Sepia Saturday provides bloggers with an opportunity to share their history through the medium of photographs.

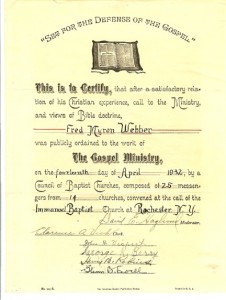

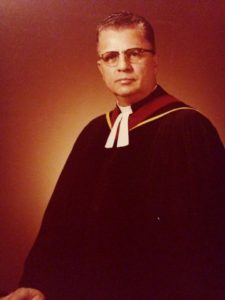

I started working on this post a couple of years ago. It wasn’t a Sepia Saturday submission at that time, but a continuation of my research into the life and times of my great uncle Fred M. Webber. The prompt image reminded me of this unfinished story. I’m afraid it will still be incomplete, but I’m going with it.

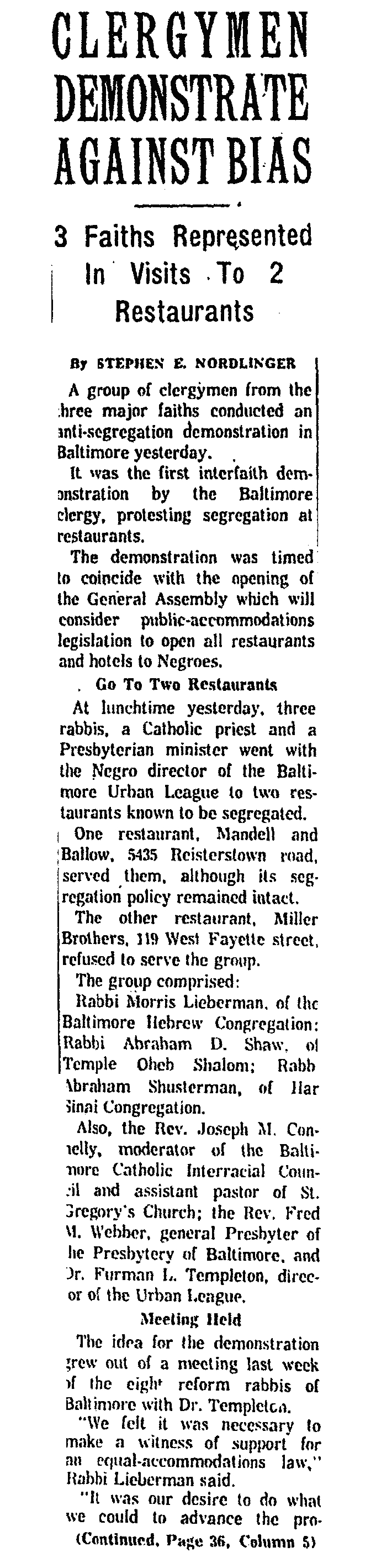

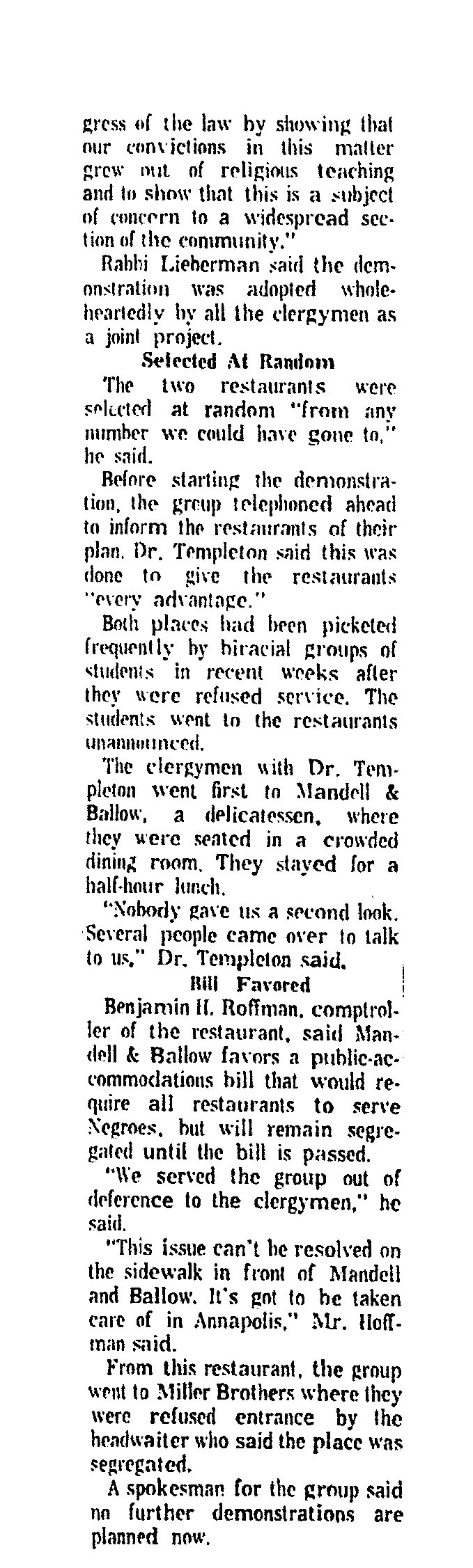

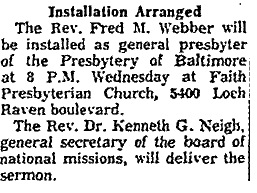

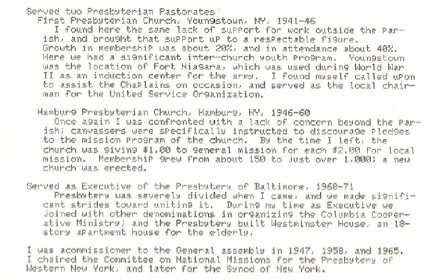

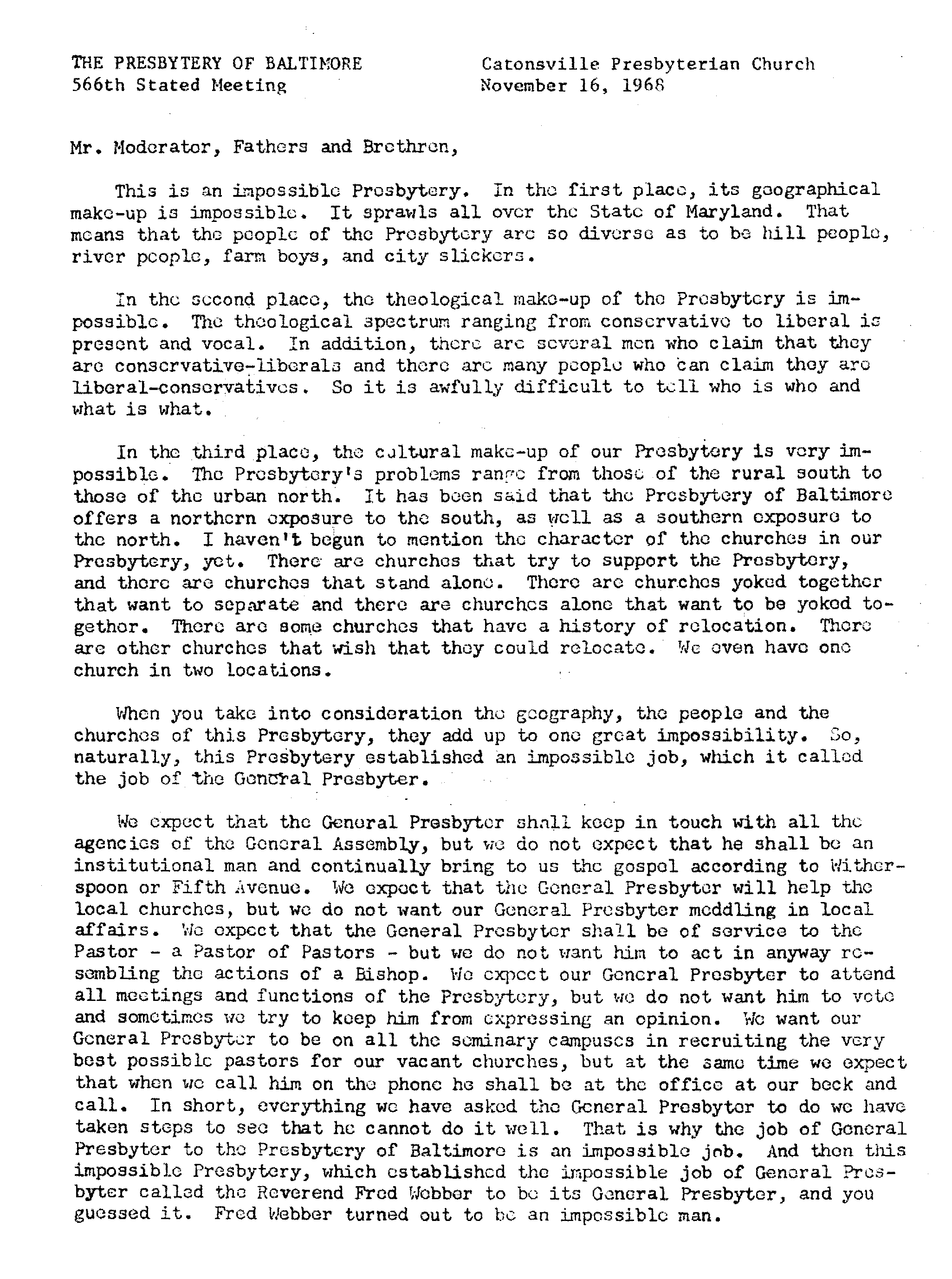

Reverend Fred M. Webber moved to the Baltimore, MD area in the spring of 1960 and was installed as General Presbyter of the Presbytery of Baltimore in September. He quickly became an active participant in an ecumenical group of clergy who were committed to advancing civil rights, fair housing, and other justice issues. In February of 1962, Fred and his clergy peers participated in a lunch counter demonstration at two segregated restaurants in Baltimore.

Reverend Fred M. Webber moved to the Baltimore, MD area in the spring of 1960 and was installed as General Presbyter of the Presbytery of Baltimore in September. He quickly became an active participant in an ecumenical