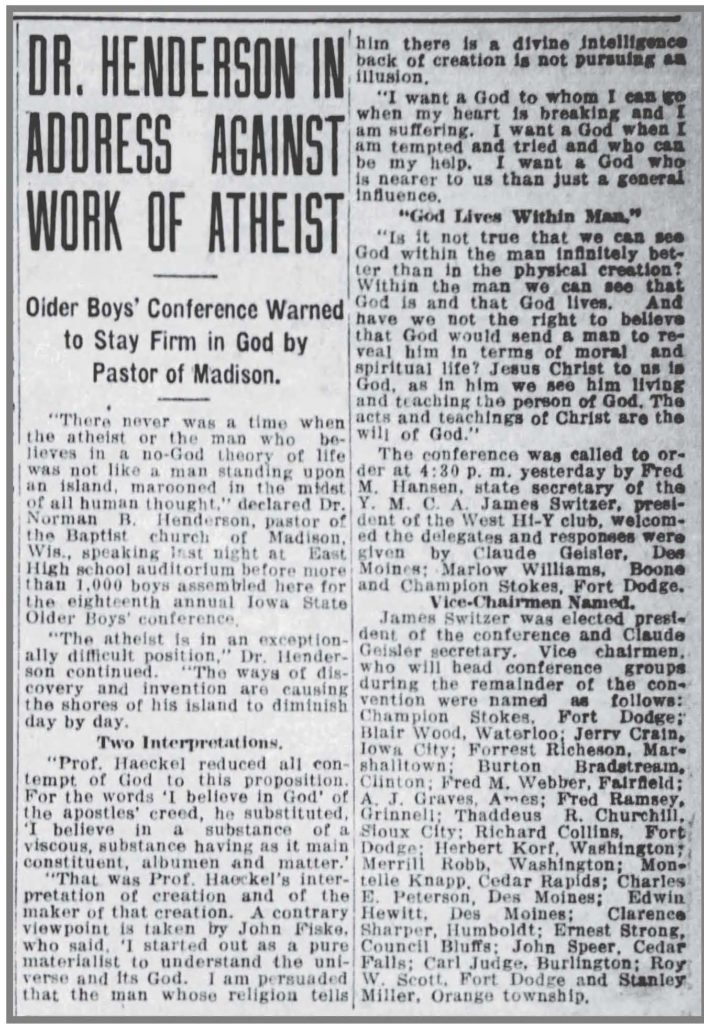

I found Fred Webber mentioned in this article from his Junior year about a Hi-Y conference. Fred was elected as one of the vice chairmen to lead conference groups during the conference.

Deacon: There are several references to Fred Webber as “Deacon” scattered throughout the yearbook. One is on his senior photo page at the top of this post.

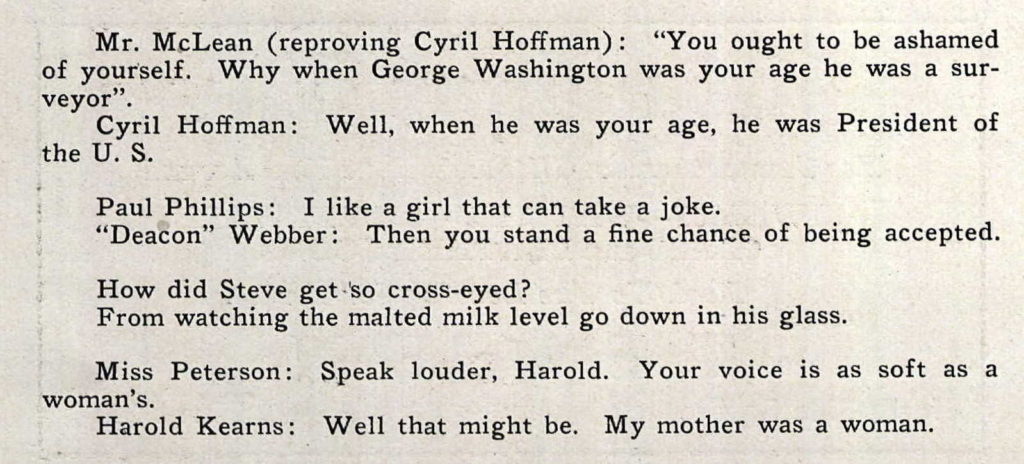

There are jokes and little stories among the advertisements at the back of the yearbook.

