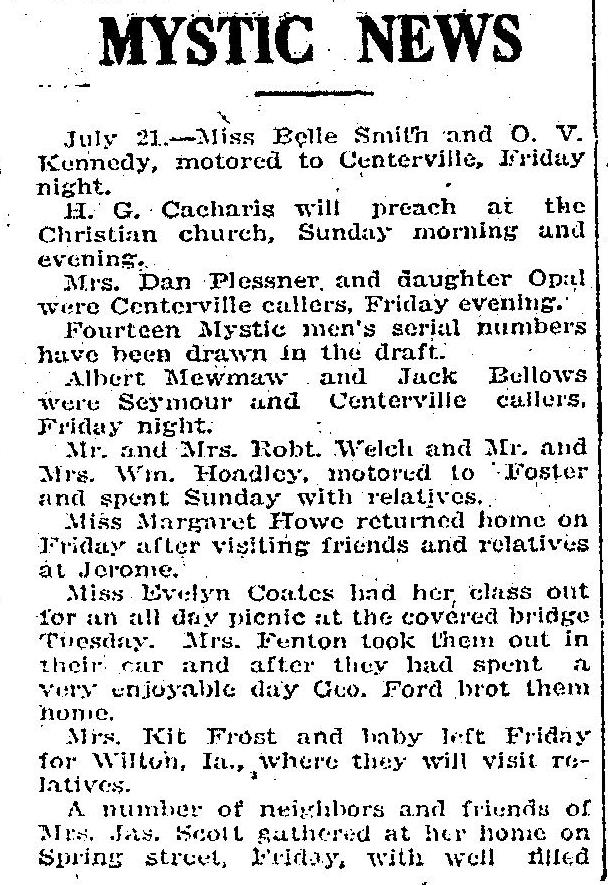

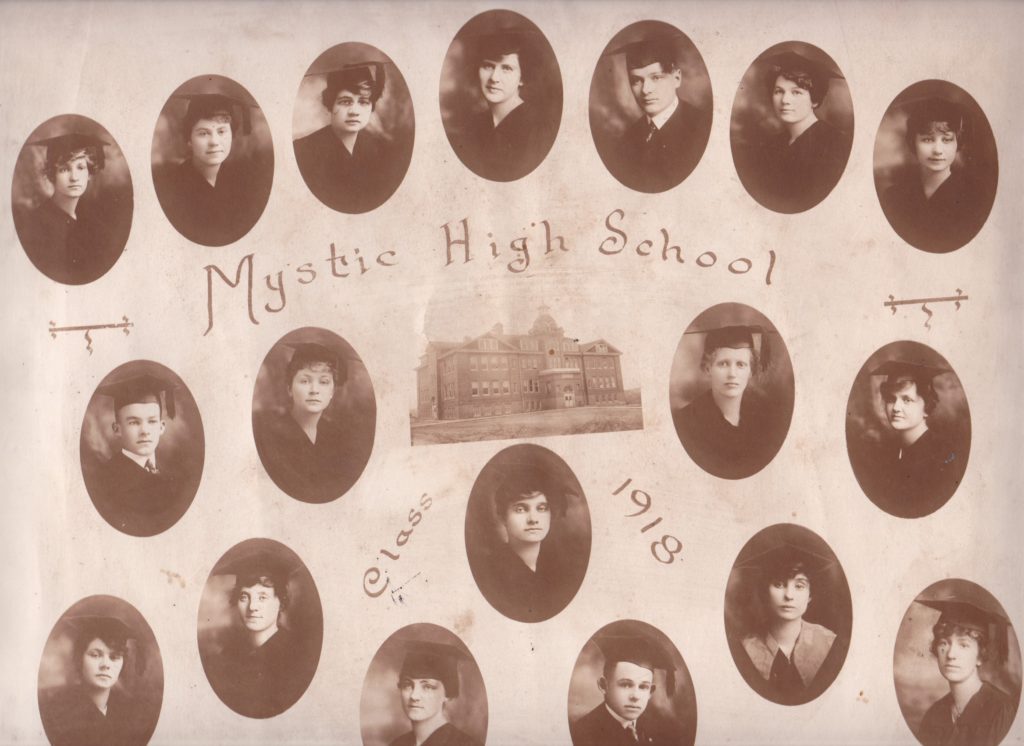

I shared a photo of my grandmother Eveline Coates’ high school graduating class in Mystic, Iowa a few weeks (now months!) ago. Along with the photo and her diploma, a couple of other mementos were saved. One is the program for the Junior-Senior Banquet in honor of the graduating Seniors. It was interesting to see how World War I seemed to be the overarching theme of the festivities. I decided to take a deeper look at what her life may have been like during the 1917-1918 school year. There was a lot going on, a war and the beginning of an influenza pandemic to name the two biggies. The list of related posts is getting long, so I’ll link them at the bottom.