group of clergy who were committed to advancing civil rights, fair housing, and other justice issues. In February of 1962, Fred and his clergy peers participated in a lunch counter demonstration at two segregated restaurants in Baltimore.

In a 1963 Christmas letter, Fred’s wife, Carol, reported that great uncle Fred had back surgery in June of that year, having two injured discs removed. Even so, Fred participated in the March on Washington in August. That’s a pretty fast turn around, in my opinion, since recuperating from back surgery can take some time and participating in such a large demonstration seems daunting. On the other hand, it was an opportunity to take part in an historic moment. Something not to be missed.

How did Fred M. Webber occupy himself during the time between his back surgery in June and the March on Washington in August? Carol says that Fred organized a committee during his recuperation that resulted in The Maryland Clergy Convocation on Religion and Race, featuring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the keynote speaker. I’m sure that was a highlight of the year!

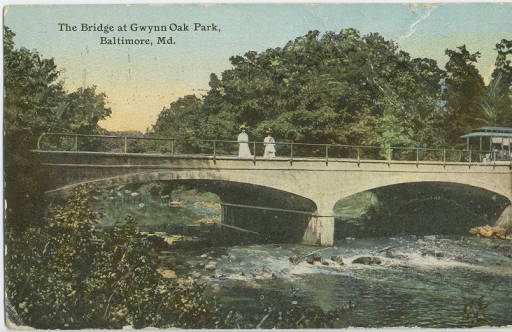

Following the tradition of using the celebration of freedom and national pride to put a spotlight on injustice, civil rights activists in Baltimore, MD staged a demonstration at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park