What would an old yearbook be without a class prophesy? Here is the part that pertains to great-uncle Fred:

What was it about Fred that earned him the nickname “Deacon?” Was it his participation in Hi-Y and all that “clean” living they were promoting? Did some of his speeches have a strong Christian bent? Was he a bit of a moralizer in his high school days? Was he always at church when he wasn’t debating or studying?

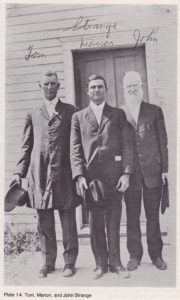

Fred grew up in a family of preachers. His father, M. D. Webber, was a Baptist preacher. His maternal grandfather, John Sylvester Strange, was a preacher. His uncle Thomas Madison Strange and his wife, Sarah Bird Strange were both preachers. His uncle Francis Marion Strange was a preacher. Maybe there were more, but those are the ones who come to mind. I don’t know how much time he spent with these aunts and uncles – they lived in other states, but the influence of faith and affiliation and a call to ministry was surely a part of the family culture and story.

Fred grew up in a family of preachers. His father, M. D. Webber, was a Baptist preacher. His maternal grandfather, John Sylvester Strange, was a preacher. His uncle Thomas Madison Strange and his wife, Sarah Bird Strange were both preachers. His uncle Francis Marion Strange was a preacher. Maybe there were more, but those are the ones who come to mind. I don’t know how much time he spent with these aunts and uncles – they lived in other states, but the influence of faith and affiliation and a call to ministry was surely a part of the family culture and story.

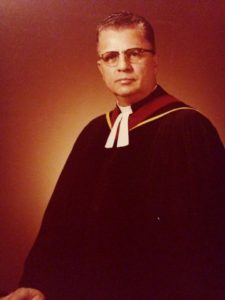

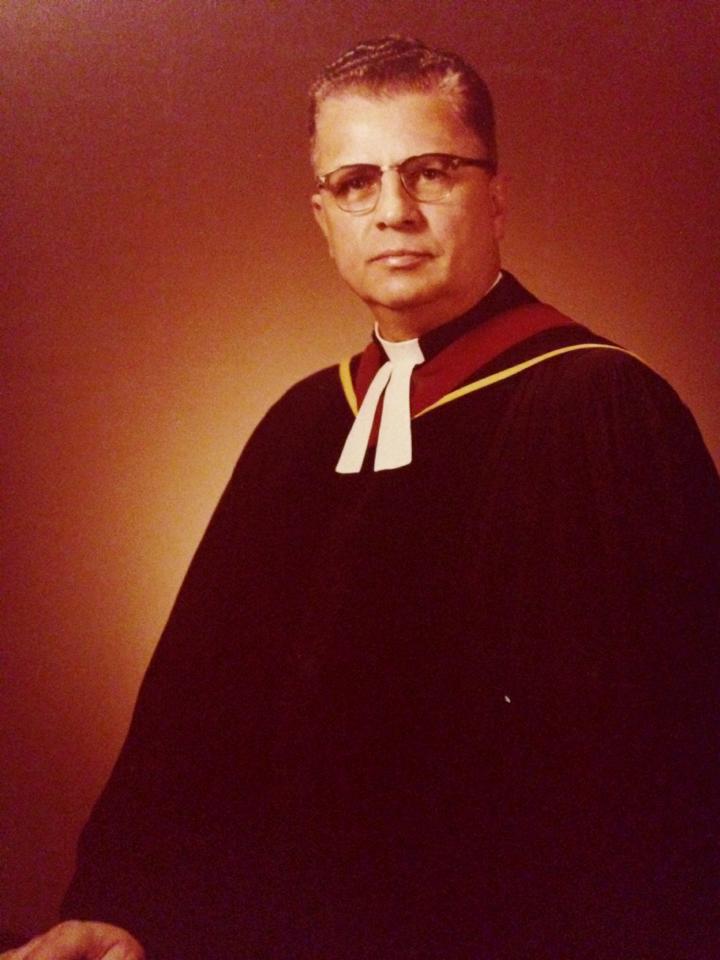

The nickname Deacon was more prophetic than the prophesy of Fred Webber running for a senatorship. Fred was ordained as a Baptist minister in April of 1932. He graduated with a degree of Master of Divinity from Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, a seminary with Baptist affiliation.