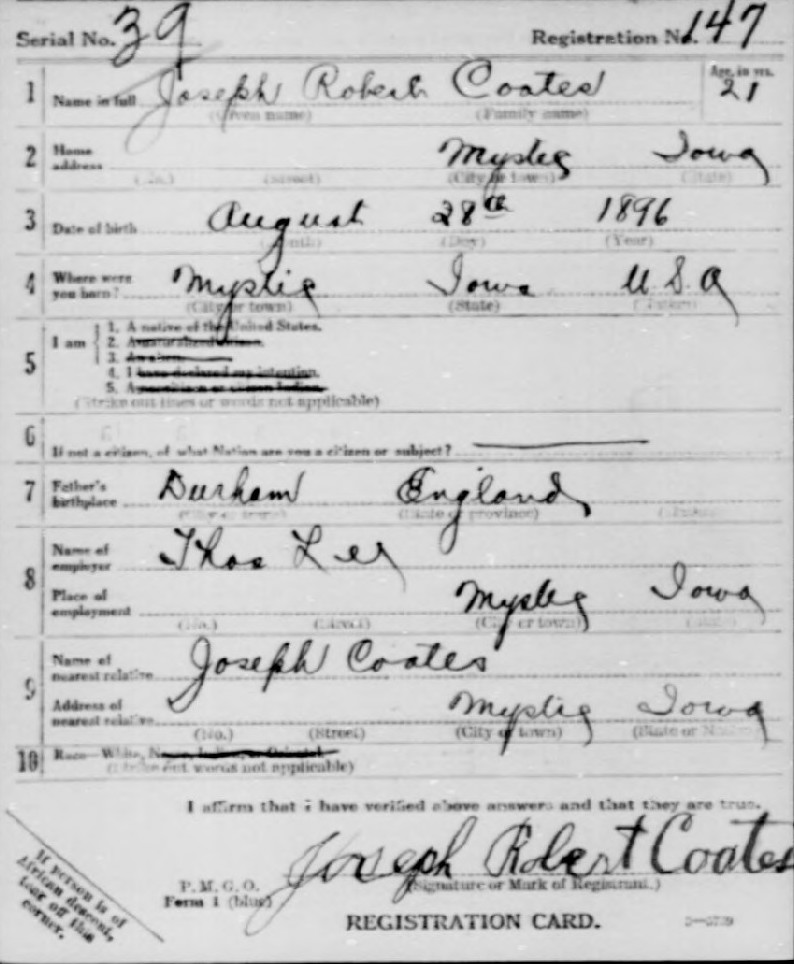

When I wrote my last post, I completely forgot about Eveline’s brother Joe! When Joe registered for the draft in 1917, he reported that he worked for Thomas Lee – not the same employer as his brothers.