on July 4, 1963. I think we can safely assume that Fred was recuperating over the 4th of July holiday and missed out on the action. Fred’s daughter, who was a senior in high school at the time and didn’t always pay attention to the details of her parents’ lives and conversations, does remember overhearing the park being a topic of conversation and that discrimination was at issue.

Following the tradition of using the celebration of freedom and national pride to put a spotlight on injustice, civil rights activists in Baltimore, MD staged a demonstration at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park on July 4, 1963. I think we can safely assume that Fred was recuperating over the 4th of July holiday and missed out on the action. Fred’s daughter, who was a senior in high school at the time and didn’t always pay attention to the details of her parents’ lives and conversations, does remember overhearing the park being a topic of conversation and that discrimination was at issue.

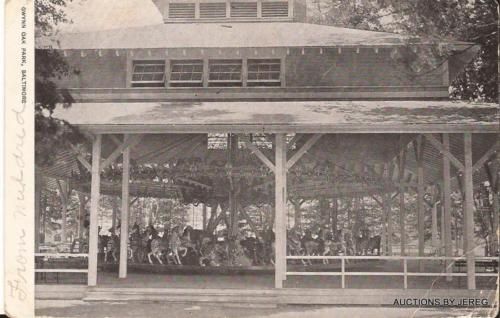

Gwynn Oak Park opened in 1894 as a Trolley Park, a picnic and recreation area built by a trolley company whose streetcar line ran past the park. Trolley parks were precursors to amusement parks and the companies who built them hoped to encourage ridership, especially on weekends. In the photo below, you can see a streetcar on the far right.