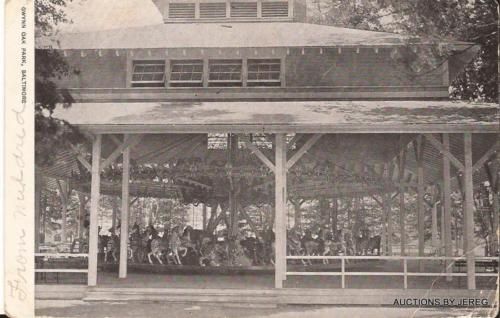

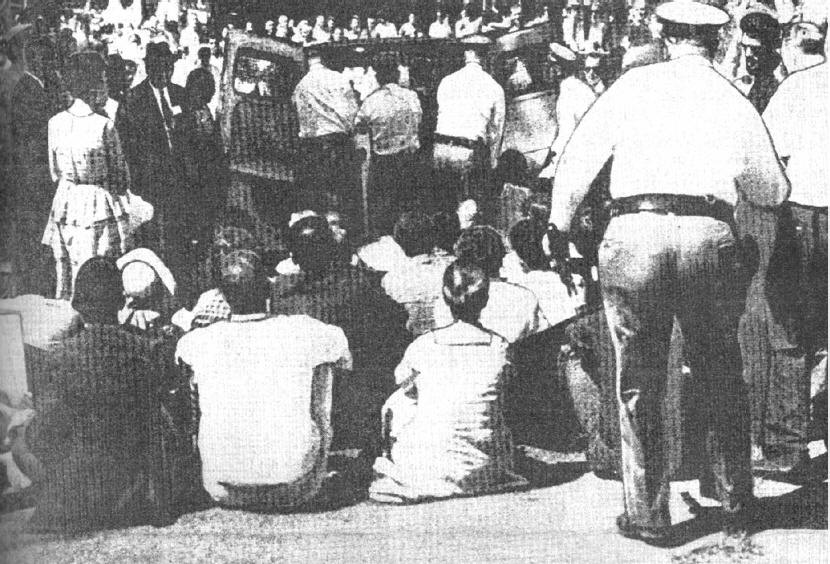

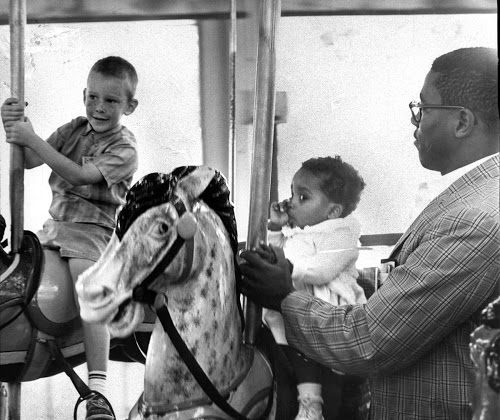

Fred later changed denominations, leaving the Baptists for the Presbyterians. After serving a number of churches, The Rev. Fred M. Webber was installed as General Presbyter of Baltimore on September 28, 1960.

I can’t help but wonder about the influence of S. E. Wallin, Fred’s debate coach on Fred. S. E. Wallin was a Presbyterian minister and missionary before becoming a teacher at Fairfield High School. Fred spent many hours under the tutelage of Rev. Wallin, both in debate and in Hi-Y. It makes me wonder if their relationship influenced not only his choice of career, but his later change of church affiliation. He certainly prepared “Deacon” Webber to think on his feet, to be well-prepared, and to seek understanding of both sides of the question at hand.

If you are interested in reading more about Fred M. Webber, he has his own landing page of posts I have written about him here.

Please take a moment to visit other Sepia Saturday participants here.