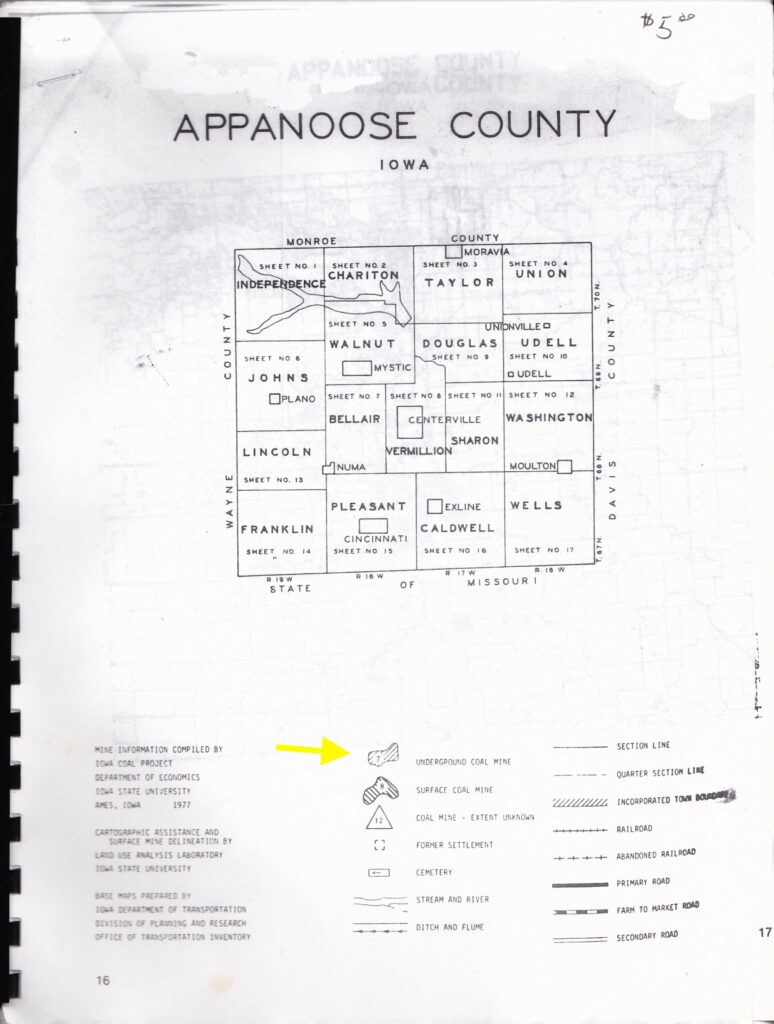

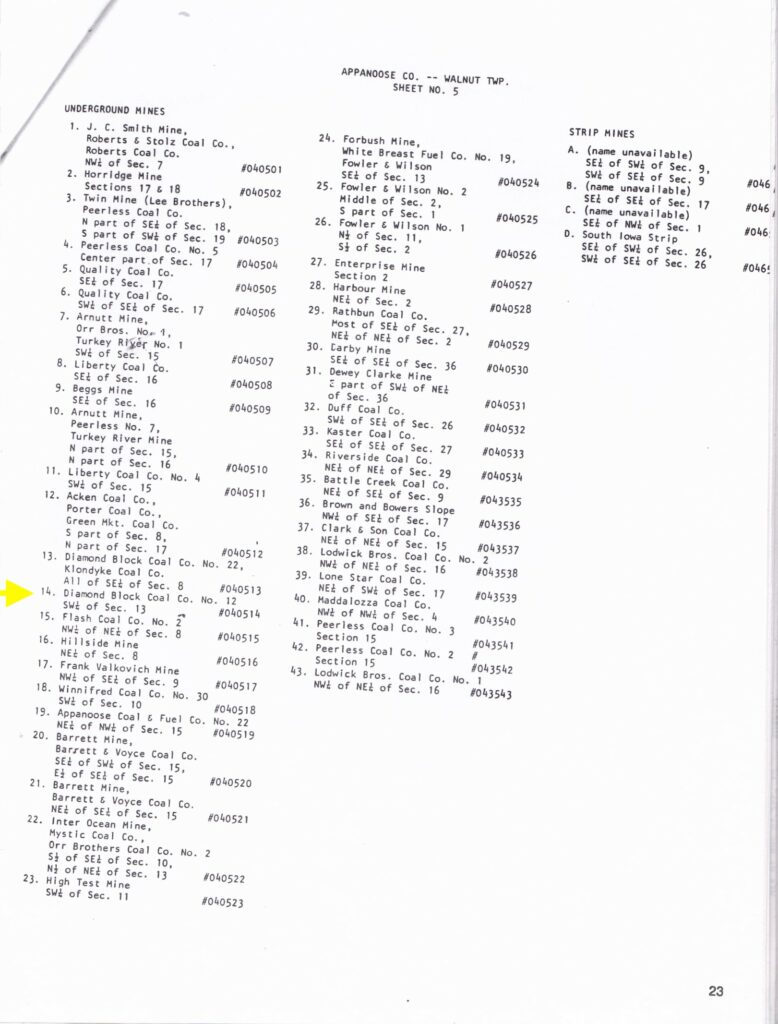

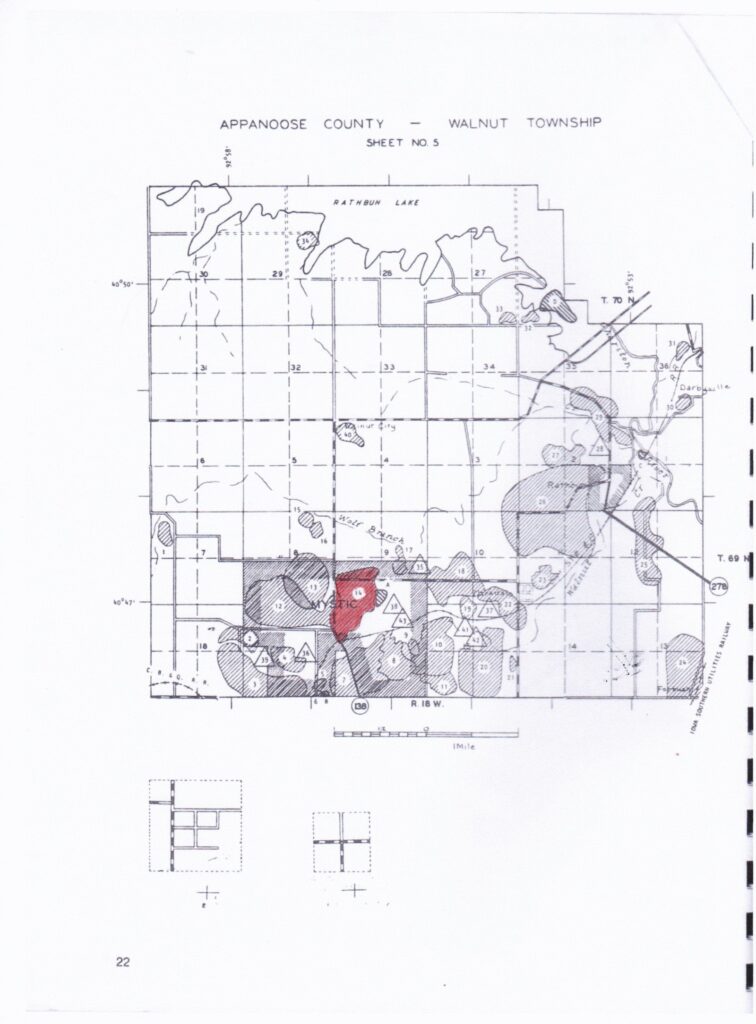

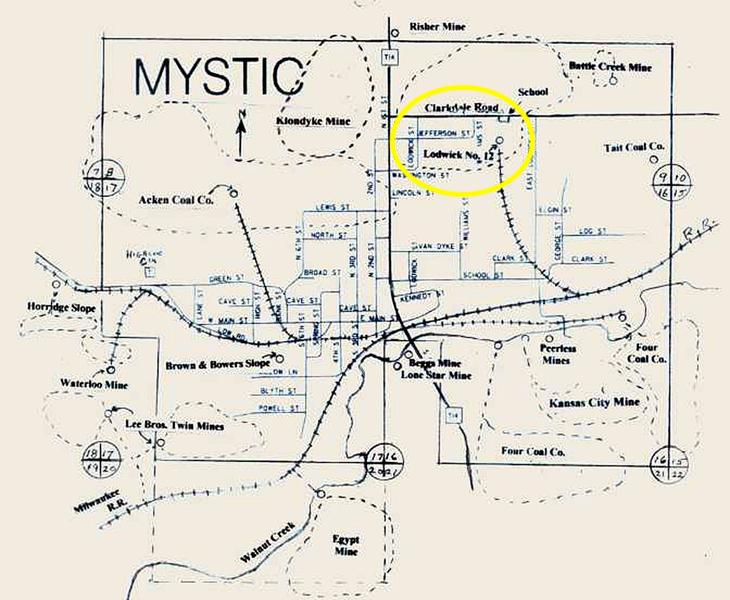

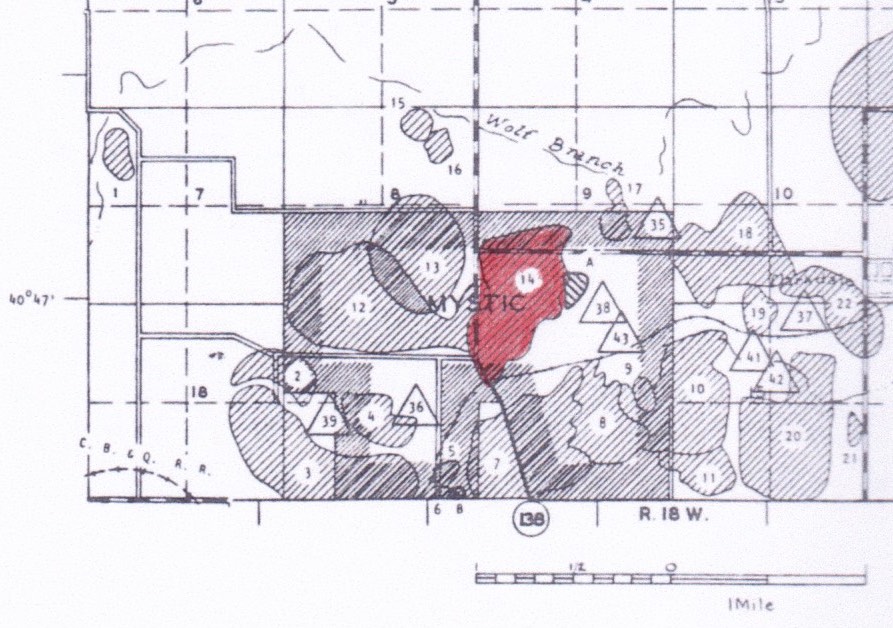

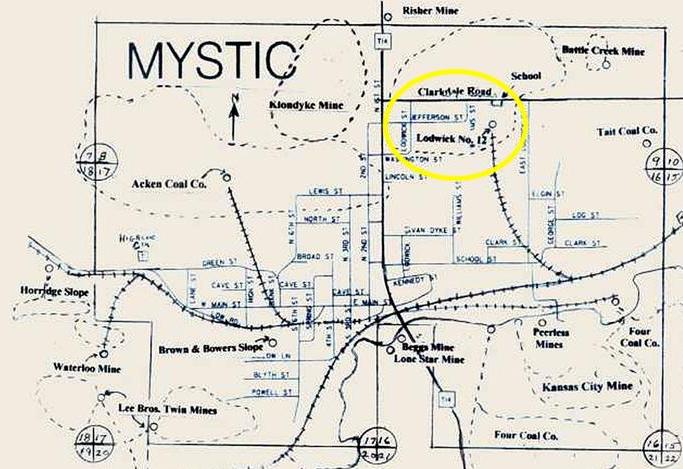

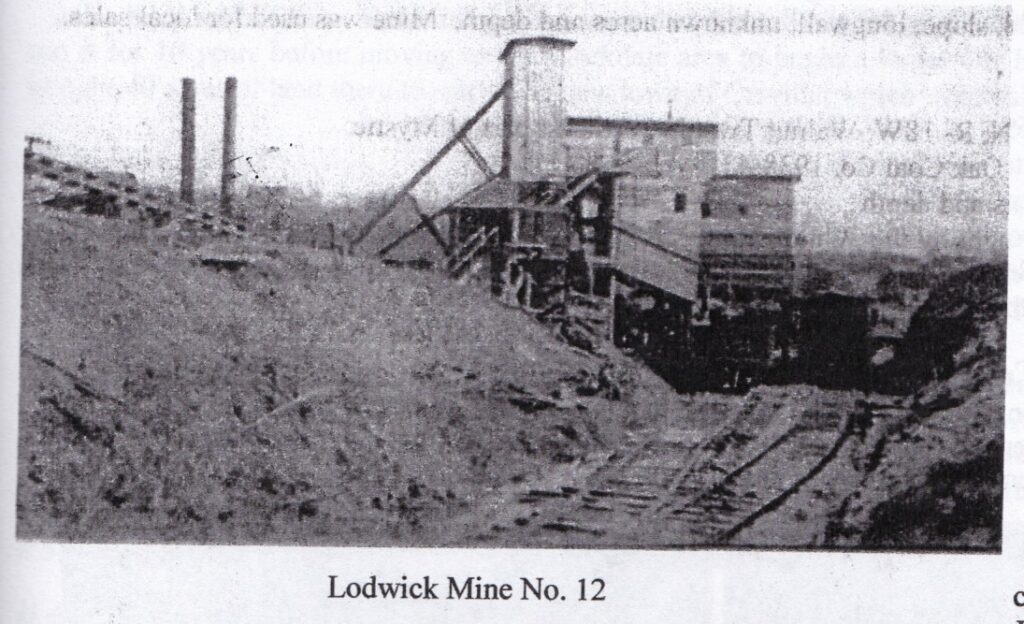

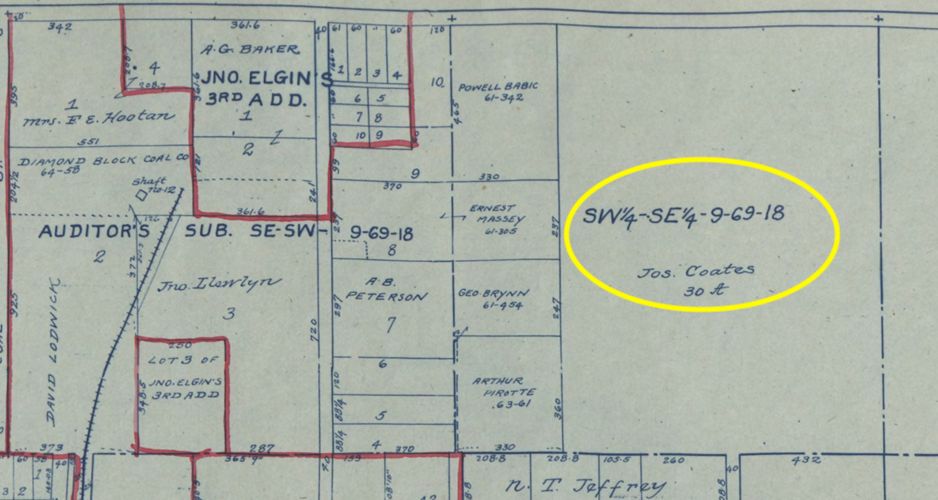

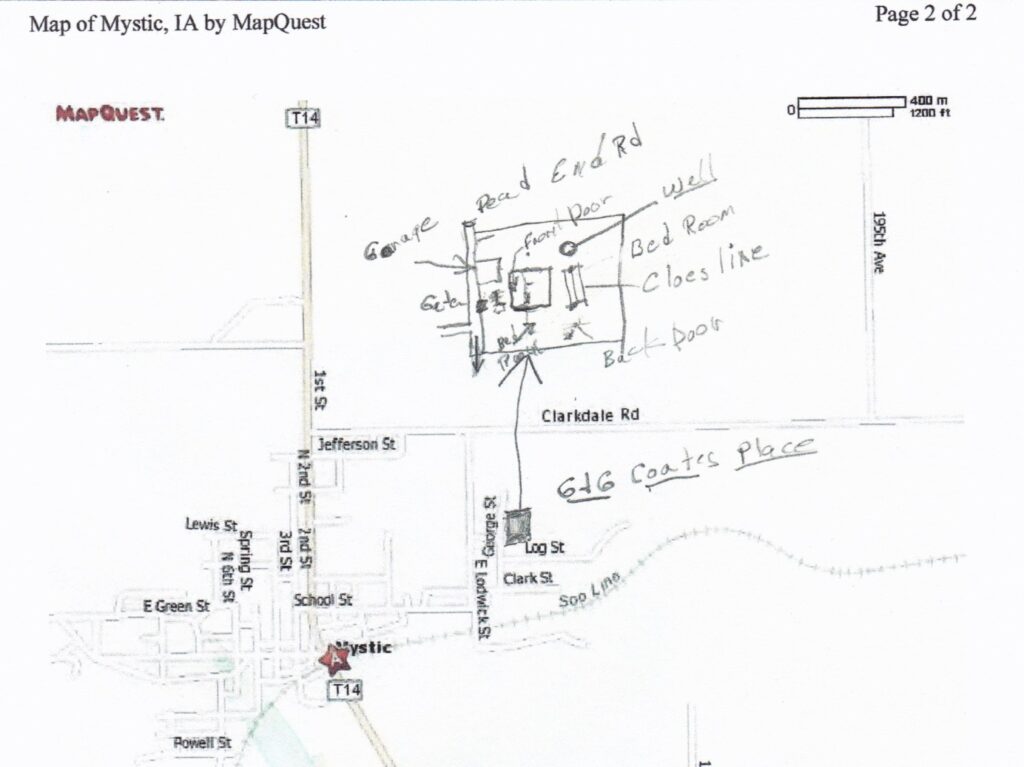

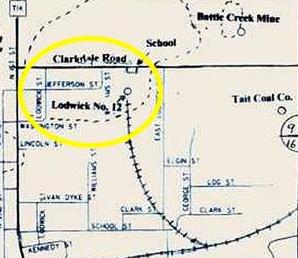

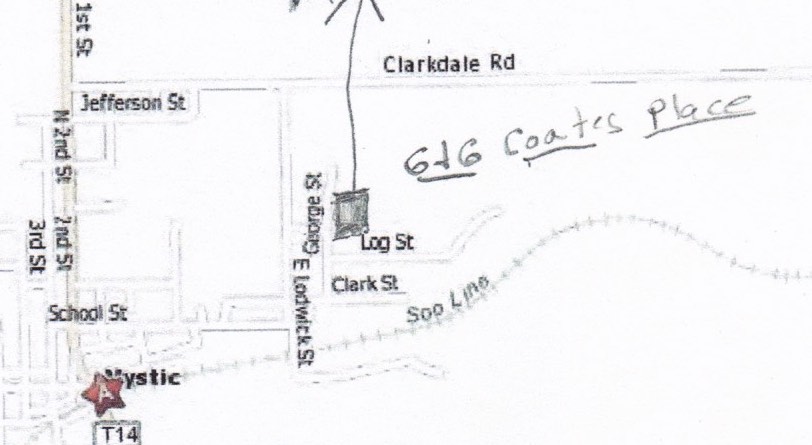

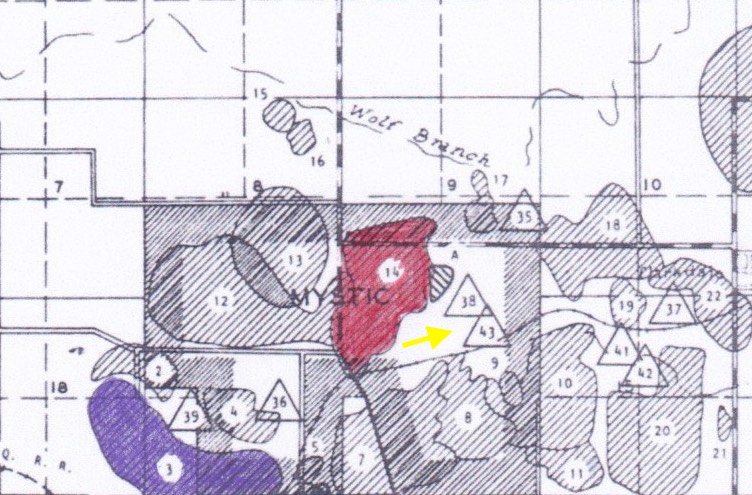

Thomas Lee was one of three brothers who owned the Lee Brothers Coal Company. Thomas managed the Twin Mines, where he employed 300 men in 1916. Twin Mines had two 40-feet shafts, one on either side of the railroad tracks that led to long tunnels to two mines. I updated the map I shared last time to indicate the two mines where Eveline’s brothers, and probably her father, worked. The Coates family lived southeast of the #12 mine, less that 0.3 of a mile away.