And a later photo of a street car with a Gwynn Oak roller coaster in the background.

Most trolley parks did not charge admission, but did charge for rides. Gwynn Oak had a Ferris Wheel, two wooden roller coasters, bumper cars, The Whip, and a merry-go-round.

Gwynn Oak Park was whites-only from the beginning. Segregation by rules and laws was the norm across the South.

“By the end of 1955, Baltimore’s Jim Crow system had a few dents in it. The city had survived its first year with desegregated schools. College students had managed to end discrimination at all of the city’s Read’s drug stores. Lunch counters at many low-cost variety stores had also been integrated. However, big, expensive, downtown department stores still had Jim Crow rules. So did most of the city’s restaurants, movie theaters, and hotels.” (Nathan, 2011, p. 62.)

By 1954, local civil rights activists turned their attention to Gwynn Oak Park. They first tried persuasion, picketing, and handing out fliers. Small groups of blacks and whites entered the park and attempted to buy tickets, only to be turned away. The activists decided to target the park’s annual All Nations Day Festival, the park’s biggest money-maker. The festival was also chosen because it was not “all nations” as promoted. Embassies of African countries were not invited – and local citizens of African ancestry were not admitted. On Labor Day 1962, the Baltimore chapter of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) picketed All Nations Day for the ninth year in a row. By this time, the group had become more media-savvy and also decided to approach the invited embassies and discuss the discriminatory practice. The Indian Embassy said they would not participate if there was discrimination; it made the news; and all of the other invited embassies followed suit.

Even with the bad publicity, Gwynn Oak remained a whites-only park. More bad press followed when the superintendent of Baltimore’s Catholic schools announced that parochial schools would no longer hold picnics at Gwynn Oak.

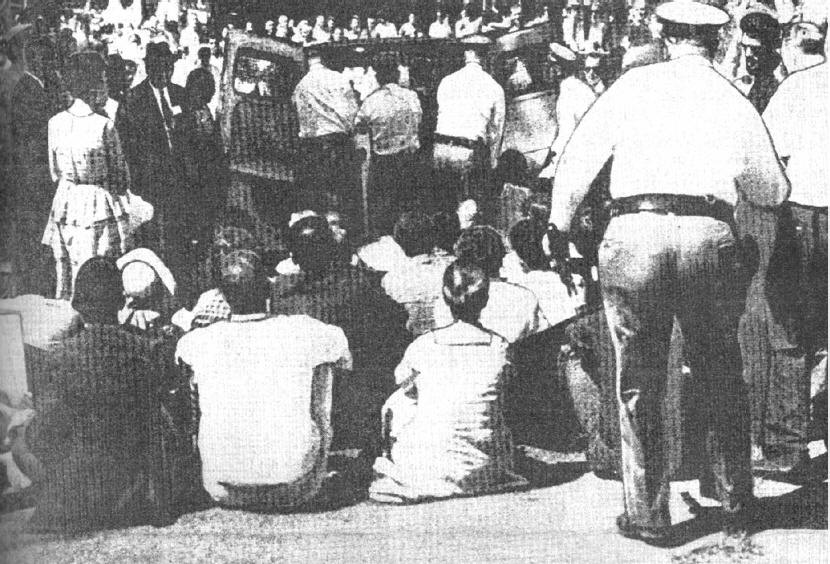

The events that finally resulted in the park being desegregated occurred on July 4 and July 7 of 1963. The July 4th demonstration included protesters from out of state as well as prominent religious leaders. The press knew what was about to happen. The police were made aware of the size of the planned protest and worked with the organizers. The organizing groups involved wanted great impact, but no violence.

Dr. Eugene Carson Blake, a white Presbyterian minister spoke at the pre-demonstration rally on Thursday morning, July 4th. Dr. Blake came from New York to attend the demonstration and, as the national head of the United Presbyterian Church, he was the most famous of the out-of-town participants and was responsible for many of the clergy being there.

When the protestors arrived at the park in the early afternoon, about 1500 white customers were inside, enjoying the park on a hot summer day. Some of the protestors formed a picket line in front of the park entrance while others formed groups and prepared to enter. The first group to walk up to the ticket booth included the most newsworthy demonstrators: Dr. Blake (Presbyterian), Bishop Daniel Corrigan (Episcopal), Rev. Bascom (local activist and minister), Ed Chance (CORE), Furman Templeton (Urban League), Father Joseph Connolly (Catholic). The photo below includes Dr. William Sloan Coffin (Methodist) in front.

