The month of January and a public health emergency declared in the northwestern U.S. because of a measles outbreak had me thinking about an uncle I never knew.

This is second in a series about my uncle, Wilbur Thomas Hoskins. You can read the first installment here: An Uncle I Never Knew – A Tow-Headed Boy.

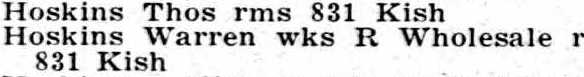

1929 brought the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. Times were hard for a coal miner who couldn’t count on steady work. My grandfather, Tom Hoskins, went to Rockford, Illinois, hoping to provide for his family. I don’t know if brothers Tom and Warren left for Rockford together, or if Tom followed his brother there. Both are listed in the 1929 Rockford City Directory, but only Warren was employed at the time of publication.

I tried to look up Kish street in Rockford, but it doesn’t exist. Kish seems to be short for Kishwaukee. Google street view shows their address as recently vacant/under construction, but this building, built in 1921, would have been across the street from them on the corner.

It was imperative that Tom find a way to provide for his growing family. In 1929 Wilbur was five; Albert was three; and by the end of the year, Eveline was expecting a third child, my mother.

It was imperative that Tom find a way to provide for his growing family. In 1929 Wilbur was five; Albert was three; and by the end of the year, Eveline was expecting a third child, my mother.