Purple = Twin Mines

Arrow is an approximate of location of the Coates’ home

During the days while the mines were operating in full swing, the lives of the miners’ families were practically ruled by the mine whistle. At 6 a.m. the whistle signaled the miners should be up and getting ready for the days’ work. The 7 a.m. whistle meant it was time for the day’s work to begin. The noon whistle signaled lunchtime for both the miners and the school children. The 3 p.m. whistle signaled that the miner would soon be home and that it was time for his wife to start the evening meal. One long blast at 4 p.m. meant that there would be work tomorrow, and three blasts meant no work.

HEUSINKVELD, W. M. 2007, THE HISTORY OF COAL MINING IN APPANOOSE COUNTY, IOWA, P. 20.

One can imagine the Coates home – and most of the community – rousing with the 6:00 whistle. Although I suspect many of the wives and mothers were up earlier, preparing a hearty breakfast and hot coffee for their miners and packing lunches for them too. For Eveline’s mother, that meant breakfast, coffee, and lunches for the four miners in the family plus feeding Eveline and her five younger siblings and getting them off to school. With no electricity, no running water, and a coal stove. As the oldest daughter, Eveline may have had some morning duties before leaving for school, perhaps helping the younger children. Joe had a longer walk to work, so he likely left home earlier than the others. As a side note – when Eveline married, her husband (my grandfather) also worked in the coal mines. Even long after retirement in another city, she seemed to keep that early schedule. Up very early (I never ate breakfast with them when I lived in their home), the evening meal around 4:30, and off to bed at 8:00.