For three hours, group after group approached the ticket booth and then walked out under arrest, accompanied by police officers, to board police vans and busses. Some protestors sat and refused to move and had to be carried out by police.

You can watch the arrest of Dr. Blake (in the white hat) and listen to his words in the video below.

Although the ministers, priests, and rabbis got the bulk of media attention, most of the demonstrators were young people. By the end of the day, 283 protestors had been arrested, including more than twenty religious leaders. These numbers overwhelmed the Baltimore police and judicial systems.

… When a reporter asked Rabbi Lieberman why he had joined other clergy to be arrested, he smiled and said, ‘I think every American should celebrate the Fourth of July.'” (Nathan, 2011, p.160.)

As big and impressive as the July 4th protest was, it did not end the whites-only policy. The leaders organized a committee while they were in jail to plan more demonstrations and immediately went into action. Another protest followed just three days later, on July 7th. This protest did not have the numbers of prominent and out-of-town participants, but several of the local clergy encouraged members of their congregations to join them. This time the 300 civil rights protestors were outnumbered by more than 1500 segregationists – a group more hostile and willing to throw rocks than the crowd on July 4th.

Ninety-five civil rights protestors were arrested that Sunday, including thirteen local clergymen, one of whom dressed up in a red-white-and-blue Uncle Sam costume to show that he felt protesting was patriotic. (Nathan, 2011, p.179.)

There is so much more to the story than I have included here and I need to wrap things up! I didn’t even mention the owners of the park … If you have an interest, most of my information came from the book Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement, by Amy Nathan. And there is quite a bit of information online.

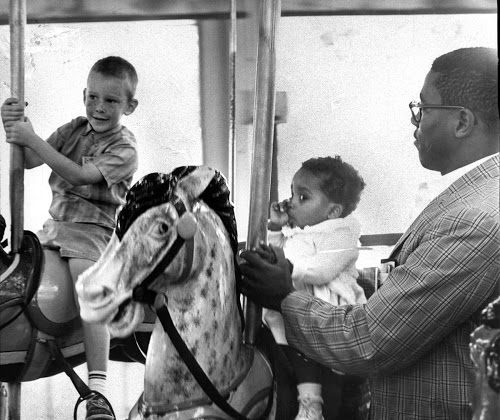

Threats of further protests, talks, and negotiations finally resulted in Gwynn Oak Park opening its doors to the black community on August 28, 1963 – the same day as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. And we know where Fred M. Webber was on that day!

Sharon Langley became the first black child to go on a ride in Gwynn Oak – the merry-go-round.

“Two white youngsters about age six – a boy and a girl – climbed onto horses on either side of Sharon. They were big enough to ride by themselves, but the girl’s mother asked Mr. Langley to keep an eye on her daughter to make sure the little girl would be safe during the ride. He was glad to help. This perfectly normal parent-to-parent request – so typical of the way parents help each other at playgrounds and parks – took on special meaning this day. ‘These are the kinds of things that make me feel we’ll be accepted,’ he told a reporter later.'” (Nathan, 2011, p. 204.)

Some of the names in this story (some included in this post, some not) have direct links to Fred M. Webber, including Father Joseph Connolly and Furman Templeton. And, I’m guessing that Dr. Eugene Carson Blake was in some sense Fred’s boss. It makes sense to me that Uncle Fred was involved in some way with activities and/or planning that happened before and during the protests at Gwynn Oak Park since he met frequently and served in various roles with those who were there that day. I would also venture a guess that he was disappointed that he could not be there.

John Waters, who wrote the movie Hairspray is from Baltimore. He made up most of the events in the movie, but Tilted Acres, the amusement park in the movie, is based on Gwynn Oak Park and there really was a dance show similar to the one in the movie. The real Buddy Deane Show was whites-only, except one day a month when it was blacks-only. In 1962, there was a protest against the segregated show, and an integrated “dance-in” took place August 12, 1963 – just days before the integration of Gwynn Oak. The show was cancelled in 1964.

Well, that’s my take on the theme image today. Hop on a trolley or a roller coaster if you prefer, and see how others have interpreted the theme image at Sepia Saturday.

Nathan, A. (2011). Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement. Philadelphia: Paul Dry Books.

P.S. If you are interested in reading more about my great-uncle Fred, take a look at the Fred Myron Webber page.