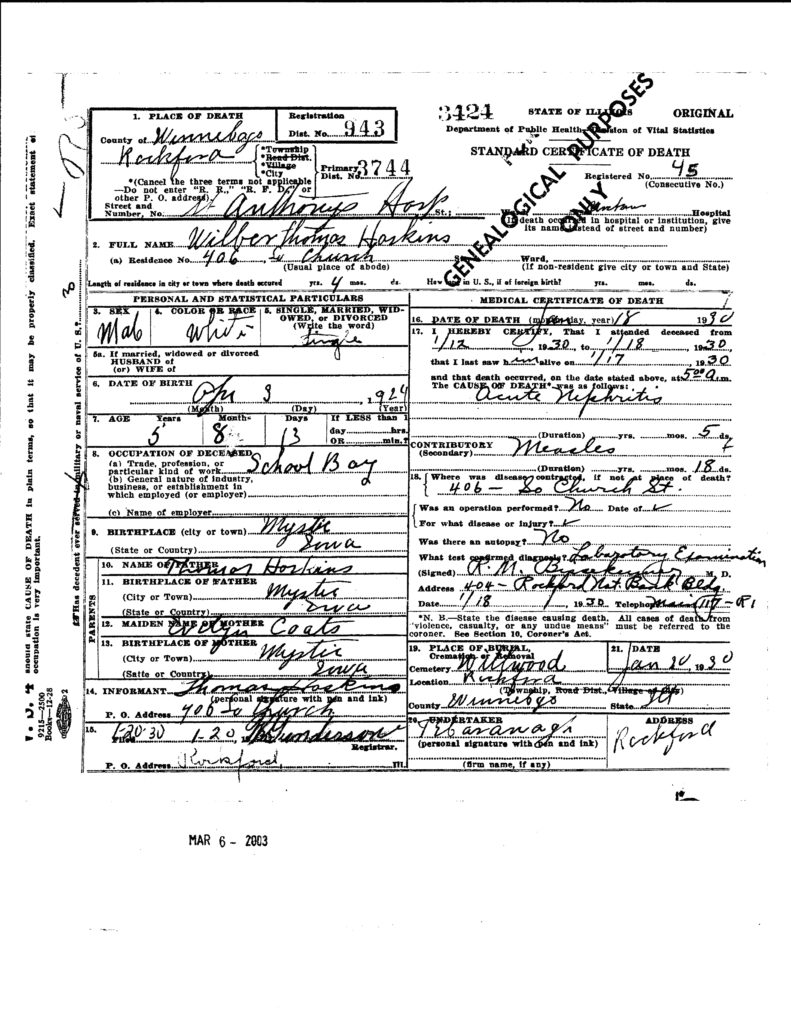

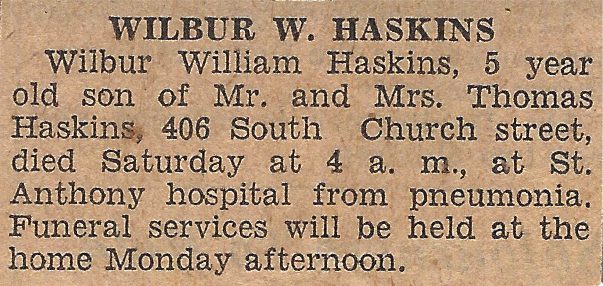

Eveline and Wilbur joined Tom in Rockford, but little Albert was left in the care of his maternal grandmother in their hometown of Mystic, Iowa. They were living at 406 S. Church Street in January of 1930 when Wilbur became ill. Among my grandmother’s papers were receipts for payments made for Wilbur’s medical care. They included Dr. Charles L. Leonard, Dr. R. M. Bissekumer, and St. Anthony’s Hospital.

The best efforts of his parents and the medical professionals were not enough to save Wilbur’s life. At 5:00 a.m. on January 18, 1930, Wilbur died at the age of 5 years, 9 months and 15 days while hospitalized at St. Anthony’s Hospital.

The cause of death recorded on Wilbur’s death certificate is “acute nephritis”, or inflammation of the kidneys. Contributory (secondary) cause of death – measles.

I interpret the death certificate this way: little Wilbur contracted the measles, developed inflammation of the kidneys as a complication, and this resulted in kidney failure. Inflammation of the kidney’s used to be called Bright’s Disease and this is what I had heard caused Wilbur’s death. There is a history of kidney problems among the male members of our family, so it is possible that Wilbur had an underlying condition.

One of the most common complications of measles, which often resulted in death, was pneumonia. The death notice in the newspaper (with a mix of facts and misinformation) cites pneumonia as the cause of death.

The death certificate shaved a month and two days off of Wilbur’s age. My grandmother, a former school teacher and stickler for details had her own accounting in the funeral record and hers are the numbers I used above.

People so easily forget how devastating a disease can be when it is no longer a part of our common experience. How else can we explain the growing number of people who do not vaccinate their children and the health emergency currently happening in northwestern states? This became personal for me when I had a stem cell transplant and lost all of my immunities. I had to repeat all of my vaccinations and be vaccinated for childhood diseases that I had as a child. I had to wait two years to receive vaccinations if they contained a live virus. When cases of measles made the news in my city while I was unprotected, I felt vulnerable. Vaccinations not only protect our own children, but people who are unprotected and have no control over it.

“Health officials in Washington have declared a state of emergency and are urging immunization as they scramble to contain a measles outbreak in two counties, while the number of cases of the potentially deadly virus continues to climb in a region with lower-than-normal vaccination rates.” (NPR)

“Before the widespread use of the vaccine, measles was so common that infection was felt to be “as inevitable as death and taxes.” In the United States, reported cases of measles fell from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands per year following introduction of the vaccine in 1963. Increasing uptake of the vaccine following outbreaks in 1971 and 1977 brought this down to thousands of cases per year in the 1980s. An outbreak of almost 30,000 cases in 1990 led to a renewed push for vaccination and the addition of a second vaccine to the recommended schedule. No more than than 220 cases were reported in any year from 1997 to 2013, and the disease was believed no longer endemic in the United States. In 2014, 667 cases were reported.” (Wikipedia)

Although this post has no images that reflect the theme image for this week, it is my contribution to Sepia Saturday. Please visit others who have responded to the prompt this week.

Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs. Historical photographs of any age or kind become the launchpad for explorations of family history, local history and social history in fact or fiction, poetry or prose, words or further images. If you want to play along, sign up to the link, try to visit as many of the other participants as possible, and have fun.