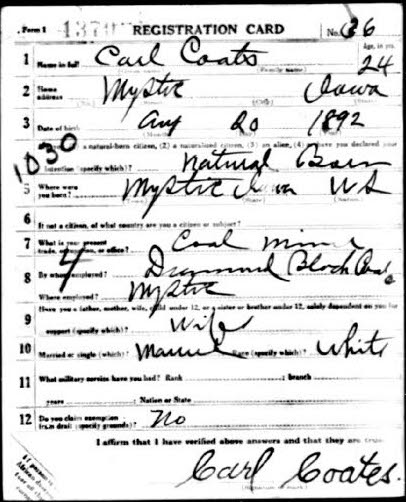

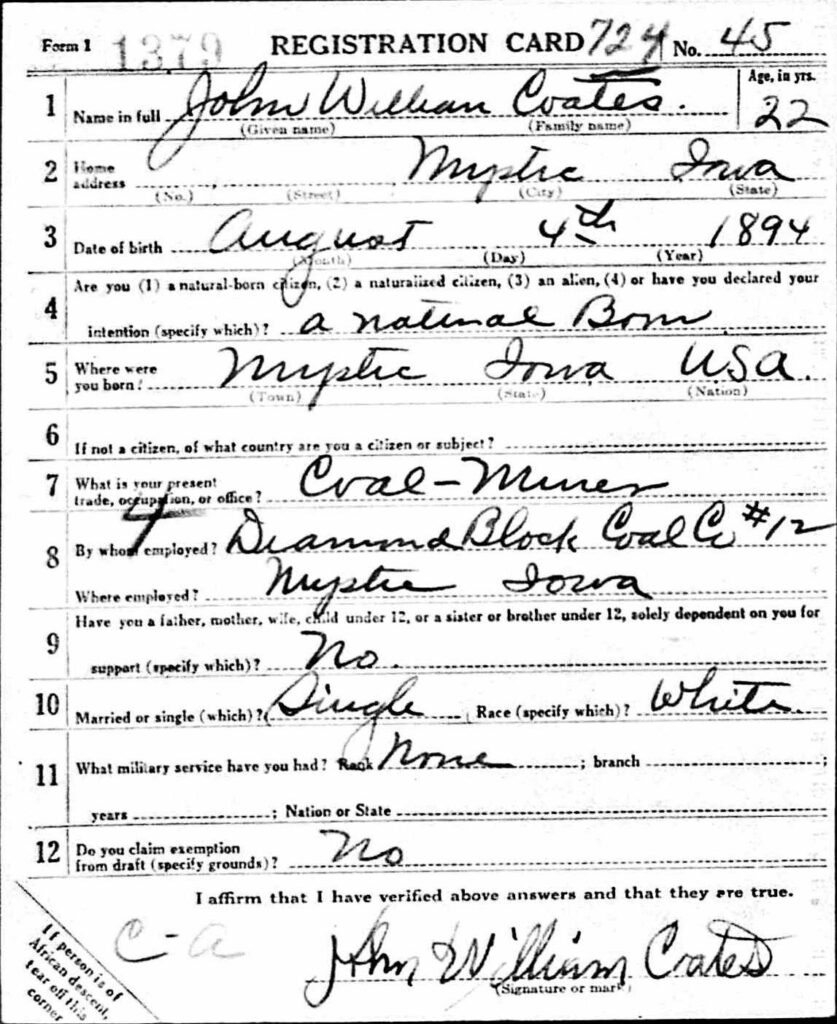

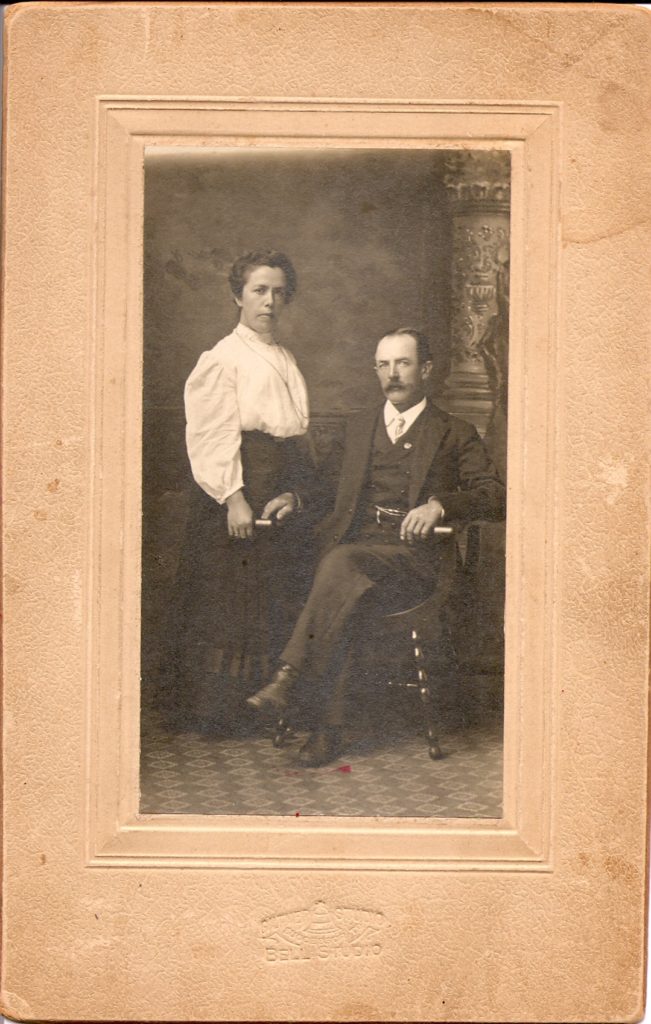

Eveline’s father, Joseph Coates, is sometimes listed in the census and other records as a miner and sometimes as a carpenter. I was always told that he was a carpenter in the mines, although I now know that there were years that he was shoveling or picking coal. After some time working at both mining and carpentry, maybe he was hired to do carpentry work in the mine. His own father was a joiner (carpenter) in a coal mine in Durham, England. In the 1910 federal census, Eveline’s brother Carl is listed as a mule driver in a mine. In other years, he is listed as a miner.

When the whistle wailed day or night, it was a frightening sound because it was a danger signal. It might be a warning of a fire so that everyone would grab a bucket and rush to the scene. At night the wailing sound might warn of an approaching storm so that people could seek the safety of their storm caves. However the sound that was seldom heard, but could send shivers up one’s spine was the six long, sad wails that told that a miner was dead. All the women came out to find out if their loved one was a victim of one of the many underground dangers.

HEUSINKVELD, W. M. 2007, THE HISTORY OF COAL MINING IN APPANOOSE COUNTY, IOWA, P. 20.

The quote above implies that the whistle signaled a death only when the death occurred in the mine. Many injuries would have been minor and not requiring a stretcher lowered into the shaft to bring up the injured miner, but that was obviously not always the case. Living in a small mining community, everyone surely knew everything that happened in the mines – and not just the mines in Mystic. The miners had a union and the newspaper reported injuries and deaths throughout the county. My limited research found some serious injuries and some deaths in Mystic during Eveline’s senior year of high school. Fortunately none in her family.

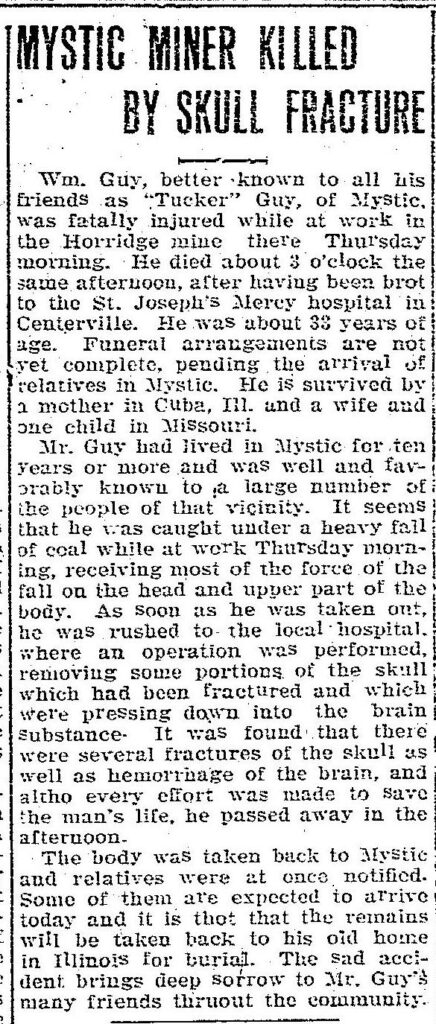

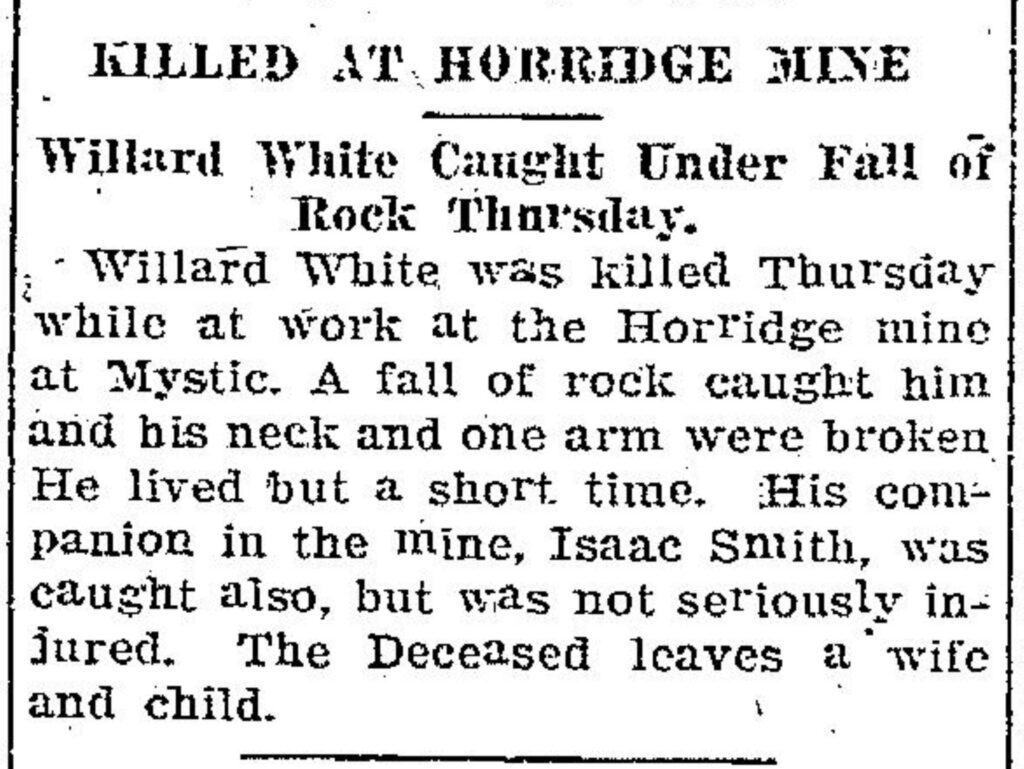

In June of 1917, a Mystic man died of injuries sustained at the Horridge Mine. Did the whistle wail six times? Probably not, as he was alive when he was pulled out of the mine and died in the hospital three hours later.

Charles Mickey, also of Mystic, was injured at the Porter mine in January of 1918. He died in April.

Another death at the Horridge Mine, this time in April 1918.

15 April 1918

There were also reports in the news of more minor injuries and a couple of lawsuits brought by miners for injuries sustained at work.

Not only was coal mining a dangerous job – there were other difficulties. Wages were low; there was not always work, especially during the summer; there were layoffs and strikes. The war also impacted the work and wages of the miners. I’m not going to attempt to delve into any of that.

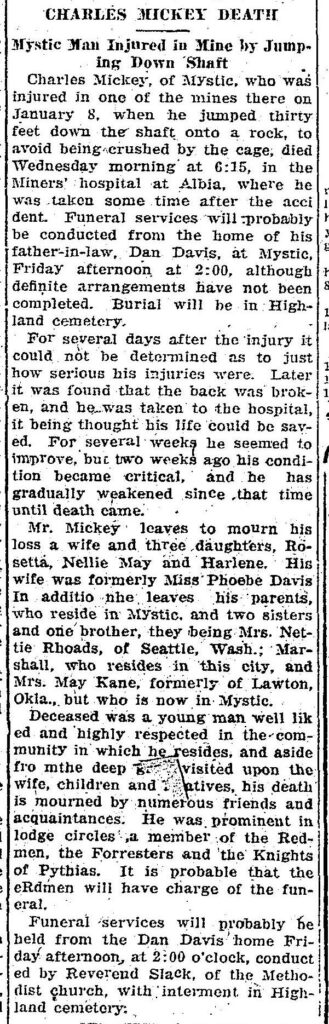

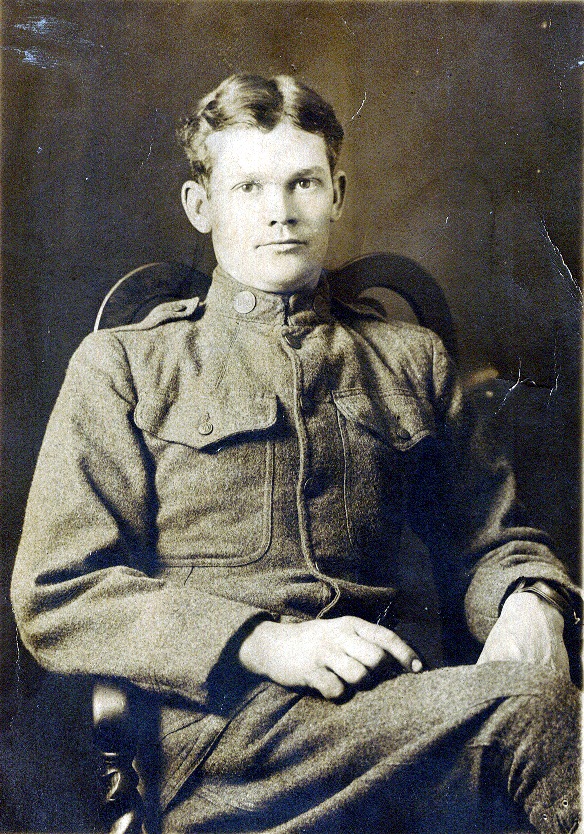

Below is an undated photo of my grandfather, Thomas Hoskins (Eveline’s future husband), and Miles Bankson (her sister Blanche’s future husband), sitting atop some structure along a track at one of the coal mines. They are not dressed for work – looks like their Sunday best.

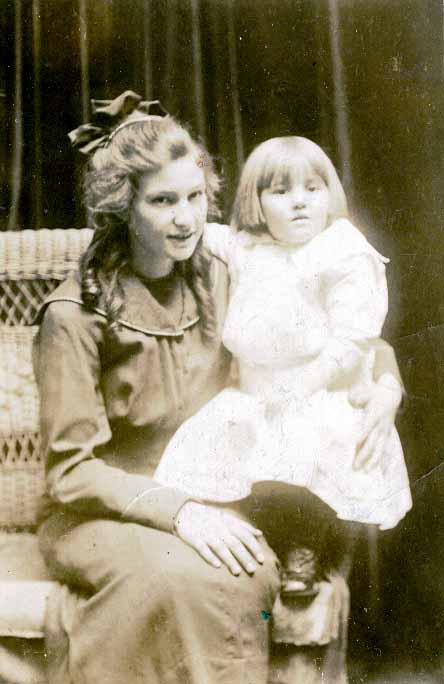

Another mining related family photo – Eveline’s sister Blanche, who married Miles Bankson. Were they on a date?

The video below offers a glimpse into mining in Appanoose County. The New Gladstone Mine was in operation until March 1971, when it closed for highway reconstruction. The Gladstone Mine was the last pony mine operating in the United States. Shetland ponies were used to haul coal from deep shafts to the surface. Before the mine was completely closed and sealed, Iowa State University in Ames made a 23-minute documentary of the mine. Mine workers re-opened the mine and started the machinery long enough to make the film. One of the miners said that he began working in the mine in 1916. He is the man with an accent that differs from a typical Iowa accent – and is a reminder of the many immigrant families who migrated to Appanoose County to work in the mines. There is electricity in the mine in this film – lightbulbs strung throughout, which was not the case in 1918. There may be a few other improvements that occurred over the years, but it looks like it must have operated very much like it did when it first opened, even into 1971.

Miners were paid by the weight of coal they produced each day. Everyone bore the weight of potential injury or death of themselves or loved ones. Often that injury was caused by the weight of a large piece of coal falling. Coal mining families bore the weight of little, or no, income. Needless to say, coal mining was work that could “weigh” on a person.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday, where the prompt photo suggests we consider weight.

Please visit other Sepia Saturday participants here: Sepia Saturday. And if you would like to read other posts about Eveline’s Senior Year, you can find them here:

Eveline’s Senior Year, Part 1

Eveline’s Senior Year: The Draft and a Carnival

Eveline’s Senior Year: A Look Around Town

Eveline’s Senior Year: Musical Notes

Eveline’s Senior Year: Smallpox

Eveline’s Senior Year: What are you Serving?

Eveline’s Senior Year: Root Beer on the 4th

Eveline’s Senior Year: Miners, Miner